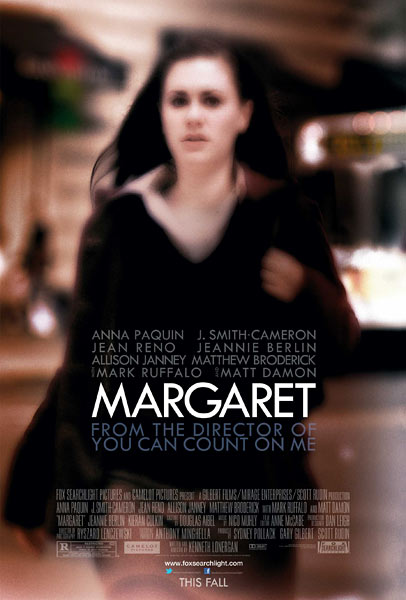

‘Margaret’: A crash course

in a grown-up world

Lisa’s struggling with Geometry.

But she’s got a Ph.D. in Manipulation.

Kenneth Lonergan’s “Margaret” is many things, maybe most significantly an indictment of higher education. The only high school coursework Lisa’s going to master is sexuality, her instructors not just dispensers of but part of the curriculum.

Sometimes an actress finds a perfect role in an imperfect film. Anna Paquin was in her early 20s during filming but bears a remarkable resemblance at times to Jennifer Jason Leigh in “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.” Not the eyes but the mouth. Paquin’s Lisa is far less innocent and far more dangerous. At times, the camera will catch her at gorgeously vulnerable angles, maybe moments of doubt, such as when she declares Shakespeare “seems pretty self-evident to me.” A tornado of intensity, she can carry the film only so far before the script runs out on her.

“Margaret” took a dubious path to the theater. That is a red flag. Lonergan’s widely anticipated follow-up to his mesmerizing “You Can Count on Me,” the film was completed in 2005 before a legal dispute between Lonergan and one producer, Gary Gilbert, delayed its release for years. Gilbert deemed Lonergan’s 2½-hour cut “incoherent” and ordered a two-hour version. Eventually the 2½-hour version made it to screens in 2011 in very limited release, few seeing it despite “ample” critical praise. A year later, Lonergan recut a longer version — three hours — available on DVD and for streaming.

The film’s legal struggle is a more interesting subject than its classroom debates. Producers are not the artists, but apparently, according to the details of the case, if you’re putting up the money, you have a say in what you get.

That is and should be troubling to those who cherish artistic freedom. But consider Gilbert’s point. “Margaret” receives 74% critical approval on Rotten Tomatoes, a decent number, but is actually deemed a bust by a majority of the audience. Those numbers are at odds with a “Margaret” character’s observation that people decide they like a performance only after reading that a critic likes it. Clearly Lonergan set out to make a more artistic and less mass-markety film than Gilbert was bargaining for.

Regardless of fault, the delay matters. A film languishing 5 or 6 years, and finished at least twice, is clearly flawed. It still could be a masterpiece. At least one notable critic thinks so, because it’s a movie about “behavior,” though he concedes it “rapidly unravels in the last third.”

Not content with a street tale such as “Maria, Full of Grace” — which Paquin’s Lisa is entirely capable of providing — “Margaret” constantly tries to tell us how smart it is. Characters debate the opera. We hear about the Bard, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Israeli settlements. The film is concerned with three classrooms; one a geometry course in which everything is irrelevant except Mr. Aaron’s attention; another is a poetry class (with a handy list of 19th-century greats on the chalkboard) led by a frustrated teacher who can't get obviously well-versed students to interpret Shakespeare the same way he does — or interpret Shakespeare at all.

Then there is the two-teacher poli sci exercise that feels like a “Crossfire” episode on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. (If the Syrian student weren’t enrolled, chances are, the discussion would’ve been pretty one-sided.)

There is also a drama production in which the real performance is a series of backstage Dr. Phil moments.

It’s a high school, but these are prodigious, college-bound students. They battle with instructors not over truths but whether what they’re discussing is relevant and mock “scholarly opinion.” Intentional or not, “Margaret” portrays higher education at its most cynical if not most accurate. The goal isn’t to learn, but to demonstrate how smart one is, maybe so that employers and peers will notice, or maybe because it’s just what smart people do.

Lisa from the opening scene has already figured this out, putting her a step ahead of her peers and instructors.

Were Lisa non-white, attending a poor school, the plot might well be the same. Blowing off studies, experimenting with sex, witnessing an accident, dealing with police, clashing with mom. To his credit, Lonergan has crafted a universal story that happens to be in an upscale environment, much like “Ordinary People” illustrated how the wealthy aren’t perfect.

The source of Lisa’s problems is not her disdain for schoolwork. It’s boredom. Once in a while (think “The Bling Ring”), a movie excels at depicting this underrated scourge of the First World. When people do not have to struggle for food or shelter, they need other endeavors to pass the time. One unfortunate option is crime. Lisa won’t sink that far; she prefers casual sex, maybe some drugs, or a police department escapade, shopping for proper Southwest clothing.

But the boredom has led to another problem. Guilt. On two levels. One of her frivolous moments led to a fatal accident. She contributed to its cause and covered up the truth. It was not the Crime of the Century. But an innocent person has died, and Lisa shared the woman’s final moments.

“Margaret” impressively shows that people’s initial reaction to a bad event is not grief, but shock, and “how do I stay out of trouble.” Only later, according to the movie, is when the trauma of the event accumulates. Most, even teens, at that point would consult a shrink. Lisa has another idea — playing offense. She attempts a redo, demanding police or the legal system punish not her but an offender she initially protected. This is no halfhearted fancy. She visits the offender at his home and calls on the police investigator, Mitchell, multiple times.

Why Mitchell doesn’t ask to meet with a parent in this serious situation, who knows, and why there are somehow no other witnesses on a congested New York City intersection defies belief. But this is a world in which teenagers are the superior species. Students overwhelm their elite instructors. Lisa talks to her mother, Joan (herself ripe for character analysis), as though they were sisters, with heightened profanity. Lonergan clearly likes the contrast of Joan’s childlike fragility with Lisa’s no-holds-barred assertiveness. There’s quality drama here, if it’s utterly impossible to believe that Lisa and her mother are related in the slightest.

Often, movies about characters who are actors (let’s see, same town, how about “The Goodbye Girl”) leave you wondering whether the characters actually are good actors. Lonergan assures you Joan’s a legit star with J. Smith-Cameron’s spectacular impersonation of Shirley Temple.

Lonergan unfortunately paints Lisa in a box. We admire her for her honesty. That is what should carry her through growing pains. But in her most important statement, she lies. Why? He gives us no convincing explanation or motivation. The rationale is sympathy; she senses trouble for the driver, a complete stranger, and immediately concludes his infraction did not merit the trouble he will receive. But Humanitarian Lisa is fleeting; she gradually counters a regret with an ambitious overreaction — she wants the driver fired and jailed and is angry that society can’t overcome her decision. None of that is admirable.

With strange depictions of clients interrupting reasonable lawyers, Lonergan stretches artistic license to the breaking point by forcing Lisa and Emily to beg for legal representation. A public transit vehicle killing a human being (provided not a suicide) is pure gold for a personal injury lawyer; no way would the women need to prod friends to look into taking the case.

It seems the movie could have stumbled into an accidental conclusion — that society has mechanisms for the consequences of behavior and that individuals should let those mechanisms work and not try to interfere. A fine observation. That type of viewpoint would have to show the driver as a future risk to the road. But this movie isn’t about unreliable transit operators.

New York City is a common backdrop for film. Lonergan loves his skyline shots. Many are beautiful. They, like slo-mo sidewalk scenes of crowds of people walking, are thrown in whenever the script needs a pause, as crutches to compensate for the inability to coat many of the apartment/classroom/law office scenes with vestiges of New York. In “Saturday Night Fever,” “Manhattan” and “Wall Street,” we always know where we’re at; in “Margaret,” we could just as easily be in Houston.

Lisa’s dad, Karl, played by Lonergan (he also gave himself a small but important role in “You Can Count on Me”), is not in New York City, but Southern California. This necessitates a common crutch, phone calls. The first is tedious; the follow-up attempts at milking the macguffin of an Arizona trip are agonizing.

Some movies deal with the confounding randomness of life. Why does this person get cancer; why did this person have a disabled child. Alison Janney’s Monica Patterson is a woman of extraordinary bad luck who represents futility. We learn far more about her in death than life; this is not the first movie with that approach. She had no close relatives and almost no close friends. Her life will ultimately be valued at $350,000 cash, a sum destined for pockets neither needing it nor expecting it. A case as perfectly pointless as perfectly legitimate.

The point of “Margaret” is not what Monica Patterson’s luck means to Monica Patterson, but what it means to Lisa Cohen.

“Margaret” unfortunately raises the specter of how often do inappropriate student-teacher relationships occur. It suggests maybe the most important attribute of a male high school teacher is ability to resist bodacious young women. It also suggests a relentless mutual attraction among both parties to do the wrong thing. This is evident in the opening scenes, Lisa demonstrating her frisky attire to Mr. Aaron, a serious-sounding instructor who gives her slightly more personal leeway than he should ... and then later he will give more ... and more ... and then way too much.

Was it any good for him? We can tell the answer is no, even before he condemns himself.

Lisa clarifies it for him. “It’s just sex. You’re acting like a little kid. I’ll see you in school.”

Despite that scolding, Lisa’s sexual agenda is limited. Is Mr. Aaron the end game, or the next stage after an uninteresting experience with a classmate. It’s more likely the former, for now, given that Lisa seems not interested in her grade and makes no such move toward lawyers or police who also could help her cause.

Where does Lisa plan to be in a year? There’s no mention of college preparation. Her parents are elites, so surely she’ll end up in an esteemed institution, maybe not to graduate but to check out the scene.

She is likely bound for a deputy position at a Bulge Bracket bank, a dual threat to Wall Street rivals, seducing clients (hopefully figuratively) when not elbowing aside the primarily-opposite-gender Masters of the Universe.

Who is “Margaret,” anyway? This is Lisa’s film, probably not a masterpiece, but Paquin’s piece de resistance.

3 stars

(September 2016)

“Margaret” (2011)

Starring Anna Paquin as Lisa Cohen ♦

J. Smith-Cameron as Joan ♦

Mark Ruffalo as Maretti ♦

Jeannie Berlin as Emily ♦

Jean Reno as Ramon ♦

Sarah Steele as Becky ♦

John Gallagher Jr. as Darren ♦

Cyrus Hernstadt as Curtis ♦

Allison Janney as Monica Patterson ♦

Kieran Culkin as Paul ♦

Matt Damon as Mr. Aaron ♦

Stephen Adly Guirgis as Mitchell ♦

Betsy Aidem as Abigail ♦

Adam Rose as Anthony ♦

Nick Grodin as Matthew ♦

Jonathan Hadary as Deutsch ♦

Josh Hamilton as Victor ♦

Rosemarie DeWitt as Mrs. Maretti ♦

Glenn Fleshler as 1st Man ♦

Stephen Conrad Moore as 2nd Man ♦

Gio Perez as Kid ♦

Matthew Broderick as John ♦

Jake O’Connor as David ♦

David Mazzucchi as Lionel ♦

Jerry Matz as Mr. Klein ♦

Kevin Carroll as Mr. Lewis ♦

Hina Abdullah as Angie ♦

Olivia Thirlby as Monica ♦

Kenneth Lonergan as Karl ♦

Enid Graham as Bonnie ♦

Brittany Underwood as Leslie ♦

T. Scott Cunningham as Gary ♦

Michael Ealy as Dave The Lawyer ♦

Renee Fleming as Opera Singer ♦

Susan Graham as Opera Singer 2 ♦

Adam Lefevre as Rob ♦

Krysten Ritter as Salesgirl ♦

Matthew Bush as Kurt ♦

Anna Berger as Neighborhood Lady #1 ♦

Rose Arrick as Neighborhood Lady #2 ♦

Pippen Parker as Opera Fan ♦

Stephanie Cannon as Woman Mourner #1 ♦

Kevin Geer as AIG Detective #2 ♦

Kelly Wolf as Annette ♦

Johann Carlo as Neighbor ♦

Carlo Alban as Rodrigo ♦

Christine Goerke as Opera Singer “Norma” ♦

Liza Colon-Zayas as Nurse ♦

Jason Pendergraft as Young Cop (Not Photographed) ♦

Yves Abel as “Hoffman” Conductor

Directed by: Kenneth Lonergan

Written by: Kenneth Lonergan

Co-producer: Blair Breard

Executive producer: Anthony Minghella

Producer: Sydney Pollack

Producer: Gary Gilbert

Producer: Scott Rudin

Original music: Nico Muhly

Cinematography: Ryszard Lenczewski

Editing: Anne McCabe, Michael Fay

Casting: Douglas Aibel

Production designer: Dan Leigh

Stunt coordinator: Manny Siverio

Stunts: Don Hewitt, Cort Hesslor, Niabi Caldwell, Jeff Ward, Brianna L. Farfel, John McLaughlin, Roy Farfel, Michael Burke, Damian Achilles

Unit production manager: Blair Breard, Jennifer Roth

Production supervisor: David Bausch

Art director: James Donahue

Set decorator: Ron von Blomberg

Costume designer: Melissa Toth

Makeup and hair: Felice Diamond, Anita Gibson, Peg Schierholz, Thom Gonzales, Rob Van Dorssen, Tom Watson, Cookie Jordan, Roxanne Rizzo, Anthony Gueli, Ryan Sherratt

Post-production supervisor: Alexis Wiscomb

Very special thanks: The Metropolitan Opera