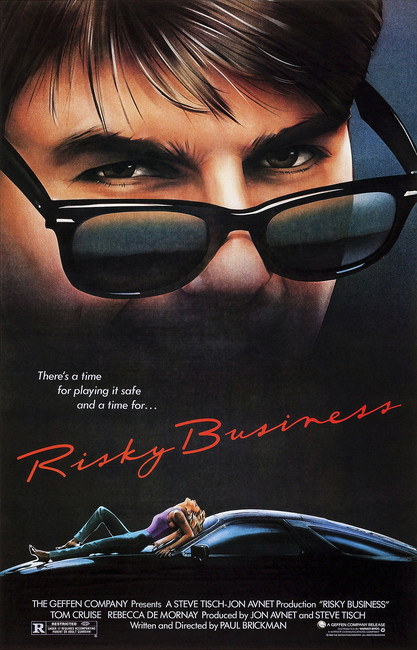

A star was born: ‘Risky Business’ belongs to Tom Cruise; everyone else is just along for the ride

Prostitution fascinated the great international auteurs. Godard, Fellini, Bergman, Buñuel, Mizoguchi all explored it. Jean Eustache, not quite as well known, drew an extraordinary contrast of man’s dueling desires in 1973’s “La maman et la putain.” The most famous American film about prostitution is likely “Pretty Woman,” which delves deeply into ... corporate takeovers.

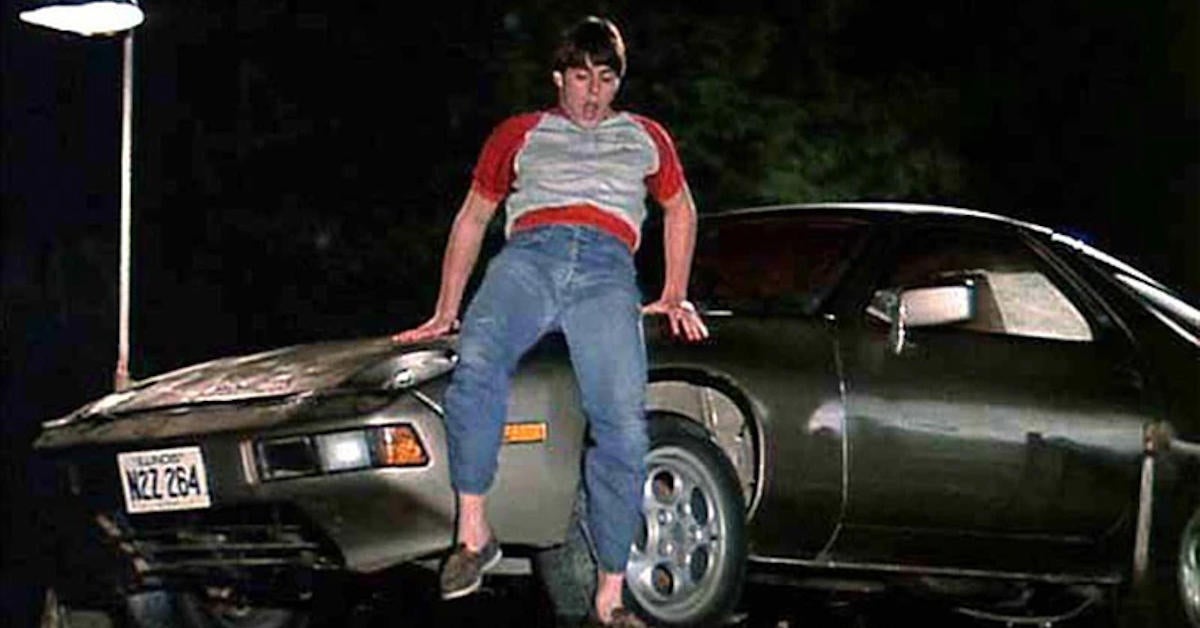

Most people could not name the director of “Risky Business,” a landmark 1983 teen hit not for how it deals with important social issues but because of how it depicts Tom Cruise in underwear. “Obviously I didn’t know it would have the shelf life it seemed to have,” Paul Brickman said 30 years later. That shelf life is still rippling through pop culture after four decades. A news exec at a PBS station in 2021 lost his job by demonstrating the scene in an Instagram post. There is a lot more to “Risky Business” than lip-synching with Bob Seger. Does that lack of acknowledgment bother Brickman? No, it’s the David Geffen-engineered U-turn of Brickman’s original stark conclusion that made the director feel like “the whole film was compromised by this cheesy happy ending.” If that makes you feel, as a viewer, that you’re being manipulated, welcome to Hollywood.

Sometimes critics are right for the wrong reasons. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert each ranked “Risky Business” the 9th-best movie of 1983. Siskel claimed with a straight face on their TV show that the movie “casts a jaundiced eye toward the great distance between the classes in the United States.” Ebert in a 4-star print review claimed “The very best thing about the movie is its dialogue.” He took 455 words before mentioning “Tom Cruise.”

Yes, Tom Cruise was already — on some level — famous. But not like this. Ebert’s review is the equivalent of someone writing in late 1914 that this George Herman Ruth might be a pretty good ballplayer. If Cruise was one of those people knocking on the door of Hollywood stardom, “Risky Business” bashed it in.

From the moment Cruise dances and flops to “Old Time Rock and Roll” — which occurs around the 10-minute mark — nothing else matters in “Risky Business.” That’s called lightning in a bottle. For whatever reason, the scene caught on, for the same inexplicable reason as an elderly woman saying “Where’s the beef?” When people mention “Risky Business” now, no one debates whether the ending is satisfactory or whether Brickman’s strange fascination with trains makes any sense. The scene was Brickman’s idea and the music was his idea too, though Cruise said he was offered the opportunity to choose something different and declined. The genius of casting Cruise? Apparently that goes to Nancy Koppler, or whoever decided that Cruise, and not Sean Penn or Kevin Bacon or John Cusack, best fit the bill.

(While everyone recognizes the song, probably few recognize the stereo equipment. Joel is playing what appears to be a Phase Linear 7000 series cassette deck. If you're looking for one on eBay, good luck. The equalizer, with the “preponderance of bass” that alarmed Dad, looks much like a Realistic 31-2000, which is much more available (and cheaper). There is more equipment in the cabinet that’s not quite visible, and it may or may not be the same equipment that Guido “sells” to Joel at the end of the movie.)

Joel Goodson is an underachiever. Tom Cruise is an overachiever. He realizes that Brickman’s script is not calling for method acting. To try to delve into the absurdity of why, at the beginning of the film, Joel can’t get a date, or why he even wants to go to Princeton given his lack of high scores and interest in classwork, isn’t worth the trouble. Cruise plays Joel like Cary Grant’s Roger Thornhill in “North by Northwest,” a humble everyman beholden to his mother, then enveloped by chaos around him and proving better at this line of work than the professionals he’s competing with. Cruise knows he just needs to say “Please leave” a bunch of times like a scared teenager, then put on the Ray Bans and flash the smile. (The official name of Cruise’s character is simply “Joel.” His last name is mentioned throughout the film, and most references spell it “Goodson,” but your closed captions may call it “Goodsen.”)

Cruise in “Risky Business” is like another Tom, Brady, in Super Bowl XXXVI. If you don’t know that one by Roman numeral, it’s Brady’s first, when he was considered a limited game manager just along for the ride, long before anyone called him the greatest of all time. Nobody knew it then, but this somewhat hesitant player was just beginning to show us how it’s done. Cruise is almost certainly the greatest screen performer of the last couple generations. Decades later, notice in “Risky Business” how many scenes are actually flat, tentative, like Brady on a limited playbook. Within a few years, Cruise could rattle it off in any genre, “Top Gun,” “Rain Man,” “Magnolia,” “Born on the Fourth of July,” “A Few Good Men.” (It wouldn’t hurt if someone told him his talents would be better served in something besides the fifth or sixth installment of “Mission: Impossible.”) Does the public even come close to appreciating him? He’s a little outspoken, sensitive to media intrusions, a polarizing religious figure, maybe at times a bit chippy. Well, not everyone likes Tom Brady, either.

Nearly all high school coming-of-age stories that actually get made into movies can be called “dramedies.” Are some completely serious? Sure. Name a few. (Not “Ordinary People.” Not gonna allow it.) The golden rule is that there has to be comedy. “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” “Grease,” “American Graffiti.” Like those selections, Brickman opts for absentee parents and, like at least three of those pictures, gives Joel no complaints about his upbringing. No ax to grind. The story, or at least the setting, has to be drawn from the writer/director’s own hometown, of course. (Imagine if a director had the gall to make a coming-of-age movie about someone else’s childhood.) Brickman, the son of syndicated cartoonist Morrie Brickman and wife Shirley, told Siskel in September 1983 that his parents saw the movie at least twice. “I think I understood what he was getting at,” Brickman’s mother told Siskel.

“Risky Business” isn’t edgy enough to be called a black comedy, but it’s on the path. Brickman said in 2001 that “No one knew what kind of tone I was working toward” and that “No one thought it was funny enough.” He told Siskel in 1983 he wanted a “mixture of tones.” The studios all rejected it, leaving it in the hands of Geffen, who was just launching his film arm. Under his orders, the Lana character went from 16 to 21. Hiring a lead actress still wasn’t easy. Michelle Pfeiffer wasn’t gung-ho about playing a call girl who seduces a high school boy. Rebecca De Mornay, at that point undiscovered, was willing. It’s maybe not just the character’s occupation that matters. De Mornay appears in a sideways nude scene, albeit from a distance with dress lifted up, but there is a brief glimpse of full frontal nudity, which may have scared the likes of Pfeiffer and others.

Brickman attempts some serious art-house effects in his opening scenes before resorting to convention. He starts with a tracking shot of downtown Chicago on a foggy night from a train, a scene which appears to have nothing to do with the rest of the film. The most curious camerawork shows Joel taking his parents to the airport from a first person point of view, only to have the camera swing around and show Joel as his parents depart. We have a noir-like flashing neon sign in Joel’s bedroom window. The introductory sequence tells us how the movie will go, but clumsily — it implies Joel is fantasizing about a neighbor who presumably doesn’t exist. Joel envisions the young woman in a steamy shower, then dreams he has forgotten about a class and an important exam and arrives three hours late and is sure to fail, a common dream virtually everyone has probably had and a nice touch here. Do these inspired pieces fit with a transvestite, a car in a lake, a pimp named Guido? No, “Risky Business” is kind of throwing stuff at the wall.

Ebert is right that there are a few great lines, but not nearly enough of them. “Who’s the U-boat commander?” “Some of the girls are wearing my mother’s clothing. I just don’t wanna spend the rest of my life in analysis.” And a hilarious interruption locals will appreciate: “This is my cousin Ruben, he’s from Skokie. ... He’s gotta be back by 12 o’clock.”

On the Tom Cruise Personality Meter, “Risky Business” comes down on the side of “A Few Good Men,” not “Top Gun.” Joel Goodson, like Daniel Kaffee, is underachieving because he’s too conservative, he needs to relax, let it all hang out, just declare “What the f---,” then success will happen for him.

That may well be what actually happens on Chicago’s North Shore (specifically, Brickman’s old stomping grounds of Highland Park, as well as the Bahá’í temple in Wilmette, included for no particular reason except apparently to excite Chicago moviegoers). Is there a theme of white privilege in “Risky Business,” that these suburban kids can have as much illegal fun as they want and still get rewarded for it? Yes, except De Mornay and her call girls and her pimp are all white, too. None of these kids is hardly ever shown studying, none of them ever gets busted for drinking, drug use or vandalism, and we know that even the ones who can’t get into Princeton are going to be driving Porsches around the North Shore, inviting the Lanas of the world into their orbits whenever bored. Brickman spent little to nothing on police cars. He does seem to agree with “Ordinary People” that North Shore moms can be more concerned about household valuables than their own sons.

Brickman’s shooting locations nicely feature his hometown, usually at night, but the cameras fail to draw any kind of meaningful contrast between the tony suburbs and city of Chicago. Whereas beautiful bridge visuals illustrate the gap that Tony Manero must cross from Bay Ridge to Manhattan in “Saturday Night Fever,” Joel’s only dilemma in “Risky Business” is whether to take the Porsche or the train. The Goodson family home could easily be a Hollywood lot trick — in other words, film some north suburban scenes on location but do all the house scenes, where the bulk of the film takes place, at a studio. Evidently, a real Highland Park home was used. Brickman’s most prominent Chicago scene is filmed not in an alley, where Lana may be desperate for a few dollars, but at the eminent Drake Hotel, whose management may or may not have been aware of the subject matter of the film.

“Risky Business” was not only a breakthrough for Cruise but for De Mornay. In her fairly prolific career, “Risky Business” proved the high-water mark. Was she a permanent victim of type-casting? It must’ve occurred to her during filming that “this woman was probably beaten, battered and abused somewhere before she became this North Shore kid’s plaything,” but she doesn’t let on. Cruise and De Mornay have a decent rapport but not an exceptional one, not like the way Cruise and Demi Moore would trade zingers a decade later in “A Few Good Men.”

De Mornay’s shortcoming here is that, unlike in “Pretty Woman,” the audience never cares if she and Joel become a couple, and so the drama is never more than circular, how to get her to go home/how to find her. Brickman’s efforts to develop a little emotion actually work against the movie — it’s more exciting to think of Joel having this girl as nothing more than on-call. Among its weaknesses, “Risky Business” will at times prompt Joel to ask Lana if their relationship is meaningful to her. Brickman told Siskel that his own ending had Lana and Joel sharing a powerful moment at the John Hancock Building’s 95th-floor restaurant, a closure that feels tedious. Coincidentally, “Risky Business” parallels a much different film, “The Electric Horseman,” in that its two leads are perfect business and romantic partners for a week who know they can’t be a couple any longer than that. That was evidently the conclusion Brickman was trying to make that Geffen didn’t quite appreciate.

“Risky Business” inadvertently seems to deliver a great truth — that while people may already be interested in illicit types of activities, they get really interested when those activities are supplied by trusty friends rather than underworld strangers. That’s an important problem in “Save the Tiger,” when Jack Lemmon must provide a favorite, and overbooked, call girl to Lemmon’s most important client or risk losing his biggest account. Joel Goodson’s friends of course wouldn’t be dialing up prostitutes to come to their own homes, but if they just need to bring a couple hundred dollars to Joel’s place, no problem. A Princeton “interviewer” (and who knew they made evening house calls to kids with mediocre grades?) doesn’t have to lie to his wife about spending the evening at Joel Goodson’s house. And who knew Princeton folks made evening house calls to kids with mediocre grades? It seems Joel’s dad is so wealthy or connected, it’d be good for Princeton to find a reason to let Joel in.

But just like in “Pretty Woman,” the girls of “Risky Business” are too good to be true. There’s not a whiff of trafficking and no party-crashing and virtually no drugs in this film, aside from an obligatory, token scene of Joel getting high and one obscure person at a party doing the same. There must be irony in the title here. “Risky” business? Joel’s dad can detect the tiniest of changes to the equalizer but not realize his house had been ransacked. Prostitutes and pimps take over the home, and neither the police nor neighbors nor high school nor Princeton care. Brickman probably got the ending he deserved.

3 stars

(October 2021)

“Risky Business” (1983)

Starring

Tom Cruise

as Joel ♦

Rebecca De Mornay

as Lana ♦

Joe Pantoliano

as Guido ♦

Richard Masur

as Rutherford ♦

Bronson Pinchot

as Barry ♦

Curtis Armstrong

as Miles Dalby ♦

Nicholas Pryor

as Joel’s Father ♦

Janet Carroll

as Joel’s Mother ♦

Shera Danese

as Vicki ♦

Raphael Sbarge

as Glenn ♦

Bruce A. Young

as Jackie ♦

Kevin C. Anderson

as Chuck ♦

Sarah Partridge

as Kessler ♦

Nathan Davis

as Business Teacher ♦

Scott Harlan

as Stan Licata ♦

Sheila Keenan

as Nurse Bolik ♦

Lucy Harrington

as Glenn’s Girlfriend ♦

Jerry Tullos

as Derelict on Train ♦

Jerome Landfield

as Kessler’s Father ♦

Ron Dean

as Detective with Bullhorn ♦

Bruno Aclin

as Mechanic ♦

Robert Kurcz

as Service Manager ♦

Jonathan Chapin

as Kid at Gas Station ♦

Jimmy Baron

as Kid at Window ♦

Harry Teinowitz

as Kid at Party ♦

Francine Locke

as Shower Girl ♦

Ann Cole

as Call Girl ♦

Candace Collins

as Call Girl ♦

Elizabeth Curran

as Call Girl ♦

Jill De Vries

as Call Girl ♦

Debra Dulman

as Call Girl ♦

Joyce Hazard

as Call Girl ♦

Kerry Hill

as Call Girl ♦

Megan Mullally

as Call Girl ♦

Lora Staley

as Call Girl ♦

Vivian Victor

as Call Girl ♦

Fern Persons

as Lab Teacher ♦

Cynthia Baker

as Test Teacher ♦

Wayne C. Kneeland

as Russell Bitterman ♦

Jade Gold

as Evonne Williams ♦

Dana Balkin

as Girl in Nurse’s Office ♦

Karen Grossman

as Hall Marshall ♦

Brett Baer

as Howie Rifkin ♦

Vinny Argiro

as Mr. Rents Salesman ♦

Eric Minsk

as Wimpy Kid ♦

Michael Genovese

as Rent-All Man ♦

Steven Charous

as Softball Player

Directed by: Paul Brickman

Written by: Paul Brickman

Producer: Jon Avnet

Producer: Steve Tisch

Associate producer: James O’Fallon

Music: Tangerine Dream

Cinematography: Bruce Surtees, Reynaldo Villalobos

Editing: Richard Chew

Casting: Nancy Klopper

Production design: William J. Cassidy

Set decoration: Ralph Hall

Costumes: Robert de Mora

Makeup and hair: Ilona Bobak, Lillian Toth

Unit production manager: John G. Wilson

Post-production supervisor: Jeffrey Harstedt

Stunts: Rick LeFevour, Joe Shapiro, Steve M. Davison, Reid Rondell