Our past catches up with us

— unless we outrun it —

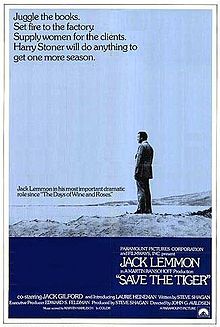

in ‘Save the Tiger’

At least two crimes are being committed in “Save the Tiger.” Both, it turns out, could lead to death. Even when professionals are enlisted to do them.

Just making these offenses happen, according to Steve Shagan’s script, is a victory. Justified by, of all things, previous wrongdoing.

Actually, they’re justified by more than that. Harry Stoner didn’t dig his own hole. Life dug it for him. And not for the first time. It’s his obligation to crawl out of it, for his band of brothers as much as himself.

What is the villain in “Tiger”? Time? Luck? The system? No, it is merely the world. “Tiger” is the timeless story of disenchantment with life, a yearning for the past when everything seemed simpler and sacrifices were made for a seemingly better future that only gets worse by the day.

“Tiger,” a spectacular portrait of early 1970s Los Angeles written by Shagan and directed by John G. Avildsen and fronted by Jack Lemmon, is an extension of “Patton.” It would be relevant at any time, never moreso than at the cresting of the Vietnam Era. Lemmon’s Harry Stoner may as well have served under Patton. Harry leads a wealthy lifestyle, but he knows all too well that glory is fleeting. Three decades after making the other side’s son of a bitch die for his country, Harry doesn’t experience glory, but nightmares. His war is long over; now he’s only got the daily battle of making a living. He can’t help but wonder if his fallen band of brothers would be unimpressed if they could see him now.

Lemmon got the Oscar; cinematographer Jim Crabe, despite a landmark effort, didn’t even get a nomination. The two draw beautiful contrasts with paradise. The mountains of Malibu tainted by smog; the beach figuratively soaked with the blood of soldiers. Crabe’s sidewalk scenes, especially the one at the top of this page, ignite the potential of Southern California with a spectacular, colorful fuse. This is a quiet, powerful yearning ... if only we could live without our baggage.

“Tiger” was written as a movie. It could more than hold its own as a play. But that would be dismissing its staggering imagery of gorgeous and vulnerable Los Angeles.

There is a strong suggestion in “Tiger” that capitalism doesn’t work, at least not efficiently. Capri Casuals has a skilled, dedicated work force and an outstanding new product. Surely the operation is going gangbusters. No, it’s going bankrupt, for reasons never explained. Perhaps because this is an outdated business model best suited for the 1940s, or perhaps simply because the country is in the “crapper.” Roger Ebert, in his 1973 review, suggests Shagan “tried too hard to find a place in his script for everything on his mind.”

“Tiger” contains a lot of references to random events. Harry’s train of thought extends from the 1940s Brooklyn Dodgers to the Kennedys and James Earl Ray. Was Shagan overreaching? Yes. But when characters feel the deck is stacked against them, this is how they think.

Is “Tiger” about aging? Harry doesn’t have the typical physical problems of such a plot. There’s a blatant suggestion of a generation gap with a young woman, but in terms of judging fashion — forever a young person’s business — Harry can more than hold his own with Rico, his star designer. There is a cinematic crutch in their conversation; Rico’s backstory would not be rehashed in real life, but viewers need to know the history. The script could be more ambitious here. But Avildsen brilliantly brings Rico back to Harry’s office for a quick affirmation of the belt, a sensational scene bolstering not only Harry’s credentials but Rico’s respect for those credentials and their ability to succeed as a team. Similar exchanges occur with William Hansen’s remarkably authentic Meyer, the aging pattern cutter said to be the best in the business. Shagan and Avildsen say Hansen had no experience with a sewing machine before landing the part.

The film certainly represents the slippery slope of wrongdoing. It can be inferred, coincidentally just before Watergate came to light, that small crimes only lead to larger crimes. Harry is so cynical, he sees little distinction. “Arson or fraud, it is the same accommodations,” he declares. There’s no other way to stay afloat; hard work and skill are mostly irrelevant.

The notion of antihero probably peaked in 1973, the year “Tiger” was released, when “The Brady Bunch” aired an episode depicting Bobby idolizing Jesse James. “Bonnie & Clyde” and Clint Eastwood’s Westerns had already pushed the envelope. Those works and “The Godfather” proved that criminals and renegades could thrive as movie heroes provided their actions could be faintly attributed to self-defense. It’s not something human beings like to admit: Many bad guys are actually popular. In 1977, people wore Darth Vader Halloween masks, and in 1987, stock traders cheered Gordon Gekko. This very powerful artistic concept is the enabler of “Save the Tiger.”

For Harry, and his likable business partner Phil (played by Jack Gilford in an Oscar-nominated turn), crime is not about greed; it’s that the alternative is much worse. Especially for Harry, who, at a household cost of $200 a day, is extended. He might be looking for work around age 50. Bankruptcy. There are dozens of people employed by this company. If it fails, they’re on the street. Harry argues that if they made missiles, “Congress would send us a certified check,” but they make dresses. Harry will reveal that his goal is quite modest: one more season. If he succeeds, what will he do two seasons from now? Will there be other revenue sources to exploit? We have to think he’ll get by.

Avildsen in the director’s commentary refers to Harry as an “unsung hero” of society who meets a payroll.

One implication of “Tiger” is that when you have seen the horror of war, crime is small potatoes. Notice the shrugs whenever illegality is mentioned. Law enforcement is nonexistent, making Harry’s half-hearted cloak-and-dagger routine comical. Harry’s wife hardly seems alarmed to learn about the “ballet with the books.” Harry and Phil enjoy a nice lunch despite the criminal activity they’ve discussed during the morning. There’s yet another implication about the wrongdoing — maybe it’s kind of fun. Harry’s life is static. Maybe beating the system gives him a charge.

Harry Stoner is too familiar with difficult choices. He learned early in life, in an assignment that should be asked of no one but was asked of countless people of his generation (and also of the 1970s generation he struggles to connect with), to appreciate the ability to survive; worry about the consequences later.

Lemmon was born in 1925. Is it possible he experienced some of the battlefield images that plague Harry? Born into privilege, Lemmon was educated at Rivers Country Day School and Phillips Andover Academy. He entered Harvard in 1943. Standard online biographies make no mention of his draft situation. According to a New York Times obituary, “Despite low marks in the Reserve Officers Training Corps at Harvard, he was commissioned as an ensign during the last days of World War II and spent seven months in the Navy without seeing action.”

Steve Shagan was born in 1927. His Wikipedia page, citing a book, says he joined the Coast Guard when World War II “broke out” (though he would've only been 14 at the time of Pearl Harbor) and began writing to pass the time. Shagan died Nov. 30, 2015, in Los Angeles. His family-paid death notice makes no mention of his service but, in a nod to the film’s title, indicates memorial donations may be made to the World Wildlife Fund.

Shagan says in the director’s commentary on DVD, likely done in the early 2000s and after Lemmon passed away, that the motivation for the script was “anger,” that no other movie to that time referred to the coffins returning from Vietnam and also that his WWII generation was “forgotten” by a country that was neglecting “the middle guy in society.” This explains why Lemmon’s character is sympathizing with the Vietnam generation and not scolding it for its resistance.

Shagan’s screenplay received an Oscar nomination in the “original” category; officially “Best Writing, Story and Screenplay Based on Factual Material or Material Not Previously Published or Produced.” His death notice says the screenplay was “based upon his novel of the same name.” But his obituary in The Hollywood Reporter suggests the reverse: “Lemmon prodded Shagan, who also produced the movie, to make a novel out of his screenplay.”

This can be chicken-and-egg science: For comparison, Mario Puzo (with Francis Ford Coppola) a year earlier was awarded the best adapted screenplay Oscar for “The Godfather,” purchased by Paramount as an unfinished novel in 1967.

Shagan’s script backs Harry without blinking. There is horror in the world. You can’t ignore it, but must confront it. “By any means necessary” would’ve been an apt title. Wishing for ideals doesn’t make them happen. The world is so screwed up, survival depends on cutting as many corners as one can get away with.

“Tiger” opens with a tune that sounds hauntingly like the theme from “Chinatown,” which emerged a year later. Shagan says in DVD commentary that “Tiger” begins with a trumpeter playing “I Can’t Get Started.” Avildsen says it was supposed to be “Mack the Knife,” but Shagan says, “We couldn’t get it.”

Images begin with a foggy shot from Mulholland Drive. We see the outline of Harry’s pricey home, then the warehouse district of Los Angeles, then the mountains of Malibu, and the beach. He and his wife, Janet, live a comfortable life in Beverly Hills, served breakfast in bed by a maid. But something’s wrong. Harry awakes in a cold sweat, suffering from PTSD. These bedroom scenes are not glamorous: taking a shower, shaving, putting on underwear, blowing a nose.

Prior to about, oh, the late 1960s, movies rarely showed people in underwear. Since the early ’70s, that often has been deemed a necessary way of illustrating a character that viewers — but not most of the other characters — are aware of. This is a rare flaw in “Tiger.” Harry’s bedroom soliloquy is too long. We can adequately guess how he looks in underwear and don’t much care.

The extended dialogue includes a misstep on the part of Avildsen. Noting in the director’s commentary that he was well aware of Lemmon’s propensity to overact, he lets it happen when Lemmon depicts the windup of Johnny Vander Meer. Early in the film, this scene hints that “Tiger” will be another vehicle of Lemmon’s shtick typically best suited for comedy.

Avildsen was hardly the only director wary of this. In a 2004 interview with the DVD of “The China Syndrome,” a later Lemmon film, the partner of that film’s director, James Bridges, says, “Jim and Jack had an agreement that Jack Lemmon was not going to be too Jack Lemmon. He was not going to do absolutely what Jack Lemmon always did. ... So then Jim would say after a take, Jack, it’s too Lemmony, it’s just too Lemmony.”

Baseball is Harry’s connection to a better world. He had a good arm, and he laments the game isn’t played the way it used to be. “The pitchers don’t wind up anymore” is somehow a chief complaint. But he doesn’t even go to the games anymore. “They play on plastic.”

The scattershot bedroom conversation indicates the couple are not having the best day. There is condemnation of a dead man, Janet’s Uncle Bernie, whose funeral she must attend. “What a bastard,” she says. “Screwed everybody,” Harry agrees.

Harry observes a news story about the death of the Pacific World whale Kamu, a fighter who had been “swimming against the current for three years.” Janet notes a man shot for no reason walking out of Mario’s restaurant.

Their daughter, Audrey, has been shipped overseas. “She’s better off in Switzerland,” Janet insists.

Some of the conversation involves Janet’s suggestion Harry see a doctor about his nightmares. He jokes that it’s merely “repressed sex” or even Willie, the cranky car parker we will soon encounter. She also notes that marks on his back, which we later learn came from World War II, are getting worse.

Janet is aware of Harry’s problems. She wants him to see Dr. Frankfurter for some kind of “hypnosis.” That seems more of a ’70s thing than a ’40s thing, so Harry scoffs.

She tells him in the bathroom, “You’re worried.” And she says of Phil, “He’s always worried.”

Harry nevertheless is confident. He calls himself “Cuban Pete” a few times, apparently a reference to the 1946 film.

Harry picks up the flower child, Myra, on his way to work. This is hardly the only film that shows a man picking up a female flower-child hitchhiker. But Harry’s multiple interactions with Myra resonate curiously with a sequence decades later in Quentin Tarantino’s 2019 blending of real-life and fantasy in “Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood.” Myra, unlike Tarantino’s character, is the real deal, at least in terms of a real-life grooming situation (see below).

Why does Harry pick her up? Does he think she will understand something about him that his wife doesn’t? The best answer is that Harry is demonstrating 1940s chivalry; if someone needed a ride, you gave him or her one.

This scene needs to happen to justify why he will pick her up at the end of the day. A fairly clumsy exchange establishes their lingo divide, Myra mentioning “ball” and for some reason not really getting Harry’s suggestion to “Have a nice day.”

It’s clear upon Harry’s arrival at the factory that Harry has already decided what must be done to save the company. He just needs Phil to confirm what Harry is expecting the banks to say. Phil does so, and the arson plan is kicked into motion. Gilford, as the perfect straight man, makes a series of devastating facial gestures that express resistance, disapproval, resignation and sadness. We want to think Phil can sway Harry, but we even notice Harry grinning as he makes a call to Charlie. Harry’s regrets about criminality disappeared in the wind long before this day arrived.

In a beautiful subset of human drama, we see how Harry is pinched by a key buyer, Fred Mirrell, an aging Ohio businessman whose wife is “a sick woman” and “all scarred up.”

Fred is tortured enough to be counting the days. “I spent 5,362 nights with a sick woman,” he says, and the precision of that number totaling more than a decade feels legit.

Mirrell’s money is critical to Harry’s survival. Unfortunately for Harry, Mirrell sees his Los Angeles trip not about buying great clothing but good sex. He wants Harry to do something Mirrell can’t bring himself to do, which is immediately call Margo, whom Mirrell remembers quite fondly. Does Mirrell do this all the time? He might. But his painful rationalization suggests this is the one trip of the year, or season, he really cares about.

We learn Mirrell’s demand is far from unusual at this event, and that Margo isn’t exactly eager for this client. Mirrell is high maintenance and besides, all the buyers are in town, Margo says, and “I’m booked.”

Eventually, everyone pays for those 5,362 days. “He’s not a man, he’s a casualty,” Harry says of Freddie.

The script could do better in revealing how Harry prompts Margo to make this accommodation. We’re led to believe it’s force of will. We will also see them sit down together afterwards, and it seems clear that Harry and Margo go back a ways (including on a personal level) and have handled these kinds of situations before. Lemmon threads the needle — Margo seems more like a necessary business alliance, not a rich guy’s indulgence.

They commiserate over a drink in the spectacularly old-school hotel tavern, where the bartender efficiently serves drinks in sharp yellow jacket and black tie.

Harry tells Margo, “We both sell the same thing ... imagination.”

Prostitution, arson and imitation are the implied staples of the industry. Someone named Beckman had a successful fire a year earlier. Harry’s star designer declares “everybody copies,” and Harry agrees. “Save the Tiger” draws a faint parallel to “The Sweet Smell of Success,” the disturbing but brilliantly made unearthing of the reality of gossip columns. Think of the stress of trying to create trendsetting fashion lines knowing that buyers are just as interested, if not more, in one’s skills as a pimp. Harry doesn’t need a nightly dose of schemes to make a living. He just needs them occasionally, as in right now, when the clock is running out on his business.

Harry’s gray suit proves a striking motif. Several characters compliment it. It resonates a certain authority bolstered by his interaction with Rico. Lined in red and of Italian silk, this suit is notably similar to what Michael Corleone wears a year later in “The Godfather, Part II” while Senator Geary confronts him at the Corleone compound.

“Save the Tiger,” like “Norma Rae,” involves considerable footage in a clothing factory. But Harry is the polar opposite of Norma Rae. He is not rebelling against anything but fighting to save a status quo that is slipping out of his grasp. The company’s problem is critical to explaining Harry’s actions. It is described in pieces. The shortfall seems low enough that drastic action wouldn’t be needed. Today is order day. A bank that they’ve been doing business with for 15 years will only give them 50 percent of their orders in cash — so if they can write $300,000 in orders, the bank will lend $150,000 to get the line out. But they will still need another $142,000 in 60 days. This is difficult to show. The script relies on dialogue and specifically, a few testy arguments between Harry and Phil. Lemmon and Gilpin are so good together, we want to see them arguing all the time. They are not so much business partners as worthy adversaries.

Phil insists, “There’s a line I will not cross.” Legally he will; in spirit he won’t.

Phil suggests that the unions or textile mills will carry the company if necessary, but Harry says they refused to do so last year. Harry’s got a home in Beverly Hills. Perhaps he could take a second mortgage? Between them, it seems they could come up with ways to raise another $142,000 without committing a serious crime or enlisting the mob. Many people have an interest in Harry staying in business. Here we have a profound split with “It’s a Wonderful Life” — “Tiger” is not about to let anyone in 1973 take up a collection for Capri Casuals.

Harry’s world snaps at him in ways we all experience, a permanent Hollywood theme perhaps best illustrated in Michael Douglas’ “Falling Down.” Harry’s parking-lot attendant has a ridiculously short fuse. A cabbie interprets simple rounding as a slight. A ticket-taker is content to take her time. Is there any reason why Harry is receiving such caustic service? There can be only one — the country’s in the “crapper.”

Harry can at least tell Phil the one wonderful thing about L.A. is that it’s not Buffalo. Phil chuckles and says he falls for that all the time.

The stress of Harry’s day engulfs him at the podium of the Capri Casuals show at the Belgrave Hotel. As spectacularly haunting images of skeptical fallen soldiers stare at him, he reveals that he named his company after his Italian lifeline. “Capri has a, has a very special significance for me because I was recuperating there you see. I- it- it was a sanctuary for the living. ... It was filled with men, brave men, that stuck together because they believed in something,” Harry tells the gathering. His fashion show is a much different kind of war, and he’s far from done with the first.

Barely avoiding a meltdown, Harry must move on to the showdown with the hired arsonist, Charlie Robbins. Charlie is notably knowledgeable, fair and discreet. He has clearly heard about these kinds of problems many times. For whatever reason, Charlie thinks that three men discussing a serious crime will not distract other viewers of an adult movie. Perhaps this location is chosen because it among all the locations of the film somehow upholds a certain character. People in the theater are all in suits in apparent reverence for the outlet this endeavor provides.

What’s going to happen when Charlie torches the plant? Margo’s fiasco seems to suggest Harry has pushed his luck too far. But maybe, after his speech breakdown, he is just hitting his stride, like Tim Robbins in “The Player.” We would want to see Harry the next morning wave Charlie off and come up with a better solution. “We’ve rethought this; let’s not do it.” Instead there is a greater confidence that the Charlie plan, unlike the Margo plan, will not go awry.

Harry’s second encounter with Laurie Heineman’s Myra should be a total bust. “I’m house-sitting at the beach,” she conveniently points out. They trade pop culture references to further illustrate their steep generational divide. He calls pot “gage;” she thinks “we never fought a war with Italy.” But Heineman seals the scene with her eyes and expression. She senses that while this person is just another passerby in her life, he is burdened by extraordinary pain that only begins to explain why he’s here. (Avildsen in the director’s commentary says Heineman refused to compromise on a certain non-grooming belief popular at the time that he felt would be too much for viewers. The solution was to hand her a robe for these scenes.)

Those born around the time of “Tiger” likely remember Lemmon more as a staple of celebrity pro-am golf than a cutting-edge actor. Yet his post-“Tiger” resume would be the envy of many. Years later, he nearly matched this performance in another beleaguered Southern California workplace in “The China Syndrome,” though that film fails him in its final moments with its cartoonish conclusion.

“Save the Tiger” is rarely found on cable. Had Lemmon not captured an Oscar, it might well be forgotten. In an incredibly competitive decade for that particular award, he beat one of history’s most staggering lineups: Brando, Pacino, Nicholson, Redford.

Gilford deserved an Oscar also and in many years would’ve won; he lost to John Houseman. Shagan lost to David S. Ward of “The Sting.”

The slight is to Crabe, whose pictures are the bookend to Harry’s story.

In his acceptance speech, Lemmon noted previous criticisms of the award (when George C. Scott refused it and Brando made a mockery of proceedings by sending up a Latina actress with a fake name to accept his) and indicated Academy members should have no regrets.

“It is one hell of an honor, and I am thrilled.”

4 stars

(December 2015)

(Updated July 2019)

“Save the Tiger” (1973)

Starring Jack Lemmon as

Harry Stoner ♦

Jack Gilford as Phil Greene ♦

Laurie Heineman as Myra ♦

Norman Burton as

Fred Mirrell ♦

Patricia Smith as

Janet Stoner ♦

Thayer David as

Charlie Robbins ♦

William Hansen as

Meyer ♦

Harvey Jason as

Rico ♦

Liv Von Linden as

Ula ♦

Lara Parker as

Margo ♦

Eloise Hardt as

Jackie ♦

Janina as

Dusty ♦

Ned Glass as

Sid Fivush ♦

Pearl Shear as

Cashier ♦

Biff Elliott as

Tiger Petitioner ♦

Ben Freedman as

Taxi Driver ♦

Madeline Lee as

Receptionist

Directed by: John G. Avildsen

Written by: Steve Shagan

Producer: Steve Shagan

Producer: Martin Ransohoff

Executive producer: Edward Feldman

Music: Marvin Hamlisch

Cinematography: Jim Crabe

Editing: David Bretherton

Casting: Caro Jones

Art direction: Jack Collis

Set decoration: Ray Molyneaux

Makeup: Harry Ray

Production manager: Frank Baur