‘The China Syndrome’ exposes the core of TV news clichés

“The China Syndrome” is not a takedown of nuclear power. It’s not even a takedown of TV newscasts. It’s a takedown of suits. Those who wear one are the bad guys, spoiling all the potential public benefits of their businesses with reckless greed. Their employees try to do the right thing, are denied, eventually can’t take it anymore and fight back. In most industries, the result would be what we call a “leak.” Here, we get a meltdown.

The whole thing might well have been a flop. Then real news intervened.

Jane Fonda says in DVD commentary (copyright 2004) that she was originally interested in pursuing the 1974 story of Karen Silkwood, a nuclear-facility worker who died in a mysterious car crash. Around that time, under the Columbia umbrella, Michael Douglas was also interested in the nuclear-plant concept and had been entertaining a script by Mike Gray. Douglas recruited Richard Dreyfuss to team with himself as a pair of documentary filmmakers. But suddenly hot as a young Oscar winner, Dreyfuss quit the project over a salary dispute. Fonda had to drop the Silkwood story (according to a 1979 New York Times article, she was “refused the rights by Miss Silkwood’s heirs”) and, with producing partner Bruce Gilbert, apparently was interested in both a nuclear-power story and a TV news story. Columbia said it was only doing one nuclear power film, so Fonda joined forces with Douglas, who retooled the Dreyfuss part into a female TV reporter.

The TV portion of “The China Syndrome,” which is about 25% of the movie and lacks depth and mostly just tosses around punch lines, seems mostly attributable to Gilbert. Fonda says Gilbert was interested in changes in the TV news business; he had been researching the evolution of news broadcasts and found that the format had become one of “happy talk,” usually involving a woman. Gilbert acknowledges “Syndrome” had multiple agendas. “This almost never works, to take two disparate stories and try to sew them together and make some kind of coherent whole. Um, in retrospect, I think now we see ... it worked,” Gilbert says. It did, but the commitment to dueling storylines prevents “The China Syndrome” from elevating into the realm of landmark films. It’s a pop-culture success.

Ultimately, “Silkwood” became a Mike Nichols project that reached screens in 1983, a decent movie snagged by legal concerns over identifying an actual company and mostly known for testing the pairing of Meryl Streep and Cher. “The China Syndrome” and “Silkwood” share several ingredients and are much the same grievance, a negligent corporate overlord that doesn’t care about nuclear safety. “The China Syndrome” puts this problem into the hands of sexy elites while “Silkwood” sees it through the eyes of the paycheck-to-paycheck everywoman. In each case, the revelations aren’t satisfying. What fuels the drama in each are the alarms — they get your full attention.

“The China Syndrome” introduces a beautiful conflict. Fonda, as the reporter Kimberly Wells, and Douglas, as Richard Adams, the acerbic “independent” cameraman, are on the premises of a nuclear facility for a light feature. A crisis appears to occur, and Richard defies the rules to take unauthorized footage. After rushing back to the TV studio, an intense, if unbelievably short, debate takes place over whether to air the footage. The boss, Jacovich (Peter Donat), has been summoned, and of course, he says no.

But actually, Jacovich is right. Kimberly and Richard haven’t done enough reporting. They haven’t gotten the plant’s response nor asked any experts what it means. What exactly was Kimberly going to explain with this footage? “Here’s what we shot today; we have no idea what happened, but sure was scary”?

Jacovich declares, “I’m not putting it on at 6. Not till I find out what’s going on. ... We don’t know exactly what it is; it’s totally irresponsible to go on the air without checking the facts.” That is sound news judgment. But then we transition from bona fide editorial decisions to Hollywood. Jacovich expresses no interest in the story, and we are led to believe that the threat of a lawsuit has bought off the station. News flash: News organizations are in the business of reporting things. That’s what they do. They hire lawyers too. It’s just not this easy to get a story killed.

Despite the makings of stimulating newsroom drama, “The China Syndrome” turns Channel 3’s coverage of this incident into a parody and insists on returning to the plant, identifying all the short cuts and greed and leaving our heroes to clean up the mess, which even includes treating severely wounded individuals while police and paramedics stand around. Soon, it’s clear that the suits fight dirty and are going to be tough to beat, especially on their home turf. But how susceptible is a nuclear plant to slick Hollywood drama?

Not very. An early demonstration of how the plant works by its PR frontman, Bill Gibson (James Hampton), is a valid try at Cliffs Notes on nuclear-power generation. But it’s still not easy to understand. Worse, it doesn’t explain at all why the two incidents that occur at the plant should be considered “incidents” if not much worse. There are so many terms thrown around, valves, relays, scrams, turbine trips, annunciators, pumps, wells, generators, 110% speed ... apparently some of the equipment is not fastened strongly enough to the walls. Roger Ebert, in a 4-star 1979 review, writes that the mishaps are based on “actual occurrences” at nuclear plants. That is also the opinion of the film’s consultants, a group of nuclear engineers who had resigned from General Electric; one told the New York Times, “Each aspect of the plot is based on documentable actual or potential events.” The Times also reported that “at no time did the filmmaker hire a consultant favorable to nuclear power.”

Within a week of the film’s release, The New York Times published a fascinating assessment of the film from six nuclear experts, some of them critics of the nuclear industry, others advocates. One of the latter was David Rossin, a Commonwealth Edison scientist in Chicago, who said the film’s opening crisis resembled a 1970 situation at a nuclear facility in Dresden, Ill. “Obviously, they used that event for the one in the film,” he told the Times, but, “There were enough obvious changes from what happened to make it an exciting story. If they had stuck to the facts, there wouldn’t have been [a] movie.” (He adds that he saw the film at a special Chicago screening attended by Jane Fonda, Jack Lemmon and Michael Douglas. The stars afterward conducted a Q&A with college journalists, and before Rossin had made any comments, he was asked to leave by a Columbia Pictures PR man.)

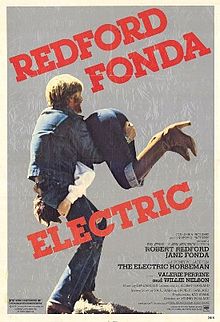

For viewers, the risk isn’t getting bombarded by radiation but by Hollywood’s TV news cliches. Roughly every 15 minutes, we need Kimberly assigned to something frivolous. She is commanded, “You’re better off doing the softer stuff.” Fonda demonstrates, as she does in “The Electric Horseman,” that film actors can be devastatingly good as TV reporters. As with “Network,” the filmmakers appear fascinated by TV studios, the multiple screens sitting around in which multiple images can be portrayed at the same time. Kimberly’s bosses and editors frequently comment on her hair and debate whether she should cut it. “We haven’t talked to her about it, but she’ll do what we tell her,” one male voice is heard to say. While no women appear to work at the nuke plant, at least KXLA employs more than one female, though none in management.

Notice “The China Syndrome” does not include any #MeToo moments. Males will condescend to Kimberly, but in this film, they will not harass her. Ah, but wait — in a deleted scene available in the DVD release, there is, in fact a #MeToo moment. Attending a party at Jacovich’s home, Kimberly encounters her drunken colleague/anchor, Pete Martin, poolside. Pete chortles, “I got it, you wanna play Cars? Cars, you know, honk honk!” Then he grabs Kimberly’s breasts, and she pushes him in the pool. Everyone laughs. Kimberly ends the incident by making a face to Jacovich. No one indicates interest in notifying HR. In 1979, there were real problems in the world, but as far as cinema is concerned, those problems did not include the unwanted or illegal touching of another person. The same is true for “Broadcast News” eight years later. Only in the 2010s did the world become aware of this monstrosity. Surely the folks with causes in 1979 never realized how innocent their grievances would one day look. Donat in DVD commentary says this was one of his favorite scenes, that Kimberly pushing Pete into the pool and stalking off was a “marvelous moment.” (Pete Martin, by the way, is played by Stan Bohrman, a veteran TV/radio newsman who won awards and appeared in one movie in his life: this one.)

The film’s third hero is the plant insider, Jack Godell, a spirited Jack Lemmon performance. His is the most demanding role. He must come across as a savvy, smart, reliable professional who, in the face of egregious greed in a very short period of time, commits a highly risky criminal act for the sake of preventing disaster, not dissimilar from Lemmon’s Oscar-winning turn in “Save the Tiger.” But even for a two-time Academy Award winner, the holes in “Syndrome” are too much. A couple of times, Jack orders his staff to go against the book, such as “Open 14 and 15,” something they declare is not permitted; “You can’t do that, Jack.” These decisions appear to pay off, suggesting Jack’s panicked improvising is more trustworthy than U.S. regulations. Or was he just lucky? Why was he only looking at the broken water-level gauge and not the one that was working? Can this fellow be considered competent? What did Jack think of plant ownership before the opening scenes? He seems to have a good job; what does he do when there’s no crisis? He converts from responsible defender of nuclear power to gun-wielding lunatic virtually overnight. Just as the plant is undergoing a critical restart, it appears as though Jack isn’t even scheduled to work that day. When he arrives, agitated, his underlings suggest he go home and relax, as though they weren’t expecting him.

According to Director James Bridges’ partner Jack Larson, Lemmon apparently was angry upon seeing what was cut from the completed film and vowed not to do any publicity for it. But, Larson said, “Jack came around ... and never mentioned this again.”

The timeframe is also a hole deep enough perhaps to reach China. According to the movie, a marathon NRC hearing takes place within a day or two of the accident, yet the news media (including in-the-know-but-tight-lipped KXLA) report nothing on the incident. In less than a week, it seems, the plant is restarted, without any inspections from any authorities or even corporate individuals from outside that particular plant.

Security seems to be lax across the board. Here you have a man with a gun at a nuke facility, and police are not even called or allowed in. An independent contract employee who has stolen film that technically belongs to the TV station is allowed to come and go as he pleases at the station. A hit squad from a national engineering firm that seems straight out of “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” (“they’ve got their own security men”) can be summoned at a moment’s notice to trail not only Jack Godell but his contact (that’s straight from the Karen Silkwood story), and California Highway Patrol is nowhere to be found. They can even push a car off a cliff, stop their own car on the cliff, make their way down the cliff, remove something from the damaged car, then go back up the cliff to their own car and drive away, without anyone noticing. Gilbert says in DVD commentary that the moviemakers were given a day to use a stretch of highway that was about to open to the public but hadn’t opened yet. By the way, what exactly were the thugs in suits going to accomplish by driving next to Jack’s car? If they were going to go to this much trouble to kill him, wouldn’t it make more sense to do it at his home?

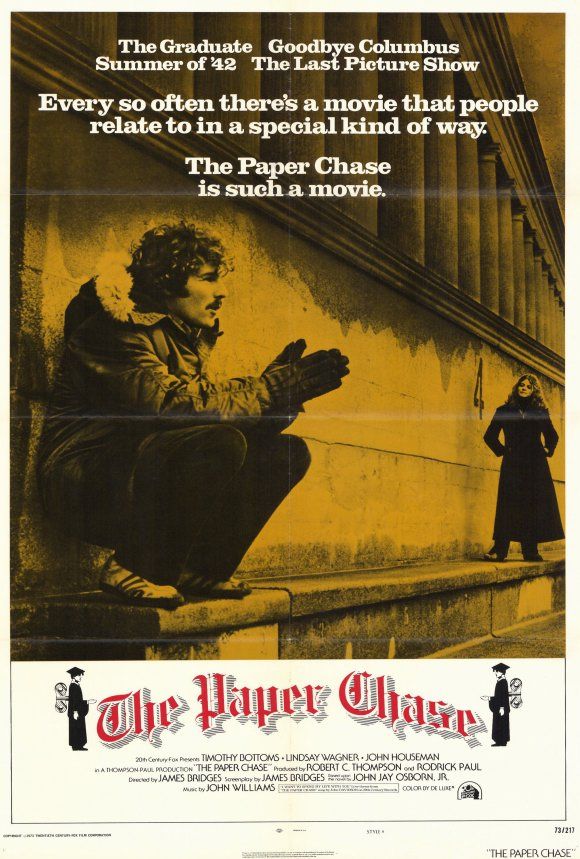

Shortcomings aside, “The China Syndrome” is highly watchable because of its stars and the crisp direction of Bridges. He finds interesting places to film. Bridges somehow has only eight directorial credits and a skimpy Wikipedia page despite catching fire three times, for this film, “Urban Cowboy” and “The Paper Chase.” All three are pop-culture gold. What do they have in common? That’s a good question. Bridges keeps a snappy pace but lets stardom flourish. He unleashed John Houseman, John Travolta and Debra Winger in the other two films, and Fonda carries “The China Syndrome.” Oddly enough, Fonda said in 1979 that Bridges “was scared of working with stars.” Douglas holds his own as Richard, the type of person every news veteran knows. But Douglas doesn’t get enough to do, and it’s Fonda’s film. She is “simply superb,” according to Ebert, and “keeps getting better and better,” according to Vincent Canby, who found the film “smashingly effective.”

Fonda and Lemmon received Oscar nominations. She lost to Sally Field in “Norma Rae.” He lost to Dustin Hoffman in “Kramer vs. Kramer.” “Syndrome” also was nominated for original screenplay (Mike Gray, T.S. Cook and James Bridges), losing to “Breaking Away,” and art direction-set decoration (George Jenkins, who was demanded by Bridges despite his price being beyond the budget, and Arthur Jeph Parker), losing to “All That Jazz.”

Besides its stars, other characters are used expertly by Bridges. A bartender and his customers recognize Kimberly. The way they act around her shows why Kimberly’s fame is a mixed bag. The ages and clothing of Jack’s plant crew suggest an unsophisticated work force, people who may be diligent but not nearly as well-trained or as well-educated as people in these positions should be. The best line in the film comes from a supporting character, Wilford Brimley’s Ted Spindler. He is asked by Jack, “What makes you think they’re looking for a scapegoat?,” and replies, “Tradition.”

Probably contrary to his intent, Bridges depicts Bill Gibson, the tour guide/PR guy, as the most impressive employee at the plant. Gibson patiently explains how a plant works, he’s enthusiastic, and most importantly, unlike anyone else there, he actually follows the safety rules. They happily give the crew remarkable access. Gibson unfortunately, like James Karen as TV station boss Mac Churchill (in which he echoes his “Wall Street” persona), falls in the crevice that’s somewhere between perpetrator and victim in this film.

Bridges understands that Southern California is a beautiful place to film. His overhead shots of highways (always with remarkably light traffic) and mountains illustrate the natural beauty that a slipshod nuclear facility is encroaching upon. In the beginning, we see Kimberly, Richard and Hector on the freeway, sharing what looks like a jug of apple juice. These are rising professionals, not yet wealthy, beautiful potential out here, taking life as it comes. But it’s a reach to call “Syndrome” a coming-of-age story. Fonda was 42 when this picture was released, Douglas 35, Lemmon 54.

Perhaps the movie’s best scene is when Richard has brought the plant footage to a pair of nuclear experts. The two describe what they’re seeing in English. The first expert resembles Daniel Ellsberg. He suggests the plant crew came close to exposing the core. The second expert is played Donald Hotton, who despite being a sympathetic character must scare us, and his face does, as he explains what happens when the core is exposed.

Unfortunately, these experts’ interest in this very serious situation takes a lunch break. Instead of announcing at this public hearing what they have just seen, they keep it to themselves, waiting instead to receive some X-rays that A) they couldn’t possibly digest in time to make a coherent presentation and B) wouldn’t reveal anything anyway except the plant is overdue for some inspections. Bridges does not want these characters interfering with his heroes, so they’re left to mingle with the 100 or so folks at the plant hearing, as the movie decides to introduce tangential issues such as nuclear waste disposal.

Perhaps to its credit, and perhaps to its detriment, there is utterly no romance in “The China Syndrome.” Kimberly and Jack live alone. Neither appears to have a significant other. In a reach to make Kimberly lightly radical, her pet is not a kitty but a gigantic turtle. This is a gamble by Fonda that looks silly, as though Kimberly really does belong at the zoo. She could presumably date Richard, but he’s not in her league in terms of conformity. Kimberly and Richard, on this particular project, are united — report this big story. But they never emotionally connect. The same year, Fonda would play a TV reporter in “The Electric Horseman,” where circumstances will also temporarily align her with Robert Redford’s Sonny Steele, like Richard, a person with which she has a wonderful present but no future.

Is “The China Syndrome” unfair to nuclear power? Not exactly. Godell points out to Kimberly that 10% of her electricity is supplied by his plant. Not pointed out is that nuclear power is free of carbon emissions that, within a couple decades of the film, would be blamed for global warming. The film walks a shaky tightrope to avoid condemning the nuclear industry and feels significantly to the right of its stars and producers on this subject. Its wobbly message is that nuclear engineering is perhaps permissible but too risky to be left in the hands of businesspeople. Fonda said in 1979 (and emphasizes on the DVD), “The movie’s intended as an attack on greed, not on nuclear energy.”

Accidents indeed do happen. None could’ve been more timely than that of Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island. Two weeks after “The China Syndrome” premiered, a reactor partially melted down, in part because of a stuck valve, the most significant accident in the history of American commercial nuclear power. Never before or since has a movie proved such an effective “Told you so.” Fonda in DVD commentary insists the box office got a jolt, that people went to see the film to understand what happened, but Douglas, in the same commentary, actually says the opposite, that “it actually kind of hurt the movie,” because people saw all the news coverage and “thought they had seen the movie already.” Either way, the term “China Syndrome,” though illogical on multiple levels, garnered for a time the same kind of presence as “acid rain” or “killer bees.”

But no one blamed the press for Three Mile Island. Gilbert overreached. The real goats are at the power plant, not the KXLA newsroom. “The China Syndrome” determines that the offenses committed by nuclear operators are no worse than the concealing of them by the news media. Kimberly mentions “Woodward and Bernstein” 48 minutes into the film. But just five years after Watergate, that type of respect is yesterday’s news.

3.5 stars

(December 2018)

“The China Syndrome” (1979)

Starring: Jane Fonda

as Kimberly Wells

♦

Jack Lemmon

as Jack Godell

♦

Michael Douglas

as Richard Adams

♦

Scott Brady

as Herman De Young

♦

James Hampton

as Bill Gibson

♦

Peter Donat

as Don Jacovich

♦

Wilford Brimley

as Ted Spindler

♦

Richard Herd

as Evan McCormack

♦

Daniel Valdez

as Hector Salas

♦

Stan Bohrman

as Pete Martin

♦

James Karen

as Mac Churchill

♦

Michael Alaimo

as Greg Minor

♦

Donald Hotton

as Dr. Lowell

♦

Khalilah Ali

as Marge

♦

Paul Larson

as D.B. Royce

♦

Ron Lombard

as Barney

♦

Tom Eure

as Tommy

♦

Nick Pellegrino

as Borden

♦

Daniel Lewk

as Donny

♦

Allan Chinn

as Holt

♦

Martin Fiscoe

as Control Guard

♦

Alan Kaul

as TV Director

♦

Michael Mann

as TV Consultant

♦

David Eisenbise

as Technical Director

♦

Frank Cavestani

as News Reporter

♦

Reuben Collins

as Sportscaster

♦

E. Hampton Beagle

as Mort

♦

David Pfeiffer

as David

♦

Lewis Arquette

as Hatcher

♦

Dennis McMullen

as Robertson

♦

Rita Taggart

as Rita Jacovich

♦

James Hall

as Harmon

♦

Carol Helvey

as Waitress

♦

Trudy Lane

as Alma Spindler

♦

Jack Smith Jr.

as Tom

♦

David Arnsen

as KXLA Cameraman

♦

Betty Harford

as Woman at Demonstration

♦

Donald Bishop

as Hearings Chairman

♦

Al Baietti

as Pro-Nuclear Witness

♦

Diandra Morrell

as Sasha

♦

Darrell Larson

as Young Demonstrator

♦

Roger Pancake

as Gate Guard

♦

Joe Lowry

as Security Agent

♦

Harry M. Williams

as Fire Rescue

♦

Dennis Barker

as Jaws of Life

♦

Joseph Garcia

as Highway Patrolman

♦

James Kline

as Jim

♦

Alan Beckwith

as Technician

♦

Clay Hodges

as SWAT Squad Leader

♦

Val Clenard

as Val Clenard

Directed by: James Bridges

Written by: Mike Gray

Written by: T.S. Cook

Written by: James Bridges

Producer: Michael Douglas

Executive producer: Bruce Gilbert

Associate producer: Penny McCarthy

Associate producer: James Nelson

Associate producer: Jack Smith Jr.

Cinematography: James Crabe

Editor: David Rawlins

Production design: George Jenkins

Set decoration: Arthur Jeph Parker

Casting: Sally Dennison

Costumes: Donfeld

Makeup and hair: Bernadine Anderson (Jane Fonda makeup), Kaye Pownall, Don Schoenfeld

Unit production manager: James Nelson

Stunt coordinator: Bobby Harris, Carey Loftin

Stunts: Jerry Summers, Hill Farnsworth, Richard R. Drown