‘Promising Young Woman’ may be concealing an identity crisis

Geography is surely one of the many curiosities of “Promising Young Woman,” a revenge tale dubbed a “pitch-black dark comedy” by critic Richard Roeper. Most people come from Somewhere Else to attend med school and, upon collecting the degree, find Somewhere Else to live. Cassie attended med school apparently in the town she grew up in, and most people who attended med school with her apparently still live in this area, which must be swamped with physicians.

That’s artistic license, sure, or one of those nuisances that maybe doesn’t matter. Yet it seems odd for Cassie to be taking out her anger on random citizens rather than targeting her obvious foes until they just happen to drop in on her life and give her no choice.

Psychological trauma is an occasional and powerful movie concept that, cinematically, does not require effective or even accurate therapy to heal. Will Hunting’s problem is beating up people; once he admits he’s an orphan, he stops doing that. Tom Wingo needs to tell Dr. Lowenstein about a home invasion so his sister can be cured. Were “Promising” not a dark comedy, Cassie would be hitting rock bottom, sent to a therapist who violates some important standard of the client relationship, and handed her M.D. in cap and gown to smiles and hugs.

The great mystery in “Promising Young Woman” is whether Cassie and Nina are the same person. Start with the title. Does it refer to Cassie, or Nina? Nina is the mysterious macguffin. We never see her. Nor do we see the event that has so rattled Cassie. Nor are we ever told of what actually became of Nina, though suicide is implied. There is confusion in the early stages of the film as to whether Nina passed away during the incident in question. We hear comments about Nina that sound as though they easily could apply to Cassie. Top of her class, extremely bright, never the same afterward.

Female identity fluctuation is a theme of some of the greatest movies ever made. Bergman’s “Persona,” Hitchcock’s “Vertigo,” Antonioni’s “L’Avventura,” Altman’s “Three Women,” Lynch’s “Mulholland Drive,” Bunuel’s “That Obscure Object of Desire.” Emerald Fennell, a London-born actress making her directorial debut with “Promising,” leaves almost no daylight between Cassie and Nina other than one is with us, the other isn’t. All we know about Nina is whatever Cassie says about her, and the volume of what Cassie must say is a setback for this film, as is the impression that almost no one involved in the original crime/controversy seems to recall it without being given a synopsis.

If “Nina” did not really exist, there must be an explanation for multiple parents. Cassie’s are portrayed more as roommates, unable to reach their daughter emotionally and frustrated at her inability to lead a normal life. Are they part of the problem too? They seem oblivious to Cassie’s lingering trauma, and neither suggests therapy. Nina’s mother is more blunt, suggesting Cassie needs to move on. Is Fennell telling us it can’t be done?

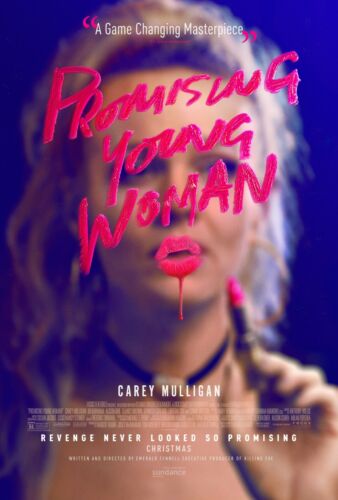

“Promising” is far more a character than a story. Fennell realizes what she’s got — a mesmerizing 360 from Carey Mulligan, who was once touted as the next Audrey Hepburn and owns the camera like few others. She loves the fashion show she’s handed here. Cassie is not particularly funny, which is another setback for a dark comedy. But Fennell shows an extraordinary range of Mulligan poses: intense, fierce, come-hither, withdrawn, condescending, wink and a nod, aloof, striking, vulnerable. Fennell gives Mulligan many stunning close-ups that never seem to last long enough. Credit cinematographer Benjamin Kracun. These shots impressively carry the film despite its static locations of coffeeshop, bedrooms, dining room, doctor’s offices and sidewalks, and nightclubs that must be seconds away from last call. “Promising” also relies heavily on expert work from Angela Wells’ makeup department. There are hints here of “Joker” (or any related Batman movie) of a character marking up his or her face to adopt a noir persona, though there is no implication of mental illness on the part of Cassie. She is perhaps too self-assured, never questioning anything she is doing.

Less successful than the photography is the decision to use unnecessary chapter arrangements. They halt the momentum and raise questions as to why they’re there. They are meant to draw a parallel to Cassie’s own notebook of successful encounters (oddly old-school, a spiral bound notebook). But the notebook says little beyond that Cassie has been meticulously planning this type of activity and views it as some sort of mission.

One scene threatens to disrupt the narrative. Cassie stops her car in the middle of the street. An irritated male driver pulls up alongside and berates her. Cassie calmly grabs a tire iron from her front seat (as though she were anticipating this opportunity) and smashes the other vehicle’s taillights and windshield while the stunned driver sits and watches. This is a hint that Cassie may be explosively violent, someone not just out for revenge but one who lives for these kinds of opportunities.

“Promising Young Woman” sets itself apart in that in nearly all the movies about a sexual assault, it’s a man taking the revenge. And in the climactic moment of “Promising,” we can see Cassie’s plan is not a battle of testosterone, but a setup.

Blame the Victim could be the film’s greatest frustration, but there’s a stronger implication that the perpetrators and witnesses to these acts don’t actually detect a victim. They are, on the surface, upstanding members of the community and according to the script, appear to believe that such standing makes them impervious to wrongdoing. For a while, the movie lulls us into the notion that Cassie and Ryan really are meant for each other and that there can be a happy ending here. The revelation that upends this notion is not unexpected but nevertheless jarring and rather dispiriting. One of the key statements comes from Cassie’s boss, who asks Ryan out of the blue if he has killed any kids. Don’t say you weren’t warned about him.

Why does Cassie do what she does? It involves a lot of time and effort and risk. Many films featuring a character on such a mission will show numerous successes before a crucial mistake. “Promising,” of course, never shows the hours Cassie must spend sitting awkwardly in a nightclub and pretending to drink and waiting for someone vulnerable to notice. She might be doing it out of extreme remorse, an albatross of a guilt trip for being unable to help Nina. Or it might be that she tried it and liked it.

Cassie seems to enjoy punishing women even more than men. Fennell suggests that the wrongs implied in this movie that are committed by men are as much a result of biology and alcohol as aberrant behavior. For women, Fennell implies a conspiracy, an unwillingness to stand up for each other, apparently either out of fear of offending the male establishment or out of disbelief that what happened was a serious crime. Did Cassie’s female targets have any reason to doubt what was alleged by Nina? The awareness of a video (which, incredibly, Cassie doesn’t know about) suggests no.

Released in December 2020, “Promising Young Woman” is perhaps a bookend to an early 2020 film with #MeToo influences, “The Assistant.” Both movies are directed by women. “The Assistant,” which is no comedy, also involves a young woman bothered by the treatment of other women. She takes it up the proper channels, and her problem is that not everyone believes there is a victim in the matter. Like Cassie, she has to contemplate chucking this career. Both films convincingly show that if you are not the subject of the offender’s interest, you might never notice a problem.

Like “Promising Young Woman,” the 2015 movie “Room” depicts a young woman struggling to deal with the aftermath of trauma. There is an element of victim-blaming and not nearly the same kind of self-assuredness. “Promising” draws a few parallels to Quentin Tarantino’s “Kill Bill” tandem, but Cassie doesn’t use any swords or similar flourish.

Another Tarantino film, “Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood,” involves a different type of revenge than what Cassie is doing, one in which the gratification belongs to the audience, not the heroes. That film, like “Promising Young Woman,” inadvertently reminds us that we generally can’t do to offenders as bad as what they do to their victims, and that overcoming trauma is best performed on the therapist’s couch.

3 stars

(February 2021)

“Promising Young Woman” (2020)

Starring

Carey Mulligan

as Cassandra ♦

Bo Burnham

as Ryan ♦

Adam Brody

as Jerry ♦

Raymond Nicholson

as Jim ♦

Samuel Richardson

as Paul ♦

Timothy E. Goodwin

as Monty ♦

Clancy Brown

as Stanley ♦

Jennifer Coolidge

as Susan ♦

Laverne Cox

as Gail ♦

Alli Hart

as Ruby ♦

Loren Paul

as Jeff ♦

Scott Aschenbrenner

as Jeff's Friend ♦

Christopher Mintz-Plasse

as Neil ♦

Alison Brie

as Madison ♦

Gabriel Oliva

as Alfred ♦

Bryan Lillis

as Tony ♦

Francisca Estevez

as Amber ♦

Lorna Scott

as Jean ♦

Connie Britton

as Dean Walker ♦

Casey Adams

as George ♦

Vince Lozano

as Simon ♦

Molly Shannon

as Mrs. Fisher ♦

Max Greenfield

as Joe ♦

Christopher Lowell

as Al Monroe ♦

Mike Horton

as Chip ♦

Steve Monroe

as Lincoln ♦

Angela Zhou

as Todd ♦

Austin Talynn Carpenter

as Anastasia

Directed by: Emerald Fennell

Written by: Emerald Fennell

Producer: Margot Robbie

Producer: Emerald Fennell

Producer: Josey McNamara

Producer: Ben Browning

Producer: Ashley Fox

Producer: Tom Ackerley

Co-producer: Fiona Walsh Heinz

Executive producer: Carey Mulligan

Executive producer: Glen Basner

Executive producer: Alison Cohen

Executive producer: Milan Popelka

Music: Anthony Willis

Cinematography: Benjamin Kracun

Editing: Frédéric Thoraval

Casting: Lindsay Graham, Mary Vernieu

Production design: Michael Perry

Art direction: Liz Kloczkowski

Set decoration: Rae Deslich

Costumes: Nancy Steiner

Makeup and hair: Daniel Curet, Angela Wells, Bryson Conley, Brigitte Hennech, LeeAnn Brittenham

Unit production manager: Reena Magsarili

Post-production supervisor: Tim Pedegana

Stunts: Monette Moio, Casey Adams

Special thanks: Francisca Alegria, Steven Berger, Gregory McKnight, Clifford Murray, Rena Ronson, Ida Ziniti