Confounding the experts,

‘Dirty Dancing’ still having

the time of its life

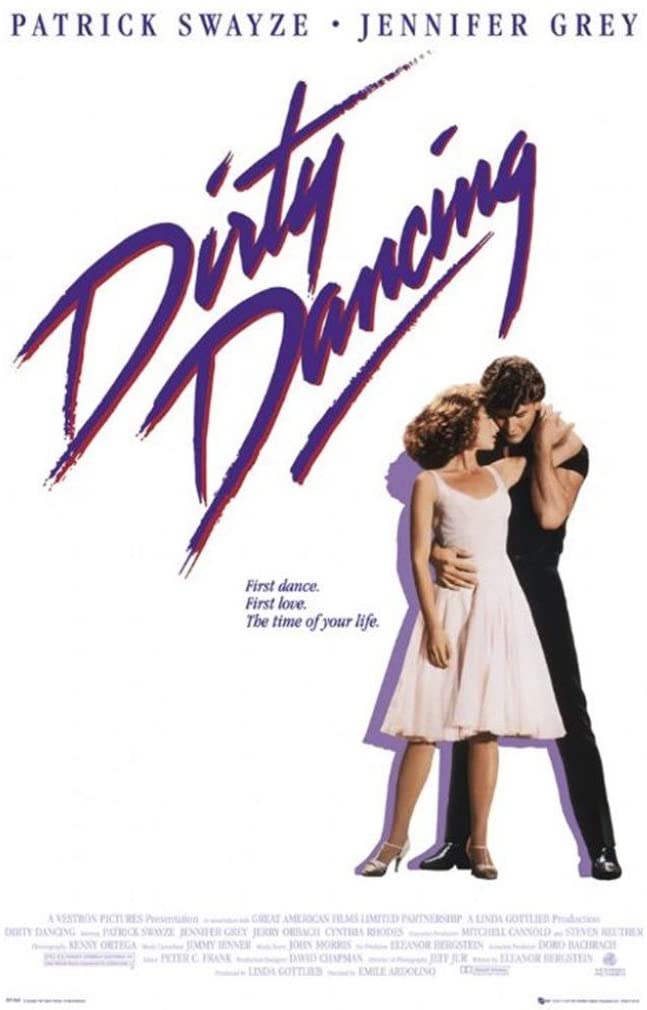

One of the beautiful things about motion pictures is that so often, You Just Never Know. The only studio (if that’s even the correct term) that would take “Dirty Dancing” was the venerable Vestron Pictures, which had previously only done VHS tapes. A few years later, Vestron was in bankruptcy, proving it’s better to be good than lucky.

Some megahits have surprised Hollywood veterans, but perhaps none with as much skepticism as “Dirty Dancing.” A producer supposedly recommended, “Burn the negative, and collect the insurance.” Roger Ebert gave the film 1 star and dubbed it “a tired and relentlessly predictable story of love between kids from different backgrounds”; 17 years later, he remained adamant that the plot was no more than “a clunker assembled from surplus parts at the Broken Plots Store.”

Fortunately, there’s this concept called The Customer’s Always Right.

“Dirty Dancing” proves why movie clichés exist — they work. Sure, it’s not the first time a girl fell for a guy from the wrong side of the tracks, nor is it the first time someone had the idea that American culture changed on Nov. 22, 1963, nor is it the debut of a rebellious teen. “Dirty Dancing” is not about formula. It’s a film of raw instinct and gut feelings, the way movies sometimes used to be made.

The genius in “Dirty Dancing” starts at the beginning. Yes, there is genius. This may be a fairly low-budget movie on first glance, but a longer look reveals how it’s put together by some supersmart people. “Be My Baby,” actually released in August 1963, the perfect song for this intro, plays over a black-and-white montage of people dancing. David Lynch would choose a similar type of scene (in color) for the beginning of his much more aspirational film, “Mulholland Dr.” There’s something happening here. Even people who may dislike the rest of the movie can watch this opening again and again, marveling at the connections humans share when dancing.

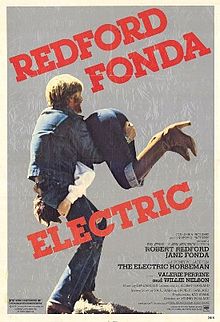

Patrick Swayze gets top billing in the credits. It’s too easy to attribute the movie’s appeal to him, though it’s true he couldn’t miss for about a decade. The thing is, the camera wants Baby even more. Sometimes, life imitates art. Swayze may have dismissed this project as just a job, much like Johnny Castle tries to dismiss Baby. But Jennifer Grey won’t let him off the hook. In scene after scene, she forces Johnny (and Swayze) to deal with her. Baby may be smart, but she is out of touch, she knows more about Southeast Asia than she does about blue-collar Americans. She just knows there is something about the way Johnny makes her feel, and he’s going to have to deal with it. Grey may even know too much for this character — she was 27 at the movie’s release. (Swayze was 35.) The end of the vacation neatly serves as the movie’s ending; it’s fair to speculate that Baby will ultimately be disappointed by Johnny, when it’s time for Mount Holyoke and the Peace Corps and there’s no more sneaking around. Fine. “Dirty Dancing,” like “The Bridges of Madison County” or “The Electric Horseman,” lives in the moment.

Thanks to some crutches of narration and characters greeting each other announcing details that they already know but the viewers don’t, we learn the Housemans’ summer vacation in the Catskills may be different this time. The resort operator, Max Kellerman, notes the family has come “after all of these years.” (Translation: By now, Baby has discovered boys and isn’t going to be satisfied with croquet.)

It’s pretty much the Week From Hell for Daddy (that’s what his daughters still call him). Jerry Orbach, far more famous as one of the cops in “Law & Order,” couldn’t solve the simplest of mysteries in “Dirty Dancing.” He may be a physician here, but he wouldn’t know what Baby was doing at night (or during the day) if Lieutenant Van Buren pointed it out to him. We just need him to shun Baby and condemn Johnny just when things are getting hot, to make them even hotter, to give Johnny the opportunity to utter the signature quote: “Nobody puts Baby in a corner.”

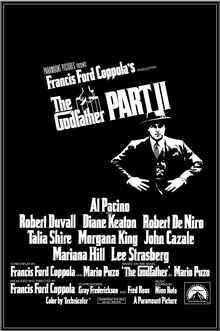

Abortion creates battle lines in public, but filmmakers seem not to fear polarizing audiences. “Dirty Dancing” might’ve been emboldend by “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” or even “The Godfather: Part II.” The former is more relevant here — if you’re doing a drama about a teen girl, abortion could be part of the conversation. Had there been higher expectations for “Dirty Dancing,” would the scene have made it? Plot-wise, it creates the opening that Baby needs to close in on Johnny. “Dirty Dancing” gives itself leeway by attaching this situation not to Baby or her sister but a peripheral character, exploited by the establishment, and allows Baby to opine on it. The movie attempts a statement about the availability of this procedure (while curiously appointing a negotiator and cheering section for this personal event).

The tunes are perfect. So much so that some may dub “Dirty Dancing” more a soundtrack than a movie. Song refrains tell us what’s happening or about to happen. The car rolls into the Kellerman lodge in the beautiful Catskills while viewers hear “Big Girls Don’t Cry,” a 1962 hit that beautifully lets Baby explain “That was the summer of 1963 ... before President Kennedy was shot.” At one point, Baby tries to give Penny a controversial $250 as viewers hear “Now your daddy don’t mind.” Even the kitsch is fantastic. Baby’s sister Lisa sings something to the effect of “You can wacka all ya wanna” in a Hawaiian skirt while a serious moment is taking place, and Lisa will finish the routine to the final steps. The Kellerman lodge even has its own farewell song, catchy enough that viewers quite possibly might want to see the entire preempted show during the credits.

Early on, Baby will sneak up to the lodge and observe the staff meeting as a faint preview of the show’s signature song, “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life,” anticipates the discovery she is about to make. “Time of My Life” was written by Franke Previte, John DeNicola and Donald Markowitz and is sung by Jennifer Warnes and Bill Medley. Warnes sang “Up Where We Belong” for “An Officer and a Gentleman.” Medley makes this 1987 composition feel authentically 1963. It won the Oscar for Best Original Song, the only nomination the film received, but a powerful one.

There might only be two sisters in the movie, but “Dirty Dancing” has plenty of cousins. The notion of opposites attract was tried earlier in another not-always-respected megahit, “The Way We Were.” Yes, Baby and Katie are different generations; Baby is aware of Ho Chi Minh, and Katie is preoccupied with Gen. Franco. But both movies thrive on a strong Jewish identity. That degree of authenticity overcomes the loose ends of the story.

“Dirty Dancing” and “The Way We Were” each hit paydirt in another way: the title. Without them, we might not be talking about these movies today. “Dirty Dancing” producer Linda Gottlieb knew it when she heard it: “That’s a million-dollar title! Now we’ll figure out the story.” Part of that story pushes the envelope. There are implications that the only dancing worth doing, even in a 1960s family resort, is the erotic kind, an entree or front for sex. The pros hired at the Kellerman lodge, we’re told early in the film, are “here to keep the, uh, guests happy,” an observation bolstered by later orders and offers. Don’t say you weren’t warned — there is “dirty” in the title.

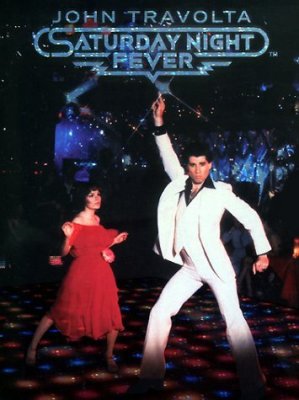

The “Dirty Dancing” rehearsals bear a lot of similarities to Tony and Stephanie in “Saturday Night Fever,” a raucous film in which the dancing is actually quite pure. The concluding performance at the “Dirty Dancing” talent show brings to mind the ending of “Grease.” Johnny’s loft will look a lot like the place where Swayze entertains Dr. Elizabeth Clay a couple years later in “Road House” (maybe even playing the same song?). Like “Breaking Away,” we see how the towners in “Dancing” can overcome the transitory elites.

“Saturday Night Fever” had other dynamics going on, but its practice sessions were not nearly as creative. “Dirty Dancing” takes Baby and Johnny out of the loft into a lake and onto a log, perhaps the film’s signature visual, occurring at the 42-minute mark. Then there are the lifts, and the jumps and simple bending, beautiful manifestations of the young and vibrant human body. “Dancing” also cleverly depicts the practicing with repetition. Some scenes, such as Baby giggling while Johnny strokes her chest, seem like the kind of outtakes shown during the credits, but somehow, in the middle of this film, they work.

Those giggles may not have been in the script. Swayze and Grey had previously worked/clashed together in “Red Dawn.” In his autobiography, Swayze complained that during the “Red Dawn” production, “She slipped into silly moods, forcing us to do scenes over and over again when she’d start laughing.” The reported tension between the two actors during “Dancing” somehow erupted in the best possible way: “They were human fireworks.”

Some episodes in “Dirty Dancing’ may prompt eye-rolling, but only one sequence risks derailing the movie. After all of their practices, Baby and Johnny will perform at the other resort as an elite pair. Baby is clearly awkward, but this crowd is too nice to boo. Should they? The filmmakers have set us up for great suspense — will Baby fail miserably and upend the whole plan to help Penny and land Johnny — only to give Baby a passing grade and some watered-down conclusion that, while her boldness is to be applauded, it’ll take years of this to share a stage with Johnny.

Overlooked in the dancing footage is the remarkable fashion show put on by Grey, no less effective than Julia Roberts in “Pretty Woman.” Baby stuns in jeans, skirts, tank tops, bodysuits, T-shirts, shorts, bras. Like Katie Morosky in “The Way We Were,” Baby has no grasp of her own beauty, a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. Grey does not appear topless (the movie is PG-13 after the filmmakers protested an initial R rating), but scenes in the lake are revealing.

One of the strangest movie characters of all time must be Robbie Gould, not the NFL kicker but the Yale-educated aspiring doctor who courts Lisa (who, by the way, does not resemble Baby in the slightest) whenever the plot requires. Robbie is determined to 1) say the stupidest possible things at the worst possible times and 2) get himself pummeled by every constituency at the resort, also whenever the plot requires. He’s the worst of the establishment. He attains privilege for his looks and pedigree so that he may exploit the underclass and brag about it, a character so deformed, he is comical. “Some people count. Some people don’t,” he shrugs.

Robbie is supposed to be a little too old for Baby, who is presented with an alternate suitor: Neil, the grandson and heir apparent of lodge owner Max Kellerman who is attending hotel school at Cornell and loves bossing the help around. “I’m known as The Catch of the County,” he boasts to Baby, and it’s not a referendum for Baby to decide; he already believes it. Before you condemn Neil, though, take a listen to him at the farewell show — the guy can sing.

The banter between the boys and girls tends to reveal another critical truth of “Dirty Dancing” — this movie is actually often funny. Narcissists supply a lot of the material. But there are subtleties too. While her sister practices in a Hawaiian skirt, Baby intently watches Johnny handling a serious situation and turns her head so fast, perfect timing, when Johnny glances in her direction, you almost have to howl.

Reactionaries are the underside of the appealing throwbacks of “Dirty Dancing.” There are lots of cars of the 1960s, there is ballroom dancing, and there is big band music. Despite opening declarations of croquet and volleyball, there doesn’t seem to be much to do at the Kellerman lodge, nor any other girls of the Housemans’ age present, but there are hints of the times when people played cards, charades and badminton to socialize and pass the time. Movies like “The Sweet Smell of Success” take us back to an appealing era when musicians wore suits and even the everyman believed in the value of formalities. But these pre-Boomers and their insular world lost the Generation Battle, as every generation eventually does, and gave way to change and diversity. Max Kellerman laments to his bandleader, “It feels like it’s all slipping away.” In “Saturday Night Fever” and “Dirty Dancing,” nearly all of the principal characters are white, except on the magic dance floor, where inclusion reigns, a world of its own. Baby is the only character in “Dirty Dancing” recognizing that change has come, time is passing the older generation by, that there’s going to be massive upheaval about the truths of this world, and you better be on the right side of history.

Buried deep in the ending credits of “Dirty Dancing” is the legalese, “Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual entities or events is purely coincidental.” That’s a chuckler, because “Dirty Dancing” is the brainchild of Eleanor Bergstein, who was born in 1938 and wrote the script based on her own life experiences spending summers with her doctor dad in the Catskills while dancing the Mambo whenever she could, winning contests. The real-life drama was not as feisty as the movie’s: “My parents were OK as long as I kept my grades up and was going on to college,” Bergstein says.

Gottlieb told a writer in 2012 that, in the 1980s, over lunch, Bergstein suggested doing a movie about two sisters who danced in the Catskills. “She said, ‘I grew up in Brooklyn, my father was a doctor, I was one of those kids who used to go across the tracks to go dirty dancing,’ ” Gottlieb recalled, and inspiration struck, only to be met by a brick wall — 43 times — in Hollywood. “What they all said was, ‘It’s small and it’s soft. These are all men ... They said ‘it’s a girls’ film, it’s a historical film and it’s about Jews.’ They weren’t wrong logically, but I always saw it as a very sexy movie.”

There are memories, and there are stories. Bergstein’s idea successfully differs from a host of movie projects that easily get offers but struggle with the notion of being “movies,” such as Cameron Crowe’s “Almost Famous,” which boasts far more critical and awards-show praise than “Dirty Dancing” — and about a third of the box office. (That’s 13 years later, not adjusted for inflation.)

The Catskills (the origin of the name is unclear) historically have been an arts haven and popular vacation destination for New Yorkers. The location’s most famous film is something Baby, in a few years, might well be interested in: “Woodstock.” Though set in the Catskills, “Dirty Dancing” wasn’t filmed there. Gottlieb indicated the decision was about cost. The movie’s Wikipedia page says the Catskills locations were shut down for the year. In any case, Gottlieb said Virginia and North Carolina were chosen as right-to-work states, helping to meet the small budget. Exceptional editing ties all the locations together.

What savvy director was chosen by Bergstein and Gottlieb to make this discount production work? Emile Ardolino, a New Yorker helming his first film after years of award-winning dance productions for PBS. The movie made Ardolino, in his early 40s at the time, one of the greatest of descriptions: “a force in Hollywood.” Just getting started, he would put together the hit “Sister Act” before his death in 1993 at age 50 from complications of AIDS.

Another sad footnote to “Dirty Dancing” is that Grey, by reported accounts, never got to enjoy the fruits of her massive success. A rising star in the 1980s with several major credits, she was a passenger in Matthew Broderick’s car when he struck another vehicle in Northern Ireland, killing a woman and her daughter just weeks before the 1987 release of “Dirty Dancing.” Grey was injured, and later suffered difficulties with medical procedures. Swayze’s career plateaued; this remarkably robust movie hero tragically died of pancreatic cancer at 57.

There is real life, and there is the Magic of Movies. That magic happens when talented people such as Bergstein and Gottlieb have the guts to try, and keep trying. This thing between Baby and Johnny is never going to work; that’s what many thought about the movie too. “Dirty Dancing” may be knocked for its clichés or its nostalgia or its politics. Try knocking it off the air. Bravo, Baby.

3.5 stars

(March 2021)

“Dirty Dancing” (1987)

Starring

Jennifer Grey

as Baby Houseman ♦

Patrick Swayze

as Johnny Castle ♦

Jerry Orbach

as Jake Houseman ♦

Cynthia Rhodes

as Penny Johnson ♦

Jack Weston

as Max Kellerman ♦

Jane Brucker

as Lisa Houseman ♦

Kelly Bishop

as Marjorie Houseman ♦

Lonny Price

as Neil Kellerman ♦

Max Cantor

as Robbie Gould ♦

Charles Honi Coles

as Tito Suarez ♦

Neal Jones

as Billy Kostecki ♦

‘Cousin Brucie’ Morrow

as Magician ♦

Wayne Knight

as Stan ♦

Paula Trueman

as Mrs. Schumacher ♦

Alvin Myerovich

as Mr. Schumacher ♦

Miranda Garrison

as Vivian Pressman ♦

Garry Goodrow

as Moe Pressman ♦

Antone Pagan

as Staff Kid ♦

Tom Cannold

as Bus Boy ♦

M.R. Fletcher

as Dirty Dancer ♦

Jesus Fuentes

as Dirty Dancer ♦

Heather Lea Gerdes

as Dirty Dancer ♦

Karen Getz

as Dirty Dancer ♦

Andrew Charles Koch

as Dirty Dancer ♦

D.A. Pauley

as Dirty Dancer ♦

Dorian Sanchez

as Dirty Dancer ♦

Jennifer Stahl

as Dirty Dancer ♦

Jonathan Barnes

as Tito’s Band ♦

Dwyght Bryan

as Tito’s Band ♦

Tom Drake

as Tito’s Band ♦

John Gotz

as Tito’s Band ♦

Dwayne Malphus

as Tito’s Band ♦

Dr. Clifford Watkins

as Tito’s Band

Directed by: Emile Ardolino

Written by: Eleanor Bergstein

Producer: Linda Gottlieb

Co-producer: Eleanor Bergstein

Associate producer: Doro Bachrach

Executive producer: Mitchell Cannold

Executive producer: Steven Reuther

Music: John Morris

Cinematography: Jeff Jur

Editing: Peter C. Frank

Casting: Bonnie Timmermann

Production design: David Chapman

Art direction: Mark Haack, Stephen Lineweaver

Set decoration: Clay Griffith

Costumes: Hilary Rosenfeld

Makeup and hair: Frida Aradottir, Marlies Vallant, David Forrest, Gilbert LaChapelle

Production manager: Jeffrey Hayes

Production supervisor: Eileen Eichenstein

Post-production supervisor: Tammy J. Green

Stunts: James Lovlett, Denise Amirante, Bill Anagnos, Norman Douglass

Special thanks: Michael Goldman

Special thanks: Jackie Horner

Special thanks: Jimmy Ienner