The ‘Rain Man’ steals hearts

while Tom Cruise steals show

Few observe that “Rain Man,” a staggering feel-good success of brotherhood, flirts with one of the riskiest Catch-22 sequences of movie history.

Disabilities are stressful. So are financial problems. To combine them in one film is an ambitious project. “Rain Man” remarkably gives cynics much to ponder. Before we get there, we have to give natural therapy its due.

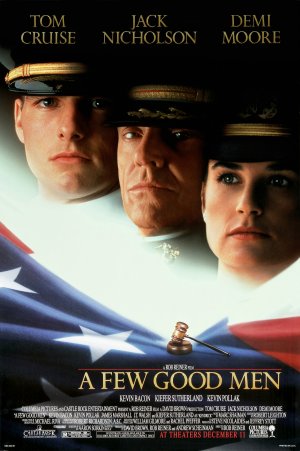

“Rain Man” belongs to that tree of films, including “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Good Will Hunting,” “Ordinary People” and “The Prince of Tides,” celebrating the triumph of nature over the institution. A character has maxed out on the amount of improvement he can get from conventional, uninspiring, by-the-book therapy, and it is now time to be exposed to more real-world, spontaneous environments where he can flourish.

If viewers gave these plots a serious reality check, they would likely be disappointed. Nurse Ratched’s patients would’ve raised costly hell on the boat and gotten the hospital sued, a weekend with Tom Wingo would sink Lowenstein’s career as a shrink, Will Hunting would’ve punched out Sean Maguire as soon as Maguire let go of Will’s throat, etc.

“Rain Man” is so compelling, it is perhaps the standard-bearer of Hollywood’s formidable anti-institution genre. Whether it’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Good Will Hunting,” “The Silence of the Lambs,” “The Shawshank Redemption,” “Terminator 2,” “Ordinary People,” it’s clear, being assigned society’s help is the wrong idea. People come out worse than they went in. The system isn’t there to improve, but to degrade and humiliate, run by incompetent or sadistic operators. Bruner is among the kinder, gentler, most responsible variety, but he’s insensitive enough to think it doesn’t matter if Raymond has a brother and that Raymond is permanently incapable of forming any kind of human relationship.

The story is so neatly designed, its implausibilities can be safely dismissed, primarily the issue of custody. We have a man unable to care for himself, who becomes demonstrably panicked in unfamiliar environments, who is taken from his home of 20-plus years as soon as he becomes a $3 million meal ticket, and not only is he mostly agreeable, police are never summoned.

If cops were called — and let’s be honest, they really should be — they would ruin a deeply moving road-trip experience that evokes memories of anyone’s most unforgettable family vacations.

“Rain Man” bears some startling parallels to a much different film released four years earlier: “Paris, Texas.” Both involve a barely communicative middle-age man taking a road trip west to his brother’s L.A. home. The brother’s plan for a simple flight goes awry when his sibling creates a scene at the airport. The exasperated brother has to find either exactly the right car or exactly the right food to keep the adventure going forward. The brother’s significant other, who helps to enlighten the discovery, is a woman who speaks with a foreign accent.

Each film presents at least one character who needs to realize a connection. To that end, we have road trips (in “Paris,” there are actually two) in which a relative who can’t really provide consent agrees to go along on a trip that would surely upend his life in far worse ways than are implied. That’s one nice thing about movies — they’re happy to dispose of those many hours driving through forgettable landscapes and any prospects of car trouble. These road trips are a crucial and very delicate balance. The character must go, or there’s no movie. But he can’t go eagerly, or there’s no drama.

Is “Rain Man” a true story? The answer is no. It is based on Kim Peek, a savant who curiously is not autistic. But dwelling on real-life and medical technicalities only overlooks a wonderful tale.

First we have the character, and no, this is not a film about an autistic person saying funny things (though the appeal of that is considerable and is all that some people get out of it). This is a film about Tom Cruise’s Charlie Babbitt, a hotshot with a fast lifestyle who is finally grounded by the things in life that really do matter.

He is running a small-time luxury car dealership during a time of great duress, and on top of that, his father has just passed away. This is an all-too-common occurrence for many people, a death at a very bad time, but this film throws a nice curve by offering an unexpected twist: Charlie might actually be glad to hear this news, because he has no love for his father but could certainly use whatever inheritance he might receive to solve his business woes.

So we get a double dose of unexpected theater, Charlie not at all troubled by the funeral, and then Charlie suddenly massively troubled by what he hears in the will.

Whether someone like Charlie, at his age (Cruise was 26 at the time of the December 1988 release), is truly capable of running a very-high-end luxury car business with apparently only one or two other employees is debatable. But Cruise pulls it off, because Charlie’s own personal motor operates at about 7,000 RPM, and he is impervious to stress.

It is that latter quality which enables the critical road trip to pass muster. Few, if any, people could stand a week on the road with someone like Raymond. But Charlie Babbitt most certainly can. He gets angry, he shouts, he argues, he gets frustrated at moments. But he never crosses the line of getting flustered or thrown off his game, a believable attribute of a high-risk businessman.

“You hear me!” Charlie exclaims. “I know you hear me. You don’t fool me.” But he does not stew or get depressed; he has made his point, and then he accommodates whatever Raymond needs to ease the jitters, and goes about his business. Most people who attempt what Charlie tries would give up after a few days (or less) and return Raymond. Cruise is convincing enough that we believe Charlie Babbitt is the one guy who wouldn’t.

Consider how well the writer has pieced together this intricate plot. Charlie is in desperate need of money — hardly the first film with this backstory, and admittedly the basics of his dealership operation are not well described and not a high point of the film — and suddenly has a chance to get some.

We are told Raymond is a “voluntary” patient (even though the same doctor later agrees Raymond can’t make decisions for himself), so that lets the film off the hook as far as police intervention. Then we are given two excellent reasons for why they must drive — Raymond refuses to board a plane, and it just so happens Charlie has inherited a car. Ray’s airport meltdown is an excellent scene in that it not only serves this purpose, but illustrates the risk Charlie is taking for both of them by removing Ray from his home.

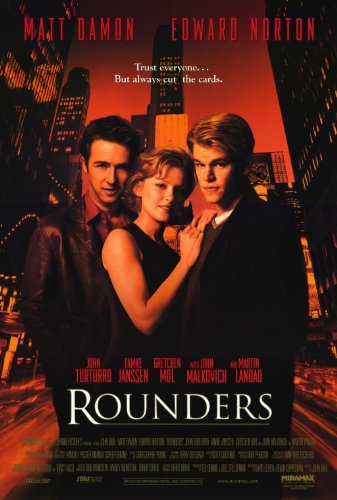

The road trip puts “Rain Man” in an eclectic mix of pictures including among many, “Easy Rider,” “Harry and Tonto,” “National Lampoon’s Vacation” and “Little Miss Sunshine.” The drive in the western half of the country, set against spectacular, evolving scenery, makes for such appealing cinema, one wonders why more films don’t try it (say, for example, the guys in “Rounders” building the bankroll on I-70 en route to the Strip).

The Babbitt car, a Buick Roadmaster, adds little more than panache, but of course every road-trip film must boast unique wheels; it would be boring to see them driving a Ford Taurus across Texas. As a component in Charlie’s life story, it is only fitting for him to drive it with Raymond.

Charlie’s decision to see a doctor in a small Texas town is a bit odd (wouldn’t he take him to a premier expert in Dallas?), but it is understandable that he is nearing maximum frustration, and this venture adds another unexpected twist when the doctor proves to be fairly impressive and is able to deliver what Dr. Bruner can’t — a layman’s explanation for how Raymond behaves. (Notice, though, that the doctor doesn’t ask how a brother such as Charlie would only now be questioning his brother’s behavior, or why a guy from Cincinnati and a guy from L.A. are seeking his consult in a small Texas town, two factors that would presumably make any physician wonder if the patient is actually in safe hands.)

Finally, the idea to play cards in Vegas, neatly built up over time with various examples of Raymond’s potential, and notice how they first pass through the city and move on before turning back. In the process, another gift of the unexpected, when lucky card-sharps actually don’t have the money taken away in some manner. All there is to quibble with is why a savvy, money-needy hustler like Charlie would exit the tables so soon when the grand winnings reach an all-too-convenient number of $86,000, just enough to pay off the car debts and get the watch back and maybe have a little left over.

Dustin Hoffman is miscategorized as “best actor,” but that is how these Oscar things work. His performance is sensational for its consistency. The lines are always delivered the same way, to the point of reaching national consciousness and lingering to this day. “I’m an excellent driver,” “Kmart, on 400 Oak Street,” “Yeah,” “40 minutes to Wapner,” “Who’s on first,” “Kmart sucks.” He also has a way of standing, in a new environment, hands against his chest, and fidgeting that keeps cemented the idea that this is still a person with disabilities.

One scene is questionable regarding Raymond’s behavior, and that is shortly after their journey begins when he grabs the steering wheel. Charlie scolds him mightily, but there is a fairly long-lasting grin on Hoffman’s face — suggesting that Raymond does indeed recognize the social value of pranking someone and is deliberately doing so, an understanding he is clearly not supposed to have. Presumably this scene exists to fuel Charlie’s suspicions that this is all a fake and to delay his acceptance of Raymond’s true nature, but the depiction of Raymond displaying satisfaction at annoying Charlie, rather than being scared about Charlie’s reaction or the lurch of the car, is a stretch.

The movie suggests Charlie’s form of therapy is more helpful than what Wallbrook provides. One way it does this is by showing Raymond as most comfortable when he is talking about things that are not part of his routine. In the beginning when he notices the car and sits in it with Susanna, he is happy to rattle off the details. Later he will freely sing “I Saw Her Standing There” to Charlie and explain why he was sent to Wallbrook.

There is a risk here by director Barry Levinson, and it does not necessarily pay off. Levinson has to make the Wallbrook staff competent, but unable to crack through some barrier that only a close relative like Charlie can breach. The Wallbrook people seem to prefer Raymond never budge an inch from his orderly world. Charlie’s experiences suggest that a therapist intent on improving Raymond’s ability to connect with the outside world should simply be jogging his memory with simple questions about family history. One wonders what exactly Dr. Bruner has been providing for Raymond all these years, other than a safe environment and a TV that always shows Wapner at the proper time. Is Bruner merely an enabler, and not a healer, of Raymond’s eccentric behavior? That argument has at least some substance, and calls into question the ending.

At the top of this review it was said that the lack of a police response to Raymond’s abduction is the most implausible element. There might be a better nominee — the idea that Charlie could grow up never knowing he had a brother who was institutionalized as a teenager. Neighbors talk. Somewhere along the line, a street-smart kid like Charlie would've heard whispers about Raymond, or noticed mail being sent to him.

Movie standards, however, are extraordinarily lenient for concealing family ties. Many famous characters don’t know who their fathers are, some aren’t even sure of their mothers, so the idea of a family in the 1960s merely avoiding acknowledgment of a child with disabilities is within the Hollywood-established boundaries.

Tom Cruise has never been much of an Oscar factor, unfortunately, and was left out again here. Hoffman’s dazzling work with a very limited character stole the public’s heart while Cruise was merely stealing the show. His Charlie Babbitt is relentlessly strong, and his gradual acceptance, admiration and love of Raymond is incredibly convincing. “Rain Man” was nominated for eight Oscars and won four, including Best Picture.

In two similar scenes does Cruise unleash his massive cinematic powers, courtesy of the cinematography of John Seale. One is at the casino bar, where Charlie watches a woman named Iris hit on Raymond. The other is in the L.A. meeting with Bruner and the independent doctor (played by Levinson). In both scenes, Raymond is in the front right of the screen, while Charlie watches, relaxed, from the left rear. From afar, not always in focus, Cruise is controlling the scene: He is protecting his brother from the potentially distressing conversations Raymond is having, but he has also reached a level of confidence in his brother that he will afford him the space to interact with others. He is sending the message that Raymond is an equal who just needs to be watched. His body language and expression deliver precisely what only legendary actors can do — show that he has made a kind of progress with Raymond that Bruner will never achieve.

The moviegoing public ignored the Catch-22 of “Rain Man.” Much of Charlie’s appreciation for Raymond stems from Raymond’s ability to win just enough — coincidentally just enough — money to rescue Charlie’s business and even get back his pawned watch. If they made no money in Vegas, and Charlie arrived in L.A. to a professional liquidation, bonding with Raymond would probably not seem so important, but in fact Bruner’s check just might. A cynic could say, with justification, that “Rain Man” incredibly depicts the worst of human values, that a fellow human being’s worth is essentially limited to whatever financial gains he/she can bring us.

That’s the half-empty assessment. The half-full view says that once Charlie began to accept Raymond, life started working for him again. Instead of his near-bankrupt existence, Charlie was actually going to make it as a human being, meaning whatever amount of money/support/luck he needs, he’s going to get, somehow. You take care of the people around you, they’ll take care of you.

And honestly, isn’t that the way it really works?

4 stars

(February 2009)

(Updated June 2020)

“Rain Man” (1988)

Starring Tom Cruise as Charlie Babbitt ♦ Dustin Hoffman as Raymond Babbitt ♦ Valeria Golino as Susanna ♦ Jerry Molen as Dr. Bruner ♦ Jack Murdock as John Mooney ♦ Michael D. Roberts as Vern ♦ Ralph Seymour as Lenny ♦ Lucinda Jenney as Iris ♦ Bonnie Hunt as Sally Dibbs ♦ Kim Robillard as Small Town Doctor ♦ Beth Grant as Mother at Farm House ♦ Dolan Dougherty as Farm House Kid ♦ Marshall Dougherty as Farm House Kid ♦ Patrick Dougherty as Farm House Kid ♦ John-Michael Dougherty as Farm House Kid ♦ Peter Dougherty as Farm House Kid ♦ Andrew Dougherty as Farm House Kid ♦ Loretta Wendt Jolivette as Dr. Bruner’s Secretary ♦ Donald E. Jones as Minister at Funeral ♦ Bryon P. Caunar as Man in Waiting Room ♦ Donna J. Dickson as Nurse ♦ Earl Roat as Man on Wallbrook Road ♦ William Montgomery Jr. as Wallbrook Patient Entering TV Room ♦ Elizabeth Lower as Bank Officer ♦ Michael C. Hall as Police Officer at Accident ♦ Robert W. Heckel as Police Officer at Accident ♦ W. Todd Kenner as Police Officer at Accident ♦ Kneeles Reeves as Amarillo Hotel Owner ♦ Jack W. Cope as Irate Driver ♦ Nick Mazzola as Blackjack Dealer ♦ Ralph Tabakin as Shift Boss ♦ Ray Baker as Mr. Kelso ♦ Isadore Figler as Pit Boss ♦ Ralph M. Cardinale as Pit Boss ♦ Sam Roth as Floorman ♦ Nanci M. Harvey as Lady at Blackjack Table ♦ Kenneth E. Lowden as Guard in Video Room ♦ Jocko Marcellino as Las Vegas Crooner ♦ John Thorstensen as Train Conductor ♦ Blanche Salter as Woman at Pancake Counter ♦ Jake Hoffman as Boy at Pancake Counter ♦ Royce D. Applegate as Voice-over Actor ♦ June Christopher as Voice-over Actor ♦ Anna Mathias as Voice-over Actor ♦ Archie Hahn as Voice-over Actor ♦ Luisa Leschin as Voice-over Actor ♦ Ira Miller as Voice-over Actor ♦ Chris Mulkey as Voice-over Actor ♦ Tracy Newman as Voice-over Actor ♦ Julie Payne as Voice-over Actor ♦ Reni Santoni as Voice-over Actor ♦ Bridget Sienna as Voice-over Actor ♦ Ruth Silveira as Voice-over Actor ♦ Jonathan Stark as Voice-over Actor ♦ Lynne Marie Stewart as Voice-over Actor ♦ Arnold F. Turner as Voice-over Actor ♦ Gigi Vorgan as Voice-over Actor ♦ Richard A. Buswell as Car Driver ♦ Barry Levinson as Doctor ♦ Matthew Mattingly as Autistic Pianist ♦ Aaron Weiler as Airport Security Guard ♦ Mark Winn as Restaurant Patron

Directed by: Barry Levinson

Written by: Barry Morrow

Written by: Ronald Bass

Producer: Mark Johnson

Associate producer: David McGiffert

Associate producer: Gail Mutrux

Co-producer: Gerald R. Molen

Executive producer: Peter Guber

Executive producer: Jon Peters

Original music: Hans Zimmer

Cinematography: John Seale

Film editing: Stu Linder

Casting: Louis DiGiaimo

Production design: Ida Random

Art direction: William A. Elliott

Set decoration: Linda DeScenna

Costume design: Bernie Pollack

Unit production manager: Gerald R. Molen

Makeup and hair: Rick Sharp ♦ Joy Zapata ♦ Ed Butterworth

Consultant — autistic behavior: Bernard Rimland Ph.D.

Consultant — autistic behavior: Arnold M. Rosen M.D.

Consultant — autistic behavior: Bodil Sivertsen Ph.D.

Consultant — autistic behavior: Ruth C. Sullivan Ph.D.

Consultant — autistic behavior: Peter E. Tanguay M.D.

Consultant — autistic behavior: Darold A. Treffert M.D.

Special thanks: Ted Bafaloukos ♦ Roger Birnbaum ♦ Ken Friedman ♦ Kim Peek ♦ Peggy Siegal