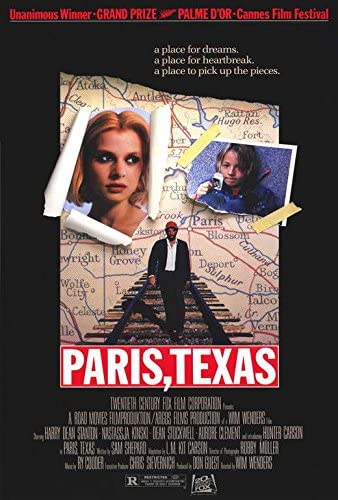

In ‘Paris, Texas,’ a man begins to repair his family by tearing another apart

What happened between Travis and Jane? Sometimes, filmmakers tell us the most when they tell us so little.

If the story of Travis and Jane were sliced into fourths, “Paris, Texas” would account for about Parts 2-3. We don’t know how this will end, and we certainly don’t know how it started. Hitchcock liked to say that a bomb going off was not suspense, but the audience knowing there was a bomb ticking under a table was suspense. “Paris, Texas” is a rare film in which the characters, all of them, know far more than their audience and are not about to give anything up.

Its director, Wim Wenders, “is attracted to the road movie,” according to Roger Ebert in his 2002 “Great Movie” review. In the early 1980s, Wenders sought out the acclaimed playwright and actor Sam Shepard, notable for the spare and poetic, to “tell a story about America,” one that became very much a work in progress. “Sam will write it as we go along,” Wenders wrote, in an apparent message to the film’s financiers, according to someone who wrote in 2018 of reviewing Shepard’s notebooks. To further enhance the script’s Lone Star sensitivities, Wenders sought “some rewriting” from independent film figure L.M. Kit Carson, who “embodied Texas individualism.” Carson was married for a time to Karen Black. His greatest contribution to the film might be the presence of their son, Hunter, in a demanding supporting role.

Ebert wrote that “Paris, Texas” is “always compared” to “The Searchers.” But more astonishing parallels can be drawn to “Rain Main,” released four years after “Paris, Texas.” A barely communicating man is driven across the Southwest by his brother, to the brother’s home in Los Angeles, after an embarrassing airport incident in which the man refuses to fly on a plane. The brother’s significant other speaks with a foreign accent. In each film, a relative is essentially kidnapped for a car trip, apparently willing to go but unable to provide legal consent, yet his guardians choose not to summon authorities. Oh, and there’s a classic old car, too, although in “Paris, Texas,” the likable automobile only emerges for the ride back.

The victory, or call it necessity, of “Paris, Texas” is for Travis to deliver his son to the boy’s mother. With it will come heart-breaking, unexplored tragedy, but there is a quiet understanding among all the players that this is an acceptable plan. Or at least that it is justifiable, an acknowledgment of self-determination, that what Travis is doing is not reliable, but he has the right to attempt to improve his family.

The opening credits appear in blood-red capital letters, implying “Paris, Texas” might be horror material. Travis’ appearance, expression and silence perhaps could be explained by a “Sling Blade” moment. Those edges soften by the time he meets his son, but their awkwardness together suggests further potential for danger. Travis tries to walk Hunter home from school. Travis will put Hunter in the back bed of his car, no seat belt, on the highway. Travis will leave Hunter on a street in Houston; he’ll leave Hunter in an empty hotel room. The boy comes through without a scratch. Throughout, there are hints of child endangerment, none more so than the ending, leaving the boy to be raised by a defeated woman who works in a peep show.

Harry Dean Stanton, one of the most beloved and prolific character actors, is handed here, like Art Carney in another road-trip film, “Harry and Tonto,” the role of a lifetime. While Carney walked away with the Best Actor Oscar in what might have been the greatest year of film, Stanton couldn’t even elicit a nomination. In fact, Stanton, Ry Cooder and “Paris, Texas” in its entirety were completely shut out by the Academy Awards, which do, at least occasionally, acknowledge the greatest films, including sometimes those that don’t fit neatly into categories. This massive oversight, in this case, should be worn as a badge of honor.

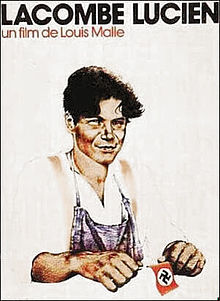

Dean Stockwell, a Hollywood legend who never gets enough credit, is limited in what he must do as Travis’ brother Walt. Wenders is hardly the only auteur to notice Stockwell, whose prodigious list of credits, dating back to World War II, includes films by Robert Altman, David Lynch, Elia Kazan, Dennis Hopper and Francis Coppola. As a blue-collar elite, he is spot-on, a reliable businessman, successful enough to employ a housekeeper, not necessarily a deep thinker. His observations indicate he knows much of this backstory, even if the latest chapter is perplexing. His wife, Anne, is curiously played by the French actress Aurore Clément, whose debut was in the magnificent “Lacombe, Lucien.” Many movie couples are a mismatch. This is clearly one of them. Wenders might be borrowing from Rainer Werner Fassbinder, a fellow German New Wave maestro who specialized in pairing up people whom no one would believe are actually together. Maybe Wenders is showing us that Walt lives the dream that Travis can’t, that Walt has connected with the real Paris and refused to be tied down to a small town. Stockwell and Clément never really click together, but each delivers in their moments with Travis. (Clément appeared in the chopped plantation scenes of “Apocalypse Now” and is married to “The Godfather” production designer Dean Tavoularis.)

One of the setbacks to the script is that dialogue, no matter how rich, is not visual, and reliance on it in a film is a crutch. Wenders counts on the majestic desert photography of Robby Müller to make a point about the bleak life Travis has been living, but the Mojave can’t supply the name of a Houston bank. Several important revelations are delivered via phones. Walt learns in a call at work that his brother is in a Texas hospital, and he approaches Anne, also at the business, and tells her in this critical exchange: “I just got the strangest phone call ... They say they found Travis.”

He tells her he will go get Travis, and her reaction inadequately betrays what this means for their family. “What about Hunter? What am I supposed to tell him?”

“I guess you better tell him the truth,” Walt suggests, a comment that cements that the couple will not attempt to block Travis from the natural outcome of his family relationships.

Walt’s initial attempt to find Travis ends in frustration at the remote border hospital. Why did Travis not wait for him, and where is Travis going? Of course Travis can’t walk across the Southwest in shredded shoes, suit and tie, and he doesn’t attempt hitchhiking. Travis is a long way even from Paris, Texas. When Walt first spots him walking on train tracks, like Charlie Babbitt in “Rain Man,” Walt demands to know what Travis is thinking and why he could be resisting Walt’s plan. “What’s out there?” Walt asks, pointing to the western sunset. “There’s nothing out there.”

Their first scenes together are some of Wenders’ most powerful filmmaking. Which brother is controlling the situation? Walt has the car and more importantly, though we have yet to learn of Travis’ intentions, the boy. Travis has the vulnerability. Given his actions, if he’s left alone, he might die. Walt’s interest in bringing Travis to Los Angeles is twofold. Walt doesn’t want a guilt trip, and he thinks he might want to know the story of the last four years, although Walt asks about it as if he’s talking about last weekend, in a way that suggests he has heard bad stories from Travis previously and might not want to know much about this one. Travis is not associated with drug use or heavy drinking; if he were, his runaway decision would not be acceptable. But he comes across as someone whom trouble might like to find. Walt explains he’s not being a surrogate dad: “I’m just trying to help you Trav, that’s all,” but Travis, like many famous movie characters, makes clear he has little interest in being helped.

“Are you gonna leave me?” Travis wonders, after he forces the two of them off a plane, perhaps the film’s funniest given the plane’s location. “No, I’m not gonna leave you,” Walt assures, to which Travis responds, “It’s all right if you leave me.”

Travis’ behavior leading up to the plane incident is an indication he might be on the autism spectrum, but his symptoms appear more likely of someone experiencing shock or PTSD. He might be refusing to fly because he has no control of the situation, or because he is determined to see the country from the ground level, or perhaps he is anxious about confinement. With mutes, there is always drama about when they might speak. The first word Travis says is “Paris.” He says it three times. “Did you ever go to Paris?” he asks Walt. He wants to go there now, not explaining he means Paris, Texas.

There is endless irony in the title. “Paris” and “Texas” are formidable terms, one signifying the world’s culture capital; the other a statement on independence, vigor, resilience, land, opportunity. Together, they are oil and wine — worlds apart, much like Travis’ aspirations and reality.

Children can think in the now, unburdened by baggage. The initial response of little Hunter to the arrival of his father is not positive. He wants to believe that the “dad” that he trusts is his real dad. He sees in Travis not so much a threat as someone who could embarrass him. Hunter’s acceptance is a must for the drama, and Wenders stakes it out beautifully. Travis will try unsuccessfully to walk Hunter home from school. As Travis’ intentions are gradually revealed to be pure, the boy relents, and when Travis crosses the street, it is a victory for any father who ever tried to do the right thing.

The Super 8 home movies in “Paris, Texas” undoubtedly remind many viewers past the age of 50 of family gatherings. Cooder’s music here changes tone, a beautiful accompaniment to the living-room theater. (A similar, quieter tone will surface during a closing conversation.) This is our first look at the mysterious Jane, an important and debatable decision by Wenders. Watching the film, the group smiles at some of the images but appears near tears at shots of Jane, as if she were dead. Hunter concludes, “That’s only her in a movie. A long time ago. In a galaxy far, far away.”

Well aware of the threat to their parenthood, Walt and Anne have likely prepared long before this day for Travis’ reemergence and accept it without alarm. Their comments indicate they have told Hunter the truth but not too much of it, out of protection for Hunter, not themselves. They do not have their own children (unclear why). They believe they are the luckiest parents in the world to have ended up with Hunter. It came about because of others’ misfortune. So there is guilt linked to that happiness — so much so that they will open the door to undoing it.

Walt assures, “We’re not gonna lose Hunter,” though his inaction suggests otherwise. Anne admits to Walt she is afraid “of what will happen to us if we lose Hunter.” She faults Walt for “pushing them together; it’s almost as if you wanted him to leave.” Yet it is Anne who willingly reveals the missing ingredient of Travis’ journey. She informs Travis of three critical things, 1) Jane’s whereabouts and 2) Jane’s lingering interest in Travis and 3) Jane’s interest in supporting her son. Did Anne make a mistake in providing this information to Travis? No. She has been desperate for completeness for several years, and her disclosure brings it much closer.

“Travis, I don’t want to feel I’m hiding something,” Anne explains.

She also reveals that the decision to have Hunter raised by Walt and Anne was made by Jane, not the courts. It is not unusual for an uncle or aunt to raise a child; this spartan tale declines to reveal whether grandparents or relatives of Jane might have expressed interest. Jane may have sensed Anne and Walt longing for a child.

Travis at this point may be lacking in memory, but not defiance. Referring to their split, he insists to Anne, “She stopped being a mother to him a long time before that.”

The reverse road trip of “Paris, Texas” risks belaboring the film. Diners appear in many films for the comfort they bring. Pancakes, coffee, any kind of breakfast food, costing only a few dollars, almost any time of day. Wenders is fascinated by American mobility, the highways and airplanes. It’s fair criticism that he makes the eastbound trip a little too easy. That the boy would not be missing his friends or Walt and Anne, or his clothes, and would behave so enthusiastically, stretches belief. (Hunter does wear a NASA jacket — guess where Mission Control is.) A man and a child staking out a bank drive-thru would probably at some point draw police attention. Of course, despite falling asleep, they must identify Jane that day, because missing her would involve another month in Houston of doing nothing. Wenders saves this predictability with one of the most clever car-chase scenes. If you say you did not actually believe that they might have followed the wrong vehicle and never have reached Jane, you are not telling the truth.

Hardly a Texas native, Nastassja Kinski, of Germany, is cast as Jane. Directors tend to keep coming back to familiar actors. Kinski’s debut was in Wenders’ 1975 “The Wrong Move,” the second installment of the director’s “road movie trilogy.” At times during Jane’s remarks, Kinski’s European accent is detectable. Is this an irrelevant side effect, or a subtle suggestion that Travis found an immigrant for his European ideal? In one of the more memorable movie tics, Kinski runs her hands through her hair, constantly, revealing a discomfort with what Jane is doing.

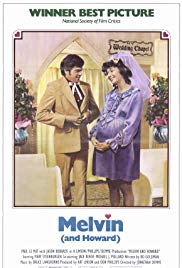

Having found Jane’s workplace, Travis could surely confront her at home. But her low-budget apartment wouldn’t include such features as two-way glass, and Wenders needs an emotional discovery here, such as when Paul Le Mat sees Mary Steenburgen parading through a strip bar in “Melvin and Howard.”

When Travis enters Jane’s place of work, an adult club of some kind of kinkiness, he immediately hears a woman explaining the environment that these women find themselves in. None of them, at this moment, appear sexy. The woman is saying, apparently to no one in particular, that because the female workers spend so much time on the job with men, most of them live alone. But, she is heard to say, “It’s tough living alone in a city like this. A lot of violent things happen here. Stuff like, like rape, and murder.” She says it’s a “tough decision” whether to live with a man or a dog.

“A lot of sick people out there,” another woman agrees.

So it is implied that women who work in this place come from abusive environments. That’s what they know. It’s entirely possible that, after finding Jane’s place of work, Travis might bump into her upon opening the door, but Wenders needs to build the drama, and so Travis will first make eye contact with a woman who resembles Jane before confirming, when she is provided to him, that she’s not Jane.

Once he is presented with Jane, we see the first evidence of indecision on the part of Travis. Growing frustrated, Jane will ask, “Is there something you wanna tell me.” He appears torn at witnessing the life she is leading before old reflexes return; he tells her she can go home with her customers and demands to know “how much money do you make on the side.”

Upon realizing he has hurt her again, he implores her not to leave. “Please. Please don’t go, I’m sorry.” Is that what Travis wishes he said four years ago? Yet he finds himself unable to continue, perhaps because he is not as ready for this conversation as he thought, or perhaps because Wenders still needs him to deliver an eloquent, taped farewell to Hunter in a hotel room.

“The biggest thing I hoped for can’t come true,” Travis tells Hunter on that tape. “I know that now. You belong together with your mother. It was me that tore you apart. ... I can never heal up what happened. That’s just the way it is. I can’t even hardly remember what happened. It’s like a gap.” He will save most of the confessional for Jane. Wenders brings life to this signature dialogue by having Travis turn around his chair, seeking even terms in which neither he nor Jane is allowed a look at the other. Finally, there is a coming together. One of the film’s supreme shots is Travis’ head superimposed on Jane through the glass.

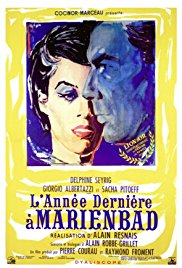

The sense of amnesia brings to mind a faint parallel to “Last Year at Marienbad,” in which a man tries diligently to inform or remind a woman of a significant previous event. Both films deem what happened in the past a macguffin and assert that what matters now is a decision by the woman. X needs A to leave with him; Travis needs Jane to go to a hotel.

How eager is Jane to see Hunter? It must not have occurred to Travis that Jane has known of Hunter’s whereabouts for the last four years and presumably could’ve come to retrieve him at any time. She might’ve been afraid the boy would reject her, or she might’ve believed herself to be an unfit parent. Travis’ visit and testament is the validation she needs but did not expect.

One of the most easily cured movie afflictions is anger. A lot of drunken characters never sober up, and a lot of womanizers just can’t help themselves. But give a movie character a horrifically bad temper, and he can straighten himself out with a little coaching or a little perspective. Will Hunting needed the former; Travis Henderson, like Tony Lip, is old enough to benefit from the latter. “I just didn’t realize how much rage I had,” he will tell Anne, a rage that, for the duration of this film at least, has been squelched, maybe forever, maybe not.

The movie ends, but the hard work is still to come. Jane will call Walt and Anne, probably shortly after meeting Hunter. She’ll tell them she’s so sorry that Hunter was taken from them and will make arrangements to “work things out,” but she’ll need a few days to get this settled. Walt and Anne will undergo counseling. Hunter will, presumably in short order, wonder about no longer having his friends and school and his own room and a housekeeper.

Travis, who probably coincidentally shares the same first name as the protagonist of “Taxi Driver,” is not an antihero. He is attempting the right thing at a horrible cost. Walt and Anne are the heroes, giving their hearts to a child who is not their own knowing he could always be taken away.

Some of the descriptions of “Paris, Texas” bear startling similarities to a famous court battle that took place in Illinois a decade later called the “Baby Richard case.” That boy’s mother had placed him with an adoptive family while apparently telling the father that the baby had died, only to have the father learn the truth and gain custody when the boy was 4. There was media outrage. Hunter’s detachment is much softer. That’s a must, or we’d never forgive Travis.

Travis drives off from Houston, and where is he going? He has told Walt and Anne that he will reimburse them for expenses such as the car, but that doesn’t mean he must return to L.A. He has no money, no possessions, no anchor. He will probably call Walt and Anne from a pay phone outside a diner and inform them that Hunter is with Jane. In “Kramer vs. Kramer,” there would be reliance on the system, probably including court arguments and social workers. Not in Texas, where Walt and Anne choose to let nature run its course.

4 stars

(May 2020)

“Paris, Texas” (1984)

Starring

Harry Dean Stanton

as Travis Henderson ♦

Nastassja Kinski

as Jane Henderson ♦

Dean Stockwell

as Walt Henderson ♦

Aurore Clement

as Anne Henderson ♦

Hunter Carson

as Hunter Henderson ♦

Bernhard Wicki

as Doctor Ulmer ♦

Sam Berry

as Gas Station Attendant ♦

Claresie Mobley

as Car Rental Clerk ♦

Viva Auder

as Woman on TV ♦

Edward Fayton

as Hunter’s Friend ♦

Socorro Valdez

as Carmelita ♦

Justin Hogg

as Hunter - Age 3 ♦

Tom Farrell

as Screaming Man ♦

John Lurie

as ‘Slater’ ♦

Jeni Vici

as ‘Stretch’ ♦

Sally Norvell

as ‘Nurse Bibs’ ♦

Sharon Menzel

as Comedienne ♦

The Mydolls

as Rehearsing Band ♦

Brandy Tipton

as Hunter’s Girlfriend (scenes deleted)

Directed by: Wim Wenders

Written by: Sam Shepard

Written by: L.M. Kit Carson (adaptation)

Written by: Walter Donohue (story editor: Channel 4)

Producer: Anatole Dauman

Producer: Don Guest

Associate producer: Pascale Dauman

Executive producer: Chris Sievernich

Music: Ry Cooder

Cinematography: Robby Müller

Editing: Peter Przygodda

Casting: Gary Chason

Art direction: Kate Altman

Costume designs: Birgitta Bjerke

Makeup and hair: Charles Balazs

Production manager: Karen Koch

Post-production manager: Udo Heiland

Assistant director: Claire Denis

Dedicated to: Lotte H. Eisner

Thanks: Barbara von Weitershausen