‘Hard Eight’ is one person’s pinnacle; for another, the best is yet to come

The concept of Gentlemanly Conduct is as extinct in cinema as in everyday life. Watching it being played, straight, in a modern movie — and for these purposes, the 1990s counts as “modern” — takes a little getting used to.

Gangsters, though, are always in style, and eventually “Hard Eight,” the debut of director Paul Thomas Anderson, will get there. “Hard Eight” is a showcase for Anderson’s friend Philip Baker Hall, who may not have modeled his character, Sydney, on Marlon Brando’s Vito Corleone but checks all the boxes. The father figure who’s bolting the East Coast rackets for a new start in Nevada and wants the right way of life for his kids — who may be in some way adopted and who aren’t going to outrun pop’s calling.

Hall’s success here is in never dropping his guard, until late, either to the audience or the other characters. This is an emotionless life. Why is Sydney doing this again? is a question that will resonate. He might have a sinister plan, he might be on a guilt trip, he might’ve recently volunteered for the Salvation Army. As we anticipate signals, Anderson expertly conveys that whatever Sydney’s motivations, his lifestyle hasn’t changed. This is someone who’s been around the Nevada scene for a long time and is still at it. His calmness and comfort level in these surroundings suggest this is a person to respect. If not fear.

And what of that lifestyle. Do professional gamblers really exist? According to a 1997 New York Times article, “Only one-half of 1 percent of all gamblers fall into the professional category,” and experts estimated there are only 100,000 to 700,000 nationwide. Sydney’s career may be unlikely, but possible. That’s all Anderson needs.

We only see one sequence of strong evidence that Sydney knows what he’s doing, but it’s convincing. He explains to his newfound protégé, John, how the casino rate card and “comp” system works. This scheme is so blatant, it’s almost laughable, as though the floor can’t figure out what’s going on and is only granting John free accommodations because there aren’t many people there and the rooms are otherwise empty. But Sydney probably knows that. In a curious and slightly awkward crutch, the script will abruptly jump ahead two years, implying John has learned enough basics from Sydney to make a respectable living in Reno.

In noir, there are some comments that will be believed and many others that won’t. Notice that in “Hard Eight,” we rarely see Sydney gambling. And we can’t at all be sure about how much money he’s got or whether Sydney, or anyone else, is telling the truth about finances.

But we are treated to Sydney’s manners. Notice that not all of his courtesies, such as giving a woman her own motel room without expectation, are necessarily old-school. But his standards are from probably two generations previous, when people wore suits not just to casinos but everywhere, when people made a point not to use vulgarities in public, when people respected their elders. It is a treat to watch Sydney fight this losing, uphill battle. The criticism here for Anderson is that this battle is never really funny. Nor is it edgy. Does it have to be either? No, but in most movies, it helps.

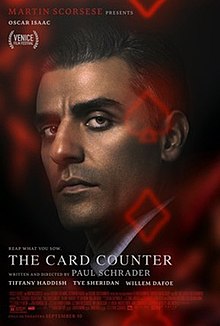

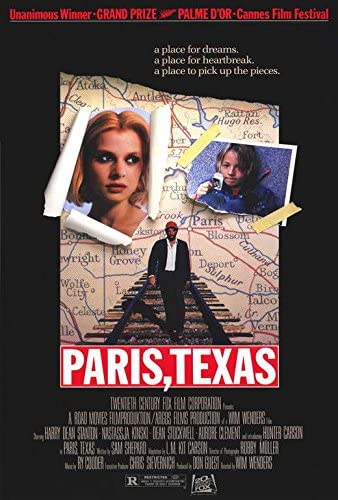

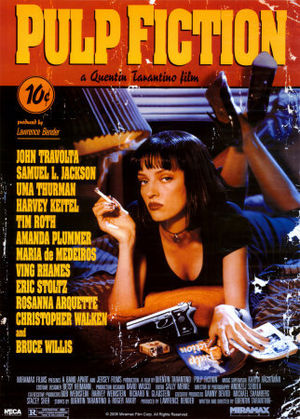

“Hard Eight” leans heavily on cinematic comfort food — diners and casinos. And motel rooms, but those are much more ambiguous locations where something bad often seems to happen. Diners are bonding places in “Pulp Fiction,” “Rain Man,” “Paris, Texas.” Who doesn’t like the idea of catching up with a friend over a plate of pancakes, or even just a cup of coffee. Casinos typically represent excitement, but not always, and not here. Consider Paul Schrader’s “The Card Counter” for a later example of the pleasantness — yes, that’s the right term — of visiting a mostly empty casino. Play a game, have a drink. However quiet, casinos are endless drama, and endless lights, a couple things no filmmaker can pass up.

This backdrop, and Anderson’s steady pace, makes “Hard Eight” repeatedly watchable. Rather than start with a mood, Anderson immediately makes us guess about why Sydney stopped to talk to this fellow. A backstory will emerge, but maybe there are other reasons. Sydney is lonely. He lives in hotels and eats at diners. Alone. His old friends must’ve passed on or simply retired. In his 1997 review, Roger Ebert says that about halfway through, there is “kind of a plot ... But the movie isn’t about a plot. It’s about these specific people in this place and time, and that’s why it's so good.” That plot, though, almost seems lifted from “Pulp Fiction,” where the old veteran is summoned to help careless crooks deal with a body. “Pulp” successfully plays it for laughs. “Hard Eight” disappointingly informs us that Sydney’s protégé and his associates are losers, no matter how much wisdom or security Sydney may impart.

But Anderson relies on that scene as the catalyst for the ending. Just as Quentin Tarantino would do a short while later in “Jackie Brown,” Anderson will put Samuel L. Jackson in a car with leverage over someone vulnerable. In “Jackie,” we already know what Jackson’s character is realizing; in “Hard Eight,” we are just beginning to learn the tantalizing backstory that is unfortunately all offscreen. Anderson could’ve kept his scene tighter. The outcome is an agreement under duress that feels as bogus as the extortion in “House of Sand and Fog.”

There must be a manual for how criminals set prices in the movies. A couple certain amounts, $6,000 and $2,000, surface and resurface in “Hard Eight.” Jimmy for whatever reason believes his silence is worth six grand. Is that a calculated assessment of the most Syd will or can pay, or an idiotic adrenaline rush? Jimmy doesn’t really need a gun for this type of extortion. Except, for some reason, he’s got to have the money NOW. Syd surely has necessary experience handling these kinds of situations in his life, but likely not recently. He nearly betrays to Jimmy how easy it will be for Syd to escape this one but catches himself, recognizing the biggest risk here is that Jimmy is not a real pro and may well get as careless or stupid as the John Travolta character does in “Pulp Fiction.”

In his review of “Taxi Driver,” Ebert famously described Jodie Foster’s character as a female who doesn’t want to be rescued. He could’ve said the same for Gywneth Paltrow’s Clementine in “Hard Eight.” That doesn’t stop Sydney from trying.

While “Hard Eight” is undeniably Hall’s movie, John C. Reilly, also an Anderson stalwart, plays dumb and never flinches. The stretch of John suddenly being successful in Reno two years after we meet him is on Anderson, not Reilly. Reilly and Hall are different acting styles than that of Paltrow, who oozes SoCal sorority but somehow emerged in not only this film but perhaps the grittiest commercial movie of the ’90s, “Se7en,” as the far-more-innocent wife of a cop. She has no chemistry with Reilly and may be viewed nowadays as less of an actress and more of a brand who got lucky hanging out with the right crowd. Bridging them all is Samuel L. Jackson, who clicks with everybody.

Though blessed with a remarkable cast, Anderson leaves out the type of character that Ebert calls the “reliable observer.” Jimmy comes closest, but he’s the villain. There is no one else watching this dynamic unfold between Sydney and John and John’s acquaintances, no one to connect a dot or vouch for someone. That sort of inclusion would threaten to put plot clamps on what we see, and as Ebert stated, it’s not about a plot.

Hard eight is the term for a pair of fours turning up in craps. According to the craps page in Wikipedia, a hard eight is also known as a “square pair” or even an “Ozzie and Harriet.” Craps is played in other films, such as George Burns’ “Going in Style,” perhaps a preferred game of filmmakers because of the occasionally raucous crowd behavior it inspires. Hard eight wagering is demonstrated in this film, but unlike blackjack, many people don’t know how to play craps, which saps some of the edge from the staredown between Sydney and the abrasive gambler played by Philip Seymour Hoffman. What are they trying to get, or not get, and who wins, not many may know.

The hard eight, we come to learn, is some kind of metaphor for Sydney’s life. Jimmy will mention once seeing Sydney bet $2,000 in Vegas on a hard eight. Evidently Sydney has done this often; he doesn’t remember that bet and has to ask Jimmy what happened. But Sydney clearly does remember a distinctive acquaintance whom Jimmy also noticed that night. Sydney’s abrupt ending of that conversation clevely informs us that Jimmy is aware of some details of Sydney’s past that Sydney wants no one, especially John, to know.

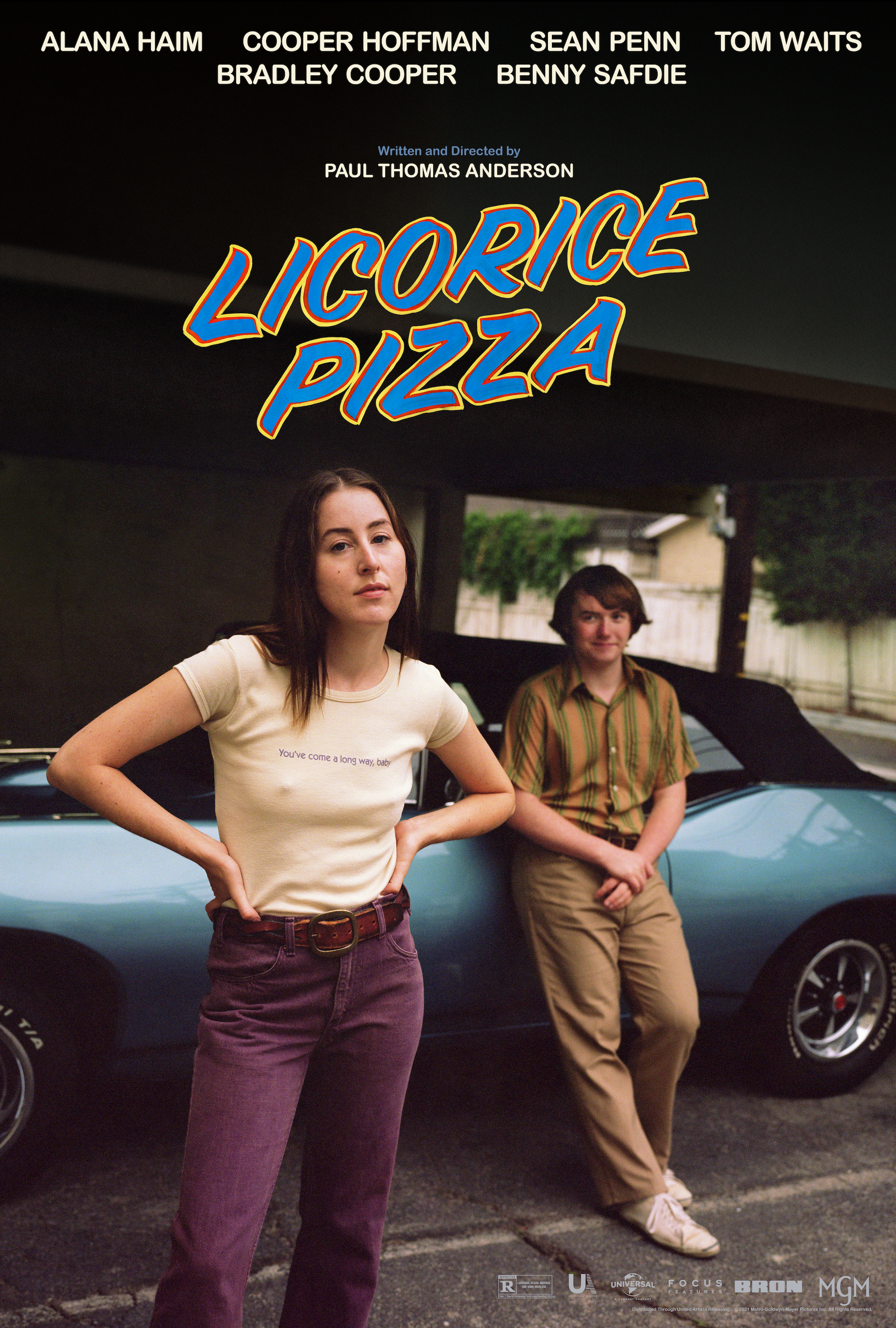

“Hard Eight” is significant for two reasons — it’s Anderson’s debut and Hall’s triumph. That’s no coincidence. They met on a PBS production, drank coffee and smoked together, and then Hall was floored by the “staggering” script Anderson had put together. Hall’s previous peak was the stage-to-film production of “Secret Honor,” in which his Nixon portrayal earned praise from none other than Pauline Kael. Are there any possible parallels between Sydney’s treatment of John and Hall’s friendship with Anderson? “Hard Eight” started out as a 20-minute short. Anderson was moderately successful, not completely successful, in converting it into a feature film. “Hard Eight” is in the headline of Hall’s obituary, but it won’t be in Anderson’s. He was only getting started.

One of the great underrated movie scenes is when Terence Stamp in “Wall Street,” after a losing negotiation with someone he despises, wishes everyone “Good night.” And he actually means it. Because he is a gentleman, and this is what gentlemen do. Sydney is trying to re-engage with a past life, the way things ought to have been, while making some sort of amends. Time has passed him by. There’s a little bit going forward, but there’s no going back.

3 stars

(May 2023)

“Hard Eight” (1996)

Starring

Philip Baker Hall

as Sydney

♦

John C. Reilly

as John

♦

Gwyneth Paltrow

as Clementine

♦

Samuel L. Jackson

as Jimmy

♦

F. William Parker

as Hostage

♦

Phillip Seymour Hoffman

as Young Craps Player

♦

Nathanael Cooper

as Restroom Attendant

♦

Wynn White

as Waitress

♦

Robert Ridgely

as Keno Bar Manager

♦

Kathleen Campbell

as Keno Girl

♦

Michael J. Rowe

as Pit Boss

♦

Peter D’Allesandro

as Bartender

♦

Steve Blane

as Stickman

♦

Xaleese

as Cocktail Waitress

♦

Melora Walters

as Jimmy’s Girl

♦

Jean Langer

as Cashier

♦

Andy Breen

as Groom

♦

Renee Breen

as Bride

♦

Jane W. Brimmer

as Aladdin Cashier

♦

Mark Finizza

as Desk Clerk

♦

Richard Gross

as Floorman

♦

Cliff Keeley

as Aladdin Change Booth Attendant

♦

Carrie McVey

as El Dorado Cashier

♦

Pastor Truman Robbins

as Pastor (voice)

♦

Ernie Anderson

as Pants on Fire Person

♦

Wendy Weidman

as Pants on Fire Person

♦

Jason 'Jake' Cross

as Pants on Fire Person

Directed by: Paul Thomas Anderson

Written by: Paul Thomas Anderson

Producer: Robert Jones

Producer: John Lyons

Co-producer: Daniel Lupi

Associate producer: Helene Mulholland

Executive producer: Hans Brockmann

Executive producer: François Duplat

Executive producer: Keith Samples

Music: Jon Brion, Michael Penn

Cinematography: Robert Elswit

Editing: Barbara Tulliver

Casting: Christine Sheaks

Production design: Nancy Deren

Art direction: Michael Krantz

Set decoration: David A. Koneff

Costumes: Mark Bridges

Makeup and hair: Lydia Milars, Alyson Murphy

Production manager: Craig Markey

Unit manager: Dan Collins

Stunts: Cliff Cudney, Bobby Andrew Burns