Kilmer can’t get much higher

in a biopic that lit few fires

Astoundingly, Val Kilmer never received an Oscar nomination for “The Doors.”

Rarely does a celebrity film character match the stature of the real thing. Kilmer’s surpasses it. Many annoyed critics never realized, this movie gave them a better Morrison than the one they actually remember.

“The Doors” is a tragedy that no one wants to believe is a tragedy. Thus director Oliver Stone has serious problems with expectation. Many regard The Doors as an elite band with an over-the-top frontman, known as much for barechested photos, defying Ed Sullivan, bad poetry and an ugly Miami court conviction as for the music, a blend of rock/pop/psychedelia/poetry that remains a staple of classic rock stations, perhaps not appreciated quite as reverentially as material from Led Zeppelin, Hendrix, the Stones, Pink Floyd. The Morrison Doors managed six albums, several tours, serious fame and about all the perks that go with it. The fact that one of ’em drank himself to death? This isn’t exactly “Brian’s Song.”

Stone avoids a head-on confrontation with a powerful theme — the horror that alcohol can bring to our lives. He sees it as a factor in Morrison’s downfall but also as the effect of a creative genius. He freely admits his biases. “I first heard The Doors in Vietnam,” Stone says. It was early 1968; “that first album was a blow-away album.”

Appreciating this film requires a much more serious view of The Doors than many believe worth giving. The band was more talented than you probably think, especially Morrison ... who might’ve been an indulgent, spoiled rock star, but was also one of countless human beings who hurt people close to him and then paid the ultimate price, because he couldn’t be helped.

“The Doors” is a sum-of-the-parts endeavor, struggling to fight off the cliches of a rock biopic and tell a story by descending into the tortured genius of a protagonist. Too often we see a character whose artistry and indulgences have gone unchecked, completely lacking the healthy competition that galvanized the Beatles and drove them to immortality. There will not be a neat ending here, but there are successes, in ways Morrison never would’ve realized.

The story of “The Doors” is well known, and Stone does not try to change it. Nor does he even take significant artistic license with the band. Despite the inevitable carping about certain inaccuracies, the film is notable for how much it adheres to history. Stone often uses text descriptions, with year, to introduce a landmark concert or scene. This is perhaps not so difficult because the Morrison Doors were a very short-lived phenomenon, about four or five years of megafame, then it was over.

By the time this film came together (it was released in March 1991), Stone was white-hot, dominating the moviegoing consciousness in the late 1980s and early ’90s with films such as “Platoon,” “Wall Street” and “Born on the Fourth of July” (“JFK” would be released later in 1991). “The Doors” produced the predictable stream of criticism Stone has received for other films on famous figures, such as Nixon, George W. Bush and the Kennedy assassination, which is that Stone is dabbling in rewriting history in part with fictitious scenes. Those are adequate criticisms for VH-1 or PBS documentaries. One thread runs through these Stone films, that it’s not so much about what the person precisely did, but how we feel about what they might as well have done.

“This was not meant to be a biography,” said Kathleen Quinlan, who portrays Patricia Kennealy in a composite-type character. “This is Oliver’s vision.”

Perhaps most vocal was Doors co-founder Ray Manzarek, who is wonderfully candid and down-to-earth in discussing the band and unfortunately did not like the film. (In fact, he planned to do his own version.) Manzarek has been quoted as saying Stone’s portrait of Morrison is wrong, exaggerates Morrison’s drinking and fails to show his sense of humor and friendship, and is something of an insult. Bandmate Robby Krieger is less critical, saying much was left out of the film, but “I thought that it turned out pretty good.”

Stone, in interviews and in his director’s commentary, mentions that Manzarek was “very destructive to me” and possessed an “unnatural” dislike of him. Stone points to one scene he says enraged Manzarek, where the other band members have agreed to license “Light My Fire” for a Ford commercial only to be upbraided by a drunken Morrison. But another scene, at the Ed Sullivan studios, also suggests that Manzarek was OK with shunning artistic purity, rationalizing the show’s request to remove “higher” from “Light My Fire” by noting, “The Stones changed when they played here.” Stone, who cites many pages of Morrison interview transcripts he has read, says the Ford commercial did not come to fruition, only because Morrison’s criticism blocked it. He points to this as a valid use of artistic license.

A related use of artistic license is also very compelling. It is Stone’s depiction of the band at the Ed Sullivan show, getting their make-up and instructions for their seminal moment of breaking on through into mainstream pop culture. Eventually they are asked/told not to say “higher” in “Light My Fire.” This is the equivalent of teeing up a golf ball for Tiger Woods. Stone uses clever little dialogue to show how the band, in September 1967, is setting the global curve for hipness. The Sullivan aide refers to them gingerly as “boys,” cautiously using cemented-in-’60s terms “dig” and “groovy.” The performance didn’t happen as Stone depicts — Morrison didn’t sneer the word into the camera — but Stone’s version is more satisfying and what we feel like Morrison would do. (One wonders if reverse psychology might’ve worked here, for example, if the same producer had simply asked Morrison to say “higher” as loud as possible because the show wanted to generate controversy. Nevertheless, a decent message is delivered that is often ignored to this day, if you’re not fully comfortable with an artist’s material, don’t ask them to appear on your show.)

Stone relies on recurring scenes and imagery to get inside Morrison’s head. Most prominent is a childhood vision of a family of American Indians along the side of a highway, injured in a car accident. As inspiration to a rock star, this feels a reach. Morrison is said to have spoken often of this tragedy, although according to various accounts his family is uncertain as to what they actually saw.

The image of an old American Indian shaman appears during critical moments of Morrison’s life as haunting the singer but fails to connect the childhood trauma to Morrison’s adult excesses. Even far less convincing is Stone’s decision to portray Death as a bald character in various costumes — played by Stone associate Richard Rutowski — shadowing Morrison as some kind of timeless stalker whose true nature probably isn’t apparent to most viewers. Stone said the Death character was not planned, but a gut decision. “Let’s just go for it,” he decided at one point.

Morrison is also shown often at night in dimly lit lofts or bedrooms with one of his two prominent companions, Pamela Courson and Patricia Kennealy, almost always in some form of disconnect or debate. Stone freely admits that his depiction of the female characters is his biggest regret. Meg Ryan, as Patricia Courson, never clicked. “She was shocked by the ’60s, and she was, like, doing it as research,” Stone said.

The problem with Quinlan was not suitability (her performance is stellar, and her body is one of the best you’ll ever see nude from a leading actress), but characterization. Stone regrets that he gave her the name Patricia Kennealy because he says the character was drawn from several women close to Morrison, not just Kennealy, who appears in the movie and offered advice during filming but was offended by the resulting depiction, notably a scene involving an abortion discussion that Kennealy says prompted laughter in the theater she was in.

Kennealy humorously notes that her witch-officiated wedding in the film is accurate only because she was in the scene and told Stone how to do it, but that Stone nevertheless succumbed to “cheap farce” and “Greek tragedy.” Stone says “Kathleen was a real trooper.”

The scenes with the women feel limitless, and not necessarily in a good way. One of Stone’s themes is that Morrison might’ve been a megastar but was no act. Stone arranged for permission from Courson’s parents to cite Morrison’s unpublished poetry and much of it is delivered here, of debatable quality, under various influences, suggesting crazier things were going on in Morrison’s head than on stage. The movie drags during the acid trips and suicide threats. If only we could get through to this person, figure out why he’s so obsessed with death and drugs and why he won’t just come down to the studio and jam with us ...

A couple of early scenes are perhaps unnecessary but help advance the character. Directors must deal with the introduction of a couple as they do violence; it occurs in every film and so there has to be something unique about it. Morrison meets Courson by stalking her home and climbing a tree up to her window, a predictable suggestion this is someone who doesn’t always play by society’s rules. We see Morrison abandoning UCLA film class after discussion of his film, a sign this is a person with limited patience for those who don’t appreciate his nuances.

The conventional scenes, and there are not many, are well-inserted at appropriate times, simple reminders of the band’s extraordinary appeal. A lesser film along the lines of a rock doc would dwell on various record-breaking concerts, glorious moments performing “Roadhouse Blues” and contract rewards and disputes. Stone only briefly teases with songwriting, showing the introduction of “Light My Fire” in a rich, moving scene of frustrated young artists quickly realizing they’ve got it. A couple other recording sessions quickly become unhinged. Stone is not interested in where the albums ranked on the Billboard charts or who wrote the songs or how much money they made.

It is noteworthy that Stone mentions early in his director’s commentary, as Morrison and Manzarek are on the beach, that the hair is wigs. In some of Kilmer’s early scenes, the hair looks ridiculously fake. For Frank Whaley’s Robby Krieger, this problem persists through the film, drawing poor comparisons to the comical Lance character of “Pulp Fiction,” which was released a few years later.

“The Doors” is partly about how a group of people of similar ability deal with one member with a freakish talent. They can orbit his universe but never really penetrate it. The success comes in recognizing that. The band is neatly depicted, characters matching the real artists in several ways. You have the two musicians, Densmore and Krieger, who just want to play, effective, but not megastars. In a fairly recent PBS documentary, Densmore remarks that as a professional, there were times he’d just wish Morrison would show up and practice on schedule. Indeed, his character complains of Morrison early in the film, “The guy never does what’s rehearsed.” But he explains in the documentaries, upon meeting Morrison for the first time at a band gathering, he decided “This is not the next Mick Jagger. But the lyrics did intrigue me.”

Krieger has noted that this is a person who sets the societal limit as to what we can say, how we can act, and that is something to be respected.

Bridging the gap between them and Morrison is Manzarek, seen as a highly skilled technician with a grand appreciation of Morrison’s poetic license. We know Morrison has gone too far in the moments when Manzarek objects, whether it’s halting play at a concert or confronting him at home.

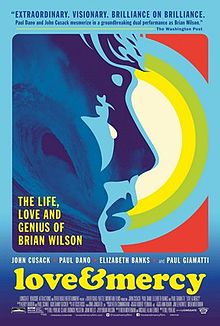

One typical difference between a great biopic and a great movie is the treatment of the artist’s signature song. The biopics such as “Ray” and “Walk the Line,” which were wonderful tributes though not particularly great movies, spend a fair amount of time building the drama to unveil the explosive hit.

Stone won’t be suckered by that. He masterfully crafts the origin of “Light My Fire” only partly as a glorious discovery. It is humbly offered by Krieger as a counterpart to Morrison’s exclusive song list, a signal the other band members can stand up to their frontman in the category of creative genius and will earn mutual respect. Kilmer is pitch-perfect here, subtly showing Morrison’s ability to bring life to a simple work. The song is not grandly improvised but merely sketched out in a little beach house, members singing off-key. This is good stuff but still a low-budget, skeptical, fickle operation. “I like it, it sounds like The Byrds, though, man. But I like it,” Densmore says.

Stone makes a choice — his Morrison could be a spoiled rock star, lucky to be here, having too much fun and taking full advantage of all of the largesse. Or he could be a troubled genius, haunted by tragic visions, plagued by addiction, Dionysus operating on another plane from mortals who don’t quite get it. The truth is all of the above. The latter makes the best movie. This is Stone’s major risk, the dealbreaker for too many critics. They do not want to see two hours of this self-pitying rock star ruining himself.

Kilmer’s Morrison is completely in sync with Stone. He is and was an actor of greater stature than his co-stars who knows where he stands in Stone’s eyes and in the eyes of the band’s characters. Jim Morrison was likely the biggest rock star America will ever know. Certainly there are other contenders, but Elvis was a bit premature, restrained by the Eisenhower era, and faded into caricature; Mick Jagger was British and was, to his credit, as motivated by the music as the performance. And neither died in his prime.

Morrison as a child and teen grew up around the country as a military brat, even attending a Florida community college and Florida State University, but spent formative years in Southern California, the hippest land in the world, so hip that everyone there is too cool to say so. He wore leather pants, flaunted a mane of hair, taunted police and posed barechested for photos. And the music he performed? Pretty good. Kilmer does receive high regard from critics in the impersonation. Some say he magnificently resembles Jim Morrison, but their looks are not a perfect match. His singing is more impressive, as is the body language not only on stage (Paula Abdul is credited as Kilmer’s choreographer) but in the way he deals with his friends. “I’m OK with being around you,” he conveys, “but you can’t share my stage.”

The women he spends time with are very telling. Never do Kilmer and Stone suggest Morrison would be happy singing “Light My Fire” for the girls and indulging in them afterwards (even though it certainly could be inferred he pursued that); instead he is extraordinarily high-maintenance, requiring rare women who can somehow push his buttons. Here is where Manzarek and many critics seem decidedly off-target; it’s not about the authenticity of the real person, but the authenticity of the character.

Morrison was probably not a great poet and perhaps not among the most elite circle of greatest rock singers. His off-the-chart skill was the way he could stand on a stage and belt out a rock song, like virtually no other human being. Must a person be a little crazy to reach the heights of Jim Morrison? Stone seems to argue, yes. Whatever it is about Morrison that ultimately would mesmerize a crowd and make women scream like few if any others also drives him to the bottle. The point of view could be that substance abuse ruined a pristine band, or, much more controversially, that whatever brings substance abuse fueled an otherwise lackluster band. Stone doesn’t seem comfortable with either option and apparently believes it’s somewhere in between. He clearly sees more than just alcohol as Morrison’s downfall, citing the lack of support from the music community when Morrison was put on trial in Miami. The inclinations that made Jim Morrison the greatest American rock star also caused his downfall.

“The Doors,” like Bob Fosse’s 1974 “Lenny,” suggests boundaries for even the most cutting-edge celebrities. It could be inferred from each film that the entertainment community will support shock but not arrest. Perhaps they agree too literally with Jim Morrison and Lenny Bruce that their arrests can’t be taken seriously. Each, however, is humiliated, standing virtually alone against motivated prosecution, uncomfortable and ultimately defeated in this forum.

Music appears to be no higher than Morrison’s third interest. Poetry is certainly tops, then perhaps philosophy or filmmaking. The nice thing about poetry, if it’s not particularly good, it still might make for effective song lyrics. Did Morrison intend to be a success, or did it merely engulf him? In scenes on the beach, he seems to take his cue from Manzarek. The songs are deemed good, so he’ll agree to form a band he’ll obviously come to dominate.

Stone presents the concerts as mostly unsatisfying, even though everyone connected to the band and film believes they were often electrifying. Failing to deliver just one untainted, majestic concert moment is one of Stone’s biggest flaws. Concerts are not shown as glorious events, but exaggerated poetry slams. Fans are heard clamoring during every performance, “C’mon Jim, sing ‘Light My Fire’,” and the implication is that they were denied. As the shows progress from L.A. clubs to East Coast arenas, we see an artist gradually toeing the line and then crossing it, from crudely discussing the Oedipus complex to taunting police to apparently exposing himself and attempting to incite a riot. The dubious Miami show seems like Morrison will make it resemble the Playboy bunny performance in “Apocalypse Now,” but this time, the crowd isn’t allowed to go hanging on the chopper. Stone does deftly handle the alleged exposure — the world of a broken person is whirling around, and we’re not really sure what we’re seeing.

Warhol is referenced at least twice, first when Morrison’s UCLA film class is evaluating his work. Later, after Sullivan, the band parties with Warhol. Morrison wants to stay; the others are eager to leave. Densmore, ever the pro, cites a big gig the next day. Manzarek implores, “C’mon Jim, this isn’t our scene, man. These people are vampires.” This is perhaps Kilmer’s greatest sequence, where he strides through a roomful of offbeat celebrity almost as a giant, taller than other characters, before getting his meeting with Warhol. Here Morrison is the shallowest of artists but the rarest kind of human being, in awe of no one. Morrison removes Warhol’s glasses, in a move that first seems a sort of sexual staredown but feels more like an examination — what’s really inside there? Warhol presents Morrison with a phone. “Now you can talk to God,” Warhol says, but moments later, a wasted Morrison is handing the phone to a homeless person in the street, off to an elevator rendezvous with a blonde groupie that reaches a disturbingly sad conclusion when Courson discovers the pair, only to hear a wicked Morrison laugh.

Stone makes several effective references to impotence, clearly a subject open to debate, as the ultimate grounding of Dionysus — a man who made women swoon perhaps like no other was often unable to consummate with them. This makes for some prolonged bedroom scenes that require patience. More visually effective is the bottle. Manzarek has complained about this, and in terms of accuracy he is likely correct, Morrison probably wasn’t carrying around booze everywhere he went. But there is certainly truth here; Morrison got into trouble more than once because of drinking. This is a visual crutch, but an effective one, for Stone, who would find it easier to depict someone under the influence by putting a bottle in his hand than a pill or acid in his pocket.

Famed film critic Roger Ebert, in a belittling 2.5-star review, says, “Watching the movie is like being stuck in a bar with an obnoxious drunk, when you're not drinking.” Referring to the graffiti-laced Paris grave site, he adds, “Even in death, Jim Morrison is no fun to be around.” A clever reference, though one that understates Stone’s majestic journey through the cemetery to the sounds of a synthesizer that strikes exactly the right chord.

Caryn James in an equally disdainful New York Times review said, “it demands an audience already as enamored of Morrison as the director is.”

Is Stone guilty of idolatry? Jim Morrison mattered only because of the way he could belt out a rock song. But oh, what a way that was. The Doors were going to be good. The catalog remains a staple of classic rock stations to this day. Overrated? Yes, but be careful ... “Light My Fire,” absurdly catchy, just a couple stanzas, yet unforgettable the moment you hear it. Stone appreciates that and sees greater value at least partly realized in his film, the rock god, the poet, the foursome that brought “The End” to “Apocalypse Now.”

“I wish in my heart, I wish he could’ve lived to be an older age so he could’ve appreciated what other people have come to appreciate,” Stone says.

Morrison, of course a filmmaker himself, might give Stone’s picture higher marks than most. He would see an imperfect biography elevated by the perfect star. Kilmer’s Morrison is handsome, magnetic, absurdly confident, with stunning credentials he never boasts of, and never for a moment thinking he needs to sober up. This landmark portrayal somehow failed to catch on with Hollywood, which instead awarded the best actor Oscar to Anthony Hopkins (for limited scenes in “The Silence of the Lambs”) and extended nominations to Warren Beatty (“Bugsy”), Robert De Niro (“Cape Fear”), Robin Williams (“The Fisher King”) and Nick Nolte (“The Prince of Tides”). Popularity might’ve been a factor; “The Doors” ranked 39th in gross in 1991 while all five of those competing films were higher.

One way Stone illustrates the band’s tenuous but unbreakable ties is in a well-written encounter after an L.A. show. A sleazy promoter first talks to the other three, then Morrison, suggesting to each they consider parting ways. “We’ll have a band meeting on it,” Manzarek says. “We do everything unanimously, or we don’t do it.”

“The musketeers. I’m touched,” the promoter says, using a beautifully contradictive term of a group that stood together, but as a trio.

That scene is not the only time it is suggested that Morrison would be better off leaving the band behind. In a final gathering at Manzarek’s home, a paunchy, bearded, nearly defeated Morrison convenes with The Doors for the last time, for a casual group self-assessment. Densmore admits he’ll miss the frontman, and Krieger says, “We had moments on stage that no one will ever f-----’ know.” Kilmer’s finest moments occur in this scene, where he paces aloof from the others, retaining a swagger, humorously jeers in Densmore’s face, but nevertheless allows the drummer a light punch to the gut. And so there is this important line from Densmore about “L.A. Woman,” the last work the Morrison Doors did together: “It’s the best album since ‘Days,’ man.”

Morrison hurt people by straying. He never completely let the group down. Not all the film’s messages are clear, but the strongest is one of loyalty: Even America’s biggest rock star wasn’t too big for his own band.

3.5 stars

(October 2009)

“The Doors” (1991)

Starring Val Kilmer as Jim Morrison ♦ Meg Ryan as Pamela Courson ♦ Kyle MacLachlan as Ray Manzarek ♦ Frank Whaley as Robby Krieger ♦ Kevin Dillon as John Densmore ♦ Michael Wincott as Paul Rothchild ♦ Michael Madsen as Tom Baker ♦ Josh Evans as Bill Siddons ♦ Dennis Burkley as Dog ♦ Billy Idol as Cat ♦ Kathleen Quinlan as Patricia Kennealy ♦ John Densmore as Engineer - Last Session ♦ Gretchen Becker as Mom ♦ Jerry Sturm as Dad ♦ Sean Stone as Young Jim ♦ Kendall Deichen as Little Sister ♦ Floyd Red Crow Westerman as Shaman ♦ Rion Hunter as Indian in Desert ♦ Wes Studi as Indian in Desert ♦ Steve Reevis as Indian in Desert ♦ Bernie Telsey as Young Man with Pam ♦ Bruce MacVittie as UCLA Student ♦ Andrew Lauer as UCLA Student ♦ Harmonica Fats as Blues Singer on Venice Boardwalk ♦ Kelly Ann Hu as Dorothy ♦ John T. Forristal III as Bouncer ♦ Josie Bisset as Robby Krieger’s Girlfriend ♦ Fiona as Fog Groupie ♦ Bob Lupone as Music Manager ♦ Paul Rothchild as Music Manager’s Sidekick ♦ John Capodice as Jerry ♦ Eric Burden as Backstage Manager ♦ Nellie Red Owl as Old Crone ♦ Victoria Seeger as Whiskey Girl ♦ Debbie Mazar as Whiskey Girl ♦ Jacqui Bell as Whiskey Girl ♦ Sergio Premoli as Patron at The Whiskey ♦ Mark Moses as Jac Holzman ♦ Frank Military as Bruce Botnick ♦ Debbie Falconer as John Densmore’s Girlfriend ♦ Michele Bronson as New York Groupie ♦ Will Jordan as Ed Sullivan ♦ Sam Whipple as Sullivan's Producer ♦ Charlie Spradling as CBS Girl Backstage ♦ Lisa Edelstein as Makeup Artist ♦ Erik Dellems as Hairdresser at the Sullivan Show ♦ Mimi Rogers as Magazine Photographer ♦ Jennifer Rubin as Edie ♦ Paul Williams as Warhol PR ♦ Kristina Hare as Partygoer ♦ Costas Mandylor as Italian Count ♦ Christina Fulton as Nico ♦ Crispin Glover as Andy Warhol ♦ Bernt Kuhlman as Warhol Eurosnob ♦ Claire Stansfield as Warhol Eurosnob ♦ Karina Lombard as Warhol Actress ♦ Christopher Lawford as New York Journalist ♦ Dani Klein as New York Journalist ♦ Laura Esterman as New York Journalist ♦ Deborah Lupard as New York Journalist ♦ Ashley Stone as New York Journalist ♦ Richard Rifkin as New York Journalist (as Richard B. Rifkin) ♦ Chris Boyle as New York Journalist ♦ Adrian Scott as New York Journalist ♦ Bill Graham as New Haven Promoter ♦ Titus Welliver as Macing Cop ♦ Eagle Eye Cherry as Roadie ♦ David Allen Brooks as Roadie ♦ Danny Sullivan as New Haven Cop ♦ Stanley White as New Haven Cop ♦ Frank Girardeau as Police Lieutenant ♦ Bonnie Bramlett as Bartender ♦ Rodney A. Grant as Patron at Barney's (as Rodney Grant) ♦ Brad von Beltz as Hippie at Party (as Brad Von Beltz) ♦ Hawthorne James as Chuck Vincent ♦ Csynbidium as Girl in Car ♦ Cirsten Weldon as Girl in Car ♦ Patricia Kennealy as Wicca Priestess ♦ Davidson Thomson as High Priest ♦ Leonard Crow Dog as Indian at the Outdoor Concert ♦ Carmella Runnels as Indian at the Outdoor Concert ♦ Keith Reddin as Miami Journalist ♦ Billy Vera as Miami Promoter ♦ Allan Graf as Miami Cop ♦ Jack McGee as Miami Cop ♦ Alan Manson as Judge (as Allen Manson) ♦ William Kunstler as Lawyer (as Bill Kunstler) ♦ Peter Crombie as Associate Lawyer ♦ Robert Marshall as Prosecutor (as Bob Marshall) ♦ Annie McEnroe as Secretary ♦ Tudor Sherrard as Office Publicist ♦ Jad Mager as Office P.A. ♦ Kelly Leach as Birthday Girl ♦ Richard Rutowski ♦ Theresa Bell as Hippie Girl ♦ Cindi Braun as Hippie Girl ♦ Arthur Bremer as Himself ♦ M.C. Brennan as Stray Hippie ♦ Kathy Brolly as Hippie Chick ♦ Tay Brooks as Warhol guest ♦ William Calley as Himself ♦ Bob Casper as Sailor / Concert Goer ♦ Don ‘Tex’ Clark as Army Soldier ♦ Bret Culpepper as Motor Officer ♦ Efrain Denson as Audience Member ♦ Tim Duquette as UCLA Film Student ♦ John Louis Fischer as Trick's Friend ♦ Phil Fondacaro as Man at Birthday Party ♦ Ben Gardiner as Guru ♦ Adolf Hitler as Himself -in Speech ♦ Rich Hopkins as Hippie ♦ Ethel Kennedy as Herself ♦ Robert F. Kennedy as Himself ♦ Martin Luther King as Himself ♦ Charles Manson as Himself ♦ Troy Martin as Music lawyer ♦ Kim Meredith as Reporter ♦ Richard Nixon as Himself ♦ Randall Oliver as Groupie ♦ Dian Van Patten as Concert Hippie ♦ Shannon Ratigan as Soundman ♦ Michael Reardon as Roadie ♦ Jennifer Robertson as Hippie ♦ Heidi Schooler as New Haven Reporter ♦ Ron Severdia as Roadie ♦ Oliver Stone as UCLA Film Professor ♦ Jennifer Tilly as Okie Girl ♦ Mariana Tosca as Groupie ♦ John Trujillo as Hippie ♦ George Wallace as Himself

Directed by: Oliver Stone

Written by: Randall Jahnson

Written by: Oliver Stone

Producer: Bill Graham

Producer: Sasha Harari

Producer: A. Kitman Ho

Executive producer: Nicholas Clainos

Executive producer: Brian Grazer

Executive producer: Mario Kassar

Associate producer: Joseph Reidy

Associate producer: Clayton Townsend

Executive producer: Ron Howard

Bay producer EPK: Catherine Meyers

Cinematography: Robert Richardson

Editing: David Brenner ♦ Joe Hutshing

Casting: Risa Bramon ♦ Billy Hopkins

Production design: Barbara Ling

Art direction: Larry Fulton

Set decoration: Cricket Rowland

Costume design: Marlene Stewart

Post-production supervisor: Bill Brown

Unit production manager: Helen Pollak

Makeup and hair: Ron Berkeley ♦ Lynda Gurasich ♦ Ken Diaz ♦ Tom Case ♦ John Norin Barbara Lorenz ♦ Carol Meikle

Stunts: William Burton ♦ Webster Whinery ♦ Courtney Pakiz ♦ John Borland ♦ Bobby Andrew Burns ♦ Hal Burton ♦ William H. Burton Jr. ♦ Chris Durand ♦ Steve Geray ♦ Randy Hall ♦ Tabby Hanson ♦ Terry Jackson ♦ Steve Kelso ♦ George Marshall Ruge ♦ Dennis Scott ♦ Doc D. Charbonneau) ♦ Alisa Christensen ♦ Diana Cuevas ♦ Dane Farwell ♦ Shawn Lane ♦ Kevin Larson ♦ Tim Meredith ♦ Denney Pierce ♦ Pat Romano ♦ Frank Torres

Special thanks: The Doors

In memory of: Rocco Viglietta