Class dismissed: Triumph of ‘Working Girl’ is as much about nostalgia as feminism

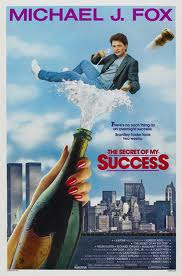

The corporate (and social) machinations should turn “Working Girl” into farce, but they don’t. It is curiously the same story as a movie from the prior year, “The Secret of My Success.” Which one of these films is more capable of a statement about feminism? That’s an interesting question.

In each, a young go-getter in Manhattan takes advantage of an empty office to spearhead a major Wall Street deal without anyone noticing. Roger Ebert gave “Secret” 1.5 stars, but “Working Girl” got 4, even though Ebert’s comment about the former (“Everyone in the movie is an idiot or the mystery would be solved in five minutes”) applies equally to the latter. One difference is that “Working Girl” is helmed by Mike Nichols, something of an auteur in this genre whose credits of working-women films around this time included “Silkwood,” “Heartburn” and “Postcards from the Edge.”

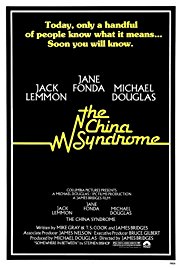

“Working Girl” was written by Kevin Wade. Either Wade or producer Doug Wick, depending on whose account you find most convincing, came up with the idea simply from seeing career women commuting in New York in sneakers while carrying heels. Wick in 2018 revealed, “A lot of directors said it was a TV movie.” One who liked it was James Bridges, who already had “The China Syndrome” and “The Paper Chase” under his belt. Bridges signed on, Demi Moore was going to be Tess, and the Katharine character was originally a man. Then Bridges dropped out, replaced by Nichols, and Sigoruney Weaver and Harrison Ford and Melanie Griffith came aboard. That “Working Girl” is the project of three males — and that a male actor is given top billing despite limited scenes — doesn’t preclude its potential for a feminist statement ... but what kind of statement is it? A young woman usurps a senior woman’s office, clothing, connections and eventually, man.

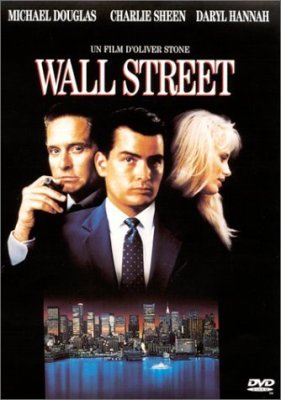

Ellen Goodman seemed to think the movie is an evaluation of feminism rather than assertion of it. She noted parallels to Oliver Stone’s “Wall Street” and “The Secret of My Success,” writing in January 1989 that “Working Girl” in a sense begins where “9 to 5” left off but ultimately illustrates disappointment of 1980s feminism, that “the daughters and sisters of the establishment look a lot like their fathers and brothers” and that, “For every woman who prefers working for a female there is another who feels she has gained nothing by the advancement of women except another layer of human beings over her head.”

Another 1989 article, titled “Drop-Dead Clothes Make the Working Woman,” by Constance Rosenblum in the New York Times, says “Working Girl” is a “much praised” film and that Weaver certainly looks great but that her character is “all style but little content” and that “in the real world,” her character would “probably last for about two minutes — reinforcing every stereotype about working women in the process.” Rather, “It’s Weaver’s male counterpart, the Harrison Ford character, who has the energy and finesse to cut the deals.”

A 2016 essay by Cameron Maitland, which argues that the movie is more about class and privilege than the glass ceiling, insists that Tess is “the perfect Reagan-era feminist,” while conceding the movie ignores women of color and depicts a promotion “unbelievable even by today’s standards.”

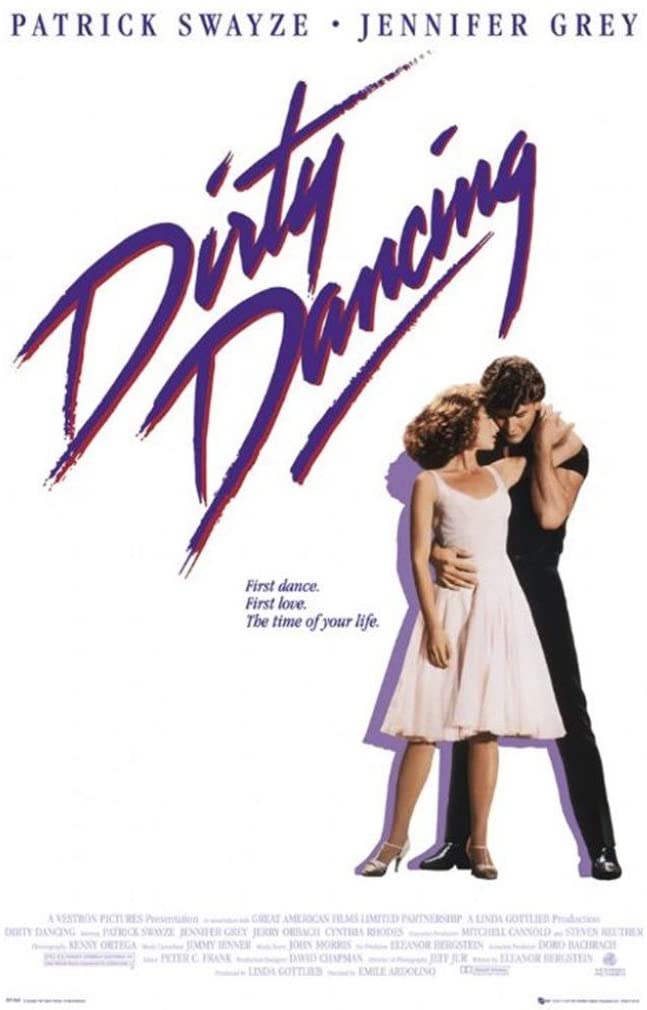

“Working Girl” in fact is not a triumph of feminism, but mainstream. The latter term is an endangered species. Movies like “Working Girl” remind us of how entertaining a tale for grownups — consumed in two hours at a theater, not in a three-week television “binge” — can be. “Mainstream” used to be a pejorative, a film with little edge, taking no chances while satisfying the masses. Now it’s a refreshing throwback to the times when “Rocky” and “Back to the Future” and “Dirty Dancing” and “Pretty Woman” could pack seats, and not those of living-room sofas. Today’s world of cinema is so algorithmically splintered, and flooded with marginal products aimed at marginal audiences, there’s no longer any such thing as “the movie everyone’s talking about.”

Griffith was sure she was right for Tess even if the film’s backers weren’t. “My story is Tess’ story,” she said in 2018. Casting chief Juliet Taylor says Griffith “was the girl” and the filmmakers loved Alec Baldwin as Jack Trainer, but the studio was “catatonic” about having “two unknowns” at the time in the lead roles. Wick said that Weaver and Ford were brought in for box-office heft, only to have Fox decide it didn’t want to pay for them, until it did, with Baldwin having “nailed” his new character despite an “awkward adjustment.” Nichols enlisted Wall Street help for Griffith from investment banker Liam Dalton, and “We had an incredible romance,” Griffith said. Weaver is said to have shadowed Elaine Garzarelli, who in the ’80s was a very prominent Wall Street name, a very prominent female name in a male-dominated world who could probably vouch for some of the harassment Tess receives in the film.

In these movies such as “Secret” and “Wall Street,” we see that getting ahead with business acumen is only partly about examining the balance sheet; the rest is about attending cocktail parties and figuring out the best times to sneak up on targets who don’t know they’re being watched and who can’t figure out on their own what deals are best for them. The skulduggery in “Secret” and “Wall Street” is more clever and imaginative and, for lack of a better word, believable than in “Working Girl,” in which crashing a wedding is somehow necessary for closing a deal.

“Working Girl” is fascinated with lingerie. What lifts the movie though is not underwear but the repartee between Griffith and Weaver. Their conversations are cringeworthy and delicious at the same time. “Who makes it happen?” (a question that will prove prophetic), and “Two-way street” and “bony ass” and “Oh my God, she’ll stop at nothing.” And the movie’s funniest line: “I’ll need help bathing and changing.” Katharine actually does offer quality advice on appearance and workplace politics. Tess has had several recent bosses and is down to her last chance. For a little while, we actually don’t know whether Katharine will prove a springboard or obstacle. She’s dicey as a mentor ... but, it turns out, ideal as a villain.

Weaver is playing perhaps the most condescending 29-year-old in a movie, though Weaver was actually in her late 30s at the time and frankly appears that way in the film. This is a problem for Nichols — what viewers are told (Katharine is 29) is different than what they see. And why are they told this? Because of a flaw in the script. Neither Tess’ nor Katharine’s age matters to this plot. But Wade evidently thought Tess needs extra motivation beyond the stifling and harassment and frustration at her previous jobs, so he decides she is so troubled by her lack of achievement by her 30th birthday that she might be inclined to do an end-around her boss. And even then, according to the script, she maybe wouldn’t do it ... except her boss is even younger. (Curiously, a completely unrelated film that was recently released, “tick, tick ... Boom!,” also deals with an obsession with 30th birthdays.)

There must be a world of difference between the work history of Tess and the work history of Katharine. Katharine probably attended an Ivy League school and has years of Wall Street work under her belt and speaks any number of foreign languages; Tess has “some night school” and works for temp agencies and is decidedly blue-collar. It’s a bit of a disservice that the movie never acknowledges that Katharine would possess important skills that Tess has not yet acquired. Nevertheless, “Working Girl” makes a beautiful point — that success isn’t about background and polish, but drive and ideas.

Betrayal sets in when Tess notices on Katharine’s computer that Katharine is, in fact, secretly pursuing Tess’ idea after telling Tess it wouldn’t work. It’s not a highly visual revelation, and the fact it’s detected on a dos computer of the mid-1980s dates the film, along with its hairstyles and fears of Japanese business takeovers. And careful what you wish for — the man whom Tess views as a prize was merely stringing Katharine along and not even spending time with her after a serious injury. Later, not realizing what has been happening, Katharine will try to explain why she was looking into Tess’ idea without giving her credit, relating an anecdote about the man in the middle that, unsatisfyingly, may or may not be true and raises questions about the ending, not to mention that the tepid love story(s) gives viewers no great yearning to see the two principals end up together.

Secretarial revenge apparently is potent box-office formula. “9 to 5” was the No. 2 hit for 1980; it grossed about $103 million worldwide, according to the Internet Movie Database, the same as “Working Girl” would eight years later, both highly profitable. The arc of feminism is apparent from the two films — by the end of “Working Girl,” the despised exec is a female, chores such as getting coffee and picking up the dry cleaning are frowned upon as work assignments, and the term “secretary” is just about verboten: “If it’s OK, I prefer assistant.”

That comment comes from a beautiful character seen only at the end of “Working Girl,” Alice Baxter, played by Amy Aquino. Alice and Tess engage in an uneasy but fascinating discovery as to who’s working for who. It’s ludicrous, of course, that Tess wouldn’t know she now has her own office, but the scene still overachieves, a gem. How many people, this very day, are meeting their new boss for the first time and feeling a little bit vulnerable while trying to size her or him up? Subordinates don’t want to say the wrong thing. Someone who finds herself/himself a boss for the first time doesn’t either. Aquino said in 2018 that Griffith invited her to her trailer for lunch, and “I just ate up her generosity of spirit.” We have every confidence that after a lopsided intro, Alice and Tess are going to click and do this the way it should be. Nichols soars here, leading into his provocative and much-discussed final shot of Tess being just one of many, many New York professionals.

“Working Girl” struck a nerve with the Oscars, receiving a flurry of elite nominations, for Best Picture (It lost to “Rain Man”), Best Director (Nichols lost to Barry Levinson, “Rain Man”), Best Actress (Griffith lost to Jodie Foster, “The Accused”), and actually two Best Supporting Actress nominees (a difficult feat), Weaver and Joan Cusack (who picks up where she left off in “Broadcast News”), who both lost to Geena Davis, “The Accidental Tourist.” The movie had one winner — Carly Simon for the exceptional original song “Let the River Run.”

Coincidentally, the competition between Weaver and Griffith wasn’t limited to the characters in the film. Weaver received her own Best Actress Oscar nomination for another movie, “Gorillas in the Mist,” competing against Griffith. That year marked the third Oscar nomination for Weaver, the first for Griffith. For whatever reason, those nominations stopped there.

“Working Girl” ends nearly like “The Secret of My Success.” A corporate deal is about to be struck, and then someone bursts in on the meeting with significant leverage to upend the process. Yet in “Secret,” the male protagonist is lifted over the top by two females just realizing their own potential. While “Secret” settles its takeover in the boardroom, “Working Girl” hastily defers the conclusion (too fast, before you really have time to feel sorry for Tess) to a chance elevator encounter shortly after in which Tess is suddenly able with a few soundbites to defend her role. That she accepted defeat so passively at such a high level goes against the grain of the rest of the movie, and it seems Wade and Nichols have gotten too cute here.

Katharine’s comeuppance. Does she deserve it? She has apparently lied and thwarted someone’s ambition for her own gain. Like Nathan Jessep in “A Few Good Men,” she is mostly guilty of underestimating the ability of a woman of lower rank to defeat her. But unlike Jessep, she is blindsided about being defeated until it is too late. She gets no chance to defend herself. We might even feel a little sorry for her, if she hadn’t been hitting on that doctor, a strange scene that doesn’t fit.

Will Tess be totally honest with her future colleagues as to how she landed this office? Griffith insisted to Gene Siskel in late 1988 that Tess would not be a “conformist” after the movie ends. “I think she continues her unique way of putting deals together. And I think she marries Jack and I think she has babies with him and that they have their own firm and become business partners. A nice honest life.”

We know that in the performance world, Hollywood sees a big difference in talent and skill; the New York Knights can’t win without Roy Hobbs in the lineup. As for big business, Hollywood is far more skeptical. Achieving that office is of serious importance to the officeholder. Is it really, as Nichols questions in his final shot, very important to the employer? Or is it that any of us could easily find ourselves in someone else’s shoes?

3.5 stars

(November 2021)

“Working Girl” (1988)

Starring

Harrison Ford

as Jack Trainer ♦

Sigourney Weaver

as Katharine Parker ♦

Melanie Griffith

as Tess McGill ♦

Alec Baldwin

as Mick Dugan ♦

Joan Cusack

as Cyn ♦

Philip Bosco

as Oren Trask ♦

Nora Dunn

as Ginny ♦

Oliver Platt

as Lutz ♦

James Lally

as Turkel ♦

Kevin Spacey

as Bob Speck ♦

Robert Easton

as Armbrister ♦

Olympia Dukakis

as Personnel Director ♦

Amy Aquino

as Alice Baxter ♦

Jeffrey Nordling

as Tim Rourke ♦

Elizabeth Whitcraft

as Doreen DiMucci ♦

Maggie Wagner

as Tess’s Birthday Party Friend ♦

Lou DiMaggio

as Tess’s Birthday Party Friend ♦

David Duchovny

as Tess’s Birthday Party Friend ♦

Georgienne Millen

as Tess’s Birthday Party Friend ♦

Caroline Aaron

as Petty Marsh Secretary ♦

Nancy Giles

as Petty Marsh Secretary ♦

Judy Milstein

as Petty Marsh Secretary ♦

Nicole Chevance

as Petty Marsh Secretary ♦

Kathleen Gray

as Petty Marsh Secretary ♦

Jane B. Harris

as Petty Marsh Secretary ♦

Sondra Hollander

as Petty Marsh Secretary ♦

Samantha Shane

as Petty Marsh Secretary ♦

Julia Silverman

as Petty Marsh Secretary ♦

Jim Babchak

as Jr. Executive ♦

Zach Grenier

as Jim ♦

Ralph Byers

as Dewey Stone Reception Guest ♦

Leslie Ayvazian

as Dewey Stone Reception Guest ♦

Steve Cody

as Cab Driver ♦

Paige Matthews

as Dewey Stone Receptionist ♦

Lee Dalton

as John Romano ♦

Barbara Garrick

as Phyllis Trask ♦

Madolin B. Archer

as Barbara Trask ♦

Etain O’Malley

as Hostess at Wedding ♦

Ricki Lake

as Bridesmaid ♦

Marceline A. Hugot

as Bitsy ♦

Tom Rooney

as Bridegroom ♦

Peter Duchin

as Trask Wedding Orchestra ♦

Maeve McGuire

as Trask Secretary ♦

Tim Carhart

as Tim Draper ♦

Lloyd Lindsay Young

as TV Weatherman ♦

F.X. Vitolo

as Bartender ♦

Lily Froehlich

as Clerk at Dry Cleaner’s ♦

R.M. Haley

as Heliport Attendant ♦

Mario T. DeFelice Jr.

as Helicopter Pilot ♦

Anthony Mancini Jr.

as Helicopter Pilot ♦

Suzanne Shepherd

as Trask Receptionist

Directed by: Mike Nichols

Written by: Kevin Wade

Producer: Douglas Wick

Executive producer: Robert Greenhut

Executive producer: Laurence Mark

Cinematography: Michael Ballhaus

Editing: Sam O’Steen

Casting: Juliet Taylor

Production design: Patrizia Von Brandenstein

Art direction: Doug Kraner

Set decoration: George DeTitta

Costumes: Ann Roth

Makeup and hair: J. Roy Helland, Alan D’Angerio, Joe Campayno

Production supervisor: Todd Arnow

Unit production manager: Robert Greenhut

Assistant unit production manager: Timothy M. Bourne

Stunts: Jim Dunn, Frank Ferrara, Natasha Buser, Philip G. Neilson, Michael C. Russo, Bronwen Thomas