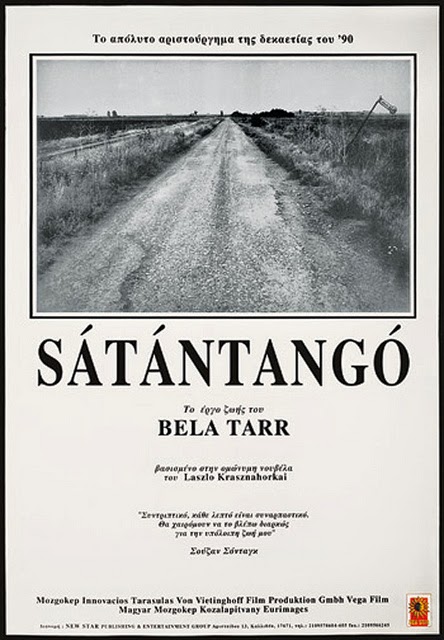

Time is put to the test in

Béla Tarr’s ‘Sátántangó’

“I despise stories, as they mislead people into believing that something has happened. In fact, nothing really happens as we flee from one condition to another ... All that remains is time. This is probably the only thing that’s still genuine — time itself; the years, days, hours, minutes and seconds.” — Béla Tarr, quoted by Roger Ebert, 2007

The circumstances of the above quote are unclear. Roger Ebert does not exactly indicate that Béla Tarr said this to him directly, but neither does he state when or where the comment was made. The first two sentences, if true, figure to undermine virtually every film ever made. Regardless, time does matter, which is what makes Tarr’s 432-minute “Sátántangó” a significant and curious film.

Hardly seen in North America, “Sátántangó” is acclaimed worldwide by cinephiles. Little has even been written about it in the United States (though it’s fair to note that it premiered before most humans had an Internet connection). Snippets of reviews are posted at the popular rottentomatoes.com, but most of the links are dead. The film is most likely to be noticed by Americans as tied for 35th in the most recent once-a-decade poll by Britain’s Sight & Sound of the greatest films of all time. Susan Sontag in an essay praised Tarr and said she could watch “Sátántangó” once a year. The critic Jonathan Rosenbaum in 1996 called the film “in many ways my favorite film of the ’90s.” Prior to a 2006 screening, Manohla Dargis in the New York Times wrote that the film “is never less than mesmerizing.” A 2012 article in the Los Angeles Times dubbed the film a “herculean achievement and one of the decade’s masterworks.”

Despite such lofty recognition, not everyone was sold. Ebert apparently never reviewed it and perhaps never saw it. In a 2007 review of another Tarr film, “Werckmeister Harmonies,” which owns a position in Ebert’s Great Movies list, Ebert cites the length of “Satantango” as precluding himself and many others from watching, and that “Werckmeister” became his first Tarr screening only after obtaining the DVD through Facets Multimedia. “For all of my time on the festival circuit, I had never seen one of his films until this one,” he writes, and, “When you’re at a festival and seeing one film means missing four others, you tend to take the path of least resistance.”

The 1994 observations by the New York Times’ Janet Maslin serve more as a warning than review, calling the film a “bleak, imposing cinematic experiment” that “sometimes lives up to great expectations, but its unevenness allows many questions to creep in.” Maslin cautions that “a good night’s sleep” before a screening is a “must.”

Debate about “Sátántangó” must be whether Tarr has created seminal art ... or simply completed a project that other filmmakers, for quite valid reasons, don’t bother to try.

It is virtually impossible to read an article about Tarr and not notice a comparison to Andrei Tarkovsky, the Soviet director whose pacing, colors and shots through doors (particularly in the spectacular 1979 “Stalker”) established a Merlot Movie genre. But much of Tarr’s approach in “Sátántangó” relies on tried-and-true cinematic devices. He knows that rain, particularly steady rain, photographs and sounds very convincing, and that fog looks good, that dystopia is more dystopian in black and white, that there is, for whatever reason, drama in walking in mud; he likes the sound of pouring alcohol from a large bottle into a small glass; he knows that cute animals grab our attention in disproportionate ways and uses this to devastating effect, and the same for children; with both, he will cross lines that few filmmakers approach.

And he knows his protagonists should be more handsome, taller, and more stylish than the rest and of course walk in the middle in groups of 3.

The effectiveness of those techniques aside, the secret of “Sátántangó” is the notion of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts, that the viewer appreciation stems not from a notable scene or approach but endless immersion in the surroundings, the way a sip of wine may not seem like much until you’ve had half of the bottle.

“Sátántangó,” translated easily as “Satan’s Tango,” is divided into 12 chapters, which are supposed to represent the novel’s tango format of 6 steps forward and 6 back. Where and when does the film take place? In Hungarian language, it was released in 1994, perfect timing for a critique on European communism. But the novel, by László Krasznahorkai, was finished in the mid-1980s, and Tarr struggled for years to get the film made. It appears to be present day, but it’s what’s not in the film that suggests this could also be taking place decades earlier. No one in this crumbling farm community watches television or listens to the radio, hardly anyone drives a vehicle, electricity appears to be a luxury. The terrain seems to resemble the American Dakotas. At one point, a character reflects on being Hungarian, but the group seems less connected to the rest of their country than Matt Damon is at his Mars colony in “The Martian.” A review of Sátántangó the book in the New York Times suggests readers are trapped “in a bubble of time.”

Hungary, a nation of 10 million, occupies minimal real estate in the U.S. consciousness. Ask Americans what they know about it and probably at most, 3 things come to mind; the 1956 Soviet invasion; baseball’s colorful “Mad Hungarian” Al Hrabosky and perhaps even Allen Sherman’s Hungarian Goulash routine, all of those references no doubt fading fast by the generation.

Internationally famous Hungarians include Rubik's Cube inventor Ernő Rubik, composers Béla Bartók and Franz Liszt and actor Bela Lugosi. Those with Jewish ancestry include financier George Soros, former Intel chairman Andrew Grove, the Gabor sisters, director Michael Curtiz and Erik Weisz (that would be Harry Houdini). Enmeshed in various alliances for centuries, Hungary was something of an Eastern European beacon post-World War II: According to the Hungary Wikipedia page, the country was seen as “the happiest barrack” in the Soviet bloc and presently ranks 20th in quality of life worldwide.

While the “Sátántangó” landscape is bleak, the villagers possess a curious mutual respect. They will lie, cheat, spy on and scheme against each other, but in the way that siblings or cousins do. There are no “Deliverance” moments here. Each character seems to be a link in the survival chain, almost like the cast in television’s “Gilligan’s Island.” Tarr identifies them by differing coats and hats that stand out for their plainness. A girl looks like a boy. Despite the hardship economy, many of these characters are overweight. They are not destitute but wanting, evidenced by a party scene that is driven home by Tarr similar to the way Michael Cimino portrayed the wedding in “The Deer Hunter,” an endless, short clip of an accordion tune while the stationary camera shows reckless dancing occasionally veering offscreen. The “Sátántangó” villagers are not particularly sympathetic until at least halfway through the film or later, when they are moved by the most genuine sentiments to uproot themselves for the sake of a dubious and mysterious initiative.

Tarr cleverly alternates between giving the characters, then the audience, more knowledge about the protagonist, Irimiás. The villagers’ reaction to his apparent sighting suggest he is a mysterious man to take seriously. This is backstory that somehow, in a 7-hour film, will remain unknown. In such a small town, lack of information on his current whereabouts is remarkable. But his timing proves perfect, arriving at a moment of despair and unleashing a speech that Tarr depicts similarly to Joan of Arc’s declarations in Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc” (though Irimiás is most certainly playing offense, not defense, in his remarks). Irimiás sounds supremely confident about knowing what to do. He declares the group can start a new operation but that it will take capital to succeed. Consumed by guilt, the others agree and start tossing in money. Why are the villagers susceptible to his scheme? Perhaps because he’s the only one who offers one. “Sátántangó” can be said to be a warning about overseas telemarketing scam artists who happen to connect with a 75-year-old Floridian whose spouse has passed away “and I don’t have anybody to talk to anymore.” The lone counterweight to Irimiás figures to be the ailing doctor, whom Roger Ebert would dub the “reliable observer” of the film. But the doctor limits his influence to just that, observing, and is unable to offer an opinion at a critical time.

The Wikipedia entry for “Sátántangó” indicates the film entertains the concept of nihilism. But it seems the characters are no different than human beings in declining companies, countries, families. Base instincts emerge. Standards are compromised and dreams melt into schemes in hopes of staying afloat. What these characters need is expansion of their outlook, the big picture, which for the “Sátántangó” villagers is unfortunately delivered by the wrong person.

“Sátántangó” is very much about change — massive change — and why we need it. The villagers are sitting on a failure. Then tragedy. They have the look of hardy figures, but they have been numbed into a sense of complacency that makes them susceptible to a charismatic figure while oblivious to well-meaning ambition.

Irimiás is portrayed by Mihály Víg, a longtime associate of Tarr’s who is perhaps more famous in Hungary as a composer. He provides a spellbinding score that sounds like it’s from a cheap organ and gains steam as Irimiás’ plot takes shape. Notice one reason why he is able to seduce the people. He is tall, the most handsome of the group, he wears black and the most stylish hat. The others tend to be pudgy, balding; they wear their coats and hats seemingly at all times. We know if Irimiás resembled Danny DeVito, his arrival would be met with much skepticism.

There are parallels in Víg’s arrival to that of Warren Beatty in “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” but the two diverge in agenda, with McCabe proposing the buildout of the town to get ahead while Irimiás plots the destruction of it.

A few hours in, the drama of “Sátántangó” begins to gain traction. But just as the apparent climax unfolds in the last hour, motivation becomes all the more mysterious. After reaching the group’s purported destination, Irimiás is inclined to set up a different scheme involving weaponry, with a man who is a police official of some kind. That this meeting is kept secret from the others suggests their fate is sealed. At its most basic level, the implication is that Irimiás is turning in the group for some sort of anti-state activity in exchange for some benefit. But this is an era where the authorities are not so much feared but apparently negotiated with.

It is one thing for the villagers to believe that the stated plan, to restart a community from an empty building, is believable; somehow they are not dissuaded to hear from Irimiás that the plan has stalled and that to make it work, they must scatter around the country anonymously until hearing from him again.

A considerable amount of time is spent on the police officials editing Irimiás’ accounts of the people. For the benefit of viewers, this involves one character reading aloud what Irimiás has written and the other character editing the description out loud. They seem to take a small amount of pleasure in this tiny opening for creativity. The viewers are far more familiar with these people than the officials are, but the revised editions sound almost as if the authorities have been watching the entire movie. Nevertheless, to the officials, it’s just business, and they matter of factly close the cabinet file, another and perhaps final chapter in these individuals’ lives.

It’s commonplace for apocalyptic/dystopian material to elevate even the simplest human basics to gold; such is the case when Irimiás and his associate Petrina meet at Steigerwald’s and order drinks, then bean soup. “With ham,” Petrina says with an unusal assertiveness, and shortly after, we actually see Sátántangóans enjoying a meal.

Because of the film’s obscurity, it apparently escaped the attention of animal-rights advocates. Tarr includes scenes involving a cat that almost assuredly would never be shown in a commercial American film (or even a non-commercial one, as the filmmakers could risk prosecution). On this front, “Sátántangó” smashes through the cinematic envelope. “Apocalypse Now” could show a remote Filipino tribe slaughtering a water buffalo because it happened on foreign soil and was not illegal there and was, by official account, not ordered or requested by the filmmakers. “Killer of Sheep,” done by a college student, could show an American slaughterhouse because its operation was very much legal. It is considered an important stamp of approval for film credits to include “No animals were harmed” in the making of the picture (although the strength of that distinction has been called into question).

The “Satantango” cat scenes are counterproductive if not bogus. Rather than enhancing authenticity, they tangle it. Viewers are struck by emotions not within the film but that pierce the dramatic wall — “Did I just see a poor cat tortured? Please assure me it wasn’t real.” And even if it’s not real, is it right to ask a child actor to be part of this scene? In a 2001 interview, Tarr “insists” the cat was not harmed and became a family pet, the use of the word “insists” implying that the writer or Tarr senses skepticism toward this claim. One blogger declares this scene as “the one thing that hurt the film,” because even taking Tarr at his word, “I’m still troubled. And that’s the problem.”

Manohla Dargis in the New York Times wrote that, “Animal lovers beware,” because despite Tarr’s claim, the cat “is clearly in distress.”

Meanwhile, while Tarr insisted his cat treatment was not real, he freely admitted the cast indeed was intoxicated for the scenes of drunkenness. It’s remarkable how popular this bit of realism is. Actors can act like autistic savants (“Rain Man”) without being autistic savants, but they apparently can’t depict intoxication without being drunk. Oliver Stone told Charlie Sheen to stay up all night and get loaded for a scene in “Wall Street.” Wonder how hard it was to get the actor to oblige.

Making a film such as “Sátántangó,” it is no surprise Tarr has no interest in industry acclaim. “Sátántangó” was not in consideration for the Oscars’ best foreign-language film. Tarr indicates that the movie industry is “a f---ed-up business, which is not my business,” and, ”It’s all a kindergarten.” He’s hardly the first to believe that. He is one of the few to make a 7-hour black-and-white film in defiance of it.

In 2011, Tarr’s “The Turin Horse” was Hungary’s entry for foreign-language Oscar; it was not nominated. Despite Tarr’s accomplishments, Hungary’s “political and artistic establishment has often kept him at arm’s length.”

Some things in life easily lend themselves to trial and error. Moviemaking is not one of them. Could “Sátántangó” succeed better at 2 hours? 5? 11? A filmmaker only gets one chance. It is not a matter of re-editing. In each case, it’s a different movie, different agendas; a 2-hour version of “Sátántangó” would have to be shot before or after the version we know, the actors would be at different ages, the priority from the beginning of the production different. There is a budget that will pay for so much filming. Actors and filmmakers have other commitments and deadlines. They must make a living. Filming locations aren’t always available. Point being, there is no possible way Béla Tarr could do 4 versions of “Sátántangó” at varying lengths to determine the most effective length. He is inspired by an idea, seeks financing, and acts upon it. Tarr is correct that time is genuine; he could’ve noted that it is steady, fixed and neither expandable nor shrinkable; once it’s gone, it’s gone, and then can resume, everything older than it previously was.

The same constraints exist for anyone reviewing “Sátántangó” or any film. Could they go for weeks, putting together 20,000 words on anything relevant to this work? Perhaps. But there are deadlines to meet, other responsibilities in their lives, and unwanted monotony from obsessing over a single project.

The flaw, perhaps the only one, in “Sátántangó” is the suggestion of it. If it is indeed one of the greatest films ever made, supporters need to explain why it should not be 9 hours. Here is a single motion picture, low budget, in black and white, a foreign language (for non-Hungarian viewers), about a bleak existence, to occupy pretty much your entire workday.

A lot of smart, open-minded, patient people — including cinemaphiles with impeccable credentials — will hear that description and decide it sounds “indulgent” or “pretentious.” Humans cannot unsee and rewind the clock. Welles and Hitchcock and Bergman and Renoir did masterworks in a far more agreeable amount of time. Every moment spent watching “Sátántangó” is a moment not spent watching, or doing, something else. Unfortunately, like all great art, it is missable. In a Catch-22 of artistic appreciation, we pick and choose never really knowing what we’re declining. For guidance or reassurance, we rely on the word of those who have seen it, or maybe the trailer, the poster, the description, or a gut feeling.

“Sátántangó” works. Maybe anyone could do it; Tarr did. Great films aren’t limited to their duration. They’re to be appreciated, considered, savored for hours, days, years afterwards. “Sátántangó” very much meets that definition. Those who don’t bother have a point too.

4 stars

(November 2017)

“Sátántangó” (1994)

Starring

Mihály Vig as Irimiás ♦

Dr. Putyi Horváth as Petrina ♦

László feLugossy as Schmidt ♦

Éva Almási Albert as Schmidtné ♦

János Derzsi as Kráner ♦

Irén Szajki as Kránerné ♦

Alfréd Járai as Halics ♦

Miklós Székely B. as Futaki ♦

Erzsébet Gaál as Halicsné ♦

György Barkó as Iskolaigazgató ♦

Zoltán Kamondi as Kocsmáros ♦

Barna Mihók as Kerekes ♦

Péter Dobai as Százados ♦

András Bodnár as Horgos Sanyi ♦

Erika Bók as Estike ♦

Peter Berling as Orvos ♦

Ica Bojár as Horgosné ♦

István Juhász as Kelemen ♦

Ferenc Kállai as Orvos (voice) ♦

Mihály Ráday as Narrator (voice) ♦

Gyula Pauer ♦

Ernõ Mihályi ♦

Mihály Kormos ♦

András Fekete ♦

Andor Simai ♦

Katalin Krizsánné Kovács ♦

Vilmosné Pataki ♦

Mária Borbély ♦

Kati Makrányi ♦

Zsuzsa Fodor ♦

Beatrix Jeszensky ♦

Rita Deák Varga ♦

Frigyes Hollósy ♦

Ágnes Kamondy ♦

Kína Vetõ ♦

Mia Santamaria ♦

József Kresinka

Directed by: Béla Tarr

Written by: László Krasznahorkai (novel)

Written by: Mihály Vig, Péter Dobai, Barna Mihók (story)

Written by: Béla Tarr, László Krasznahorkai (screenplay)

Producer: György Fehér

Producer: Joachim von Vietinghoff

Producer: Ruth Waldburger

Music: Mihály Vig

Cinematography: Gábor Medvigy

Production design: Sándor Kállay

Set decoration: Sándor Katona, Béla Zsolt Tóth

Editing: Ágnes Hranitzky

Costumes: János Breckl, Gyula Pauer

Special effects: Péter Pásztorfi

Dedicated to: Alf Bold

Special thanks: Tibor Dimény

Special thanks: Gábor Koncz

Special thanks: Marcell Merza

Special thanks: Ernõ Mihályi

Special thanks: Tibor Orosz

Special thanks: Ulrich Ströhle

Special thanks: Sándor Sõth

Special thanks: Gábor Téni

Special thanks: Karin Wegmann

Special thanks: Katalin Óvári

With the support of: Klári Téni

With the support of: László Vincze