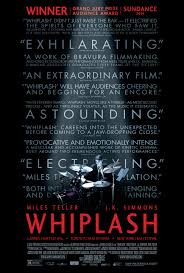

The jazz stinger: Studying

under Terence Fletcher

will give you ‘Whiplash’

No, Terence Fletcher would not keep his job at the best music school in the country after repeatedly slapping a student.

Most can suspend disbelief and buy what needs to be bought: He’s so good, so important that none of his students will complain, and everyone else will remain oblivious to what occurs in this tiny universe.

“Whiplash,” which thrives exclusively on this stirring portrayal, does not concern itself with modern classroom ethics, or even the concept of learning, but with an infrequent cinematic theme — perfection. Its two leading characters implicitly agree that something that can’t be done flawlessly isn’t worth doing at all.

The film’s choice of battleground is its biggest twist. Who would have thought that jazz is far more science than art, that its performers can be ranked like college football teams, that certain perfections can be realized even if only detectable by a select few. An implication of “Whiplash” is that, while what John, Paul, George and Ringo managed to do was fun and influential, the gold standard of music achievement rests within the walls of Fletcher’s rehearsal room, a venue somehow more grim than a morgue.

However debatable that is, because this is a film about music, it has a distinct advantage over professorial studies such as “The Paper Chase” and “Good Will Hunting,” where the student’s development (aside from meeting women) is limited to unseen essays and proofs. In “Whiplash” we can actually hear the education. Where Mr. Hart is scribbling an outline, Andrew Neiman is pounding his hands into blood.

Unquestionably, Fletcher is in charge of the classroom. He is not in charge of the drama. There, he’s only an equal partner. With incredible subtlety, “Whiplash” suggests that Fletcher is just as vulnerable as his prized student. Poor Andrew doesn’t realize: Fletcher needs him.

Initially, we find Fletcher ruthless. Notice how little attention he pays to most of the members of his ensemble. Either he has deemed them incapable of the greatness he covets or unresponsive to the button-pushing he thrives on. But is it a reach to conclude he is simply ... bored?

“Whiplash” can be categorized among a fraternity of seemingly unrelated films (“The Bling Ring” was a recent gem) depicting this underrated scourge of humankind. Progress has brought us so much as to leave us a void that is often filled not by even higher aspirations, but our worst tendencies. By historical standards, it’s too easy to achieve a roof over our heads or food on the table ... or a faculty position.

Despite his elite status, Fletcher seems to take little satisfaction in anything besides terrorizing people less than half his age. There is no indication he is under stress from a competitive threat; he points out that his bands regularly win a select competition. He defends his approach this way: He is determined to find the next Charlie Parker or Buddy Rich, and in exchange for the possibility of pulling this off, he’s not going to apologize for whatever means are necessary.

Andrew Neiman is definitely not bored. He instantly finds himself seeking Fletcher’s approval. Presumably he is singled out because Fletcher senses in him a potential difference-maker. Played unevenly by Miles Teller, who was in his mid-20s during filming, Andrew noticeably appears younger than his fellow bandmates. Here is another implication, that as with supermodel magazine covers or the NBA Draft, the elites are discovered by age 20.

Teller wavers on the critical element of Andrew’s confidence level. Andrew does not realize that in the real world, Fletcher’s silly rules are meaningless and that if Andrew is as great as he aspires to be, others will figure it out. Nor does he question whether Parker or Rich could meet Fletcher’s outrageous standards. (“Whiplash” actually was a composition of Hank Levy.) Yet instead of jamming with friends or classmates (who barely speak to each other), Andrew is shown repeatedly in solitary competition with himself, awaiting Fletcher’s judgment. In a fairly clumsy dinner-table discussion that is not one of the film’s strengths, Andrew scoffs at high-caliber football players who are below NFL standards.

J.K. Simmons, long one of the country’s most appealing actors, overachieves in ways Andrew wouldn’t dream. This is an occasion when the term “one-note performance” is not a slur. Does anyone wonder if an individual such as this has a wife and/or kids? Where he went to school, what kind of car he drives or whether he attends religious services? None of that character analysis matters. He is relentlessly Gordon Gekko or Raymond Babbitt or Ben Sanderson, an individual we all encounter at some point whom we admire on some level, want to succeed with, and struggle to deal with. It is no accident that those other three characters produced Oscars.

Simmons, in outstanding physical shape and clothed equally well for artistic direction and intimidation, understands in this picture that his vote is the only one that counts. His expressions and body language crown the winners and (more typically) scorn the losers. Among the challenges of “Whiplash” is the audience’s capacity to discern this level of music. Which drummer is doing better? We take our cues less from our ear than from the corners of Simmons’ mouth.

Simmons easily compensates for two notable flaws of the film. Too much is shot within the bland walls of Fletcher’s rehearsal room. Yes, it reverberates with life, but Sharone Meir’s images, unlike Andrew, are much less confident off-stage. Then there is Andrew’s too-easy caving to the requests of a lawyer. The script owes it to its audience to provide a more convincing impetus for Andrew’s decision.

Too often, supporting characters get in the way. Paul Reiser, as Andrew’s father, seems to have wandered onto the set expecting a sitcom. Melissa Benoist as Nicole gives us little reason to wish that Andrew was less focused on sounds than sights.

We could use more of Nate Lang’s Carl and Austin Stowell’s Ryan, who actually are pitch-perfect as the pawns on Fletcher’s radar screen.

When a slap occurs in a movie, a line is crossed, whether it be Patton in Italy or Bud Davis at Gilley’s club. Accepting the artistic license of “Whiplash,” Simmons has reset the boundaries of academic subordination. Professor Kingsfield in “The Paper Chase” is austere and aloof; his approval amounts to making it. Professor Gerald Lambeau in “Good Will Hunting” is an uppity cheerleader; his approval amounts to nothing. It is also in “Good Will Hunting” where another instructor, Robin Williams’ Sean Maguire, grabs a student by the throat. Fletcher clearly would have no qualms about doing that, in the unlikely event he would ever need to.

Teller fails to demonstrate Andrew’s end game. Is he looking for jobs, gigs, or press acclaim? We see that Andrew has trouble with the conventions of his craft. He is not wedded to sheet music in any way, to the extreme detriment of a clueless rival who fails to notice this. Andrew, like the greats, seems to have instinct. Yet it is never clear how Andrew expects Fletcher to elevate him to the status of Parker, who did not graduate from high school. Some viewers will be well familiar with Parker’s catalogue. Most will not be able to name when he lived or what instrument he played or his significant contribution to the art form. A few may wonder why Fletcher and Andrew don’t just form a rock band and have some fun.

There’s a less-appealing, alternate theory to “Whiplash.” What if Fletcher is not interested in the music, but the torture ... and that Andrew’s skills are incidental to the fact that he’s simply the only one this semester who will go along with this shtick in the way Fletcher enjoys. We learn that Fletcher is capable of lying. (In fact, can we really be certain he lost his job so quickly? Might he actually be on sabbatical, baiting Andrew with a guilt trip?) What if the whole next-Charlie-Parker thing is a lie, and what we have here is a simple, overgrown bullying tale.

Writer and director Damien Chazelle, who just turned 30 and has a 2009 musical about a jazz trumpeter to his credit, delivers echoes of a long-ago work, David Lean’s “The Bridge on the River Kwai,” in which a fanatical process begins to supersede the apparent goal. Chazelle’s stanzas need work. His maestro is more than enough.

4 stars

(January 2015)

“Whiplash” (2014)

Starring Miles Teller as Andrew ♦

J.K. Simmons as Fletcher ♦

Paul Reiser as Jim ♦

Melissa Benoist as Nicole ♦

Austin Stowell as Ryan ♦

Nate Lang as Carl ♦

Chris Mulkey as Uncle Frank ♦

Damon Gupton as Mr. Kramer ♦

Suanne Spoke as Aunt Emma ♦

Max Kasch as Dorm Neighbor ♦

Charlie Ian as Dustin ♦

Jayson Blair as Travis ♦

Kofi Siriboe as Bassist (Nassau) ♦

Kavita Patil as Assistant - Sophie ♦

C.J. Vana as Metz ♦

Tarik Lowe as Pianist (Studio Band) ♦

Tyler Kimball as Saxophonist #2 (Studio Band) ♦

Rogelio Douglas Jr. as Trumpeter #1 (Studio Band) ♦

Adrian Burks as Trumpeter #2 (Studio Band) ♦

Calvin Winbush as Saxophonist (Studio Band) ♦

Joseph Bruno as Technician (Overbrook) - Mike ♦

Michael D. Cohen as Stage Hand (Overbrook) ♦

Jocelyn Ayanna as Passerby (Bus Station) ♦

Keenan Henson as Truck Driver ♦

Janet Hoskins as Passerby (Dunellen) ♦

April Grace as Rachel Bornholdt ♦

Clifton ‘Fou Fou’ Eddie as Drummer (Quartet) ♦

Marcus Henderson as Bassist (JVC) ♦

Tony Baker as Stage Hand (Carnegie Hall) ♦

Henry G. Sanders as Red Henderson ♦

Sam Campisi as Andrew (8 years old) ♦

Jimmie Kirkpatrick as Nassau Trumpeter #2 ♦

Keenan Allen as Studio Core Member #1 ♦

Ayinde Vaughan as Studio Core Member #2 ♦

Shai Golan as Studio Core Member #3 ♦

Yancey Wells as Studio Core Member #4 ♦

Candace Roberge as Student #1 ♦

Krista Kilber as Student #2

Directed by: Damien Chazelle

Written by: Damien Chazelle

Producer: Jason Blum

Producer: Helen Estabrook

Producer: David Lancaster

Producer: Michel Litvak

Co-producer: Nicholas Britell

Co-producer: Garrick Dion

Co-producer: Sarah Potts

Co-producer: Stephanie Wilcox

Line producer: Mark D. Katchur

Associate producer: Phillip Dawe

Executive producer: Gary Michael Walters

Executive producer: Couper Samuelson

Executive producer: Jason Reitman

Executive producer: Jeanette Volturno-Brill

Music: Justin Hurwitz

Cinematography: Sharone Meir

Editing: Tom Cross

Casting: Terri Taylor

Production design: Melanie Paizis-Jones

Art direction: Hunter Brown

Set decoration: Karuna Karmarkar

Costume design: Lisa Norcia

Makeup and hair: Tobe West, Nacoma Whobrey, Traci E. Smithe, Heather Plott, David Larson

Stunts: Mark Riccardi, Kevin Patrick Burke, Brady Romberg, Chester Tripp, Steven Stone