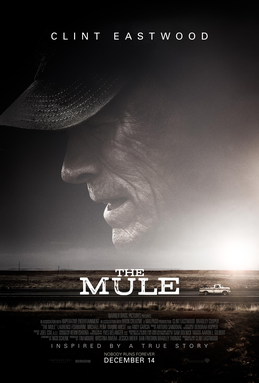

Clint Eastwood’s ‘The Mule’: If you put kilos in your car, it’s nobody’s fault but your own

Sondra Locke died on Nov. 3, 2018. Somehow, the passing of this Hollywood figure, known for her personal and professional partnership-turned-disaster with Clint Eastwood, wasn’t reported for weeks until Dec. 13, the night before the release of another one of his films.

Critics who all presumably wrote their reviews of Eastwood’s “The Mule” before Locke’s death became public can be forgiven for believing the film about a broken family might be semi-autobiographical and that “Eastwood himself might be concerned with these very issues.”

Maybe he is. Maybe he isn’t. Starting with 1992’s “Unforgiven” and perhaps earlier, Clint Eastwood achieved an auteur status that curiously prompted the same degree of critical pondering of his work shared by only one other director, Woody Allen. “What is the meaning of the film; is he really revealing something about himself?” It’s a bonus bestowed by a public that usually finds the people of Hollywood more interesting than their products.

One prominent critic who disliked “The Mule” (1.5 stars out of 4) nevertheless says the film is “rather touching” if “viewed as a Hollywood legend working through some personal issues about how he fared as a husband and father.” That’s quite a leap. It’s doubtful this critic or any others suggested that “The Godfather” could’ve been better if Brando had really been a gentleman of the Mafia who worried about bringing his youngest son into the fold.

So, reading into “The Mule” is a mistake. It has nothing relevant to do with Clint Eastwood’s life. It is a blow to the notion of victimhood. One prominent critic gets this totally wrong, stating Earl Stone is “victimized by the system.” The ride of “The Mule” is clumsy, papered-over and at least 15 minutes too long, but Eastwood delivers a point of view. Take it or leave it.

The film has drawn immediate comparisons to Eastwood’s moderate 2008 hit “Gran Torino,” but it has far more in common with TV’s “Breaking Bad.” Both “The Mule” and “Bad” depict a grown-up white male of some low-level stature motivated to do something alarmingly dangerous because, it seems, he really has nothing to lose. It should end badly in the first venture, but it doesn’t, because the newcomer is surprisingly well-suited and well-situated for this line of work.

Sometimes, his aptitude emerges unexpectedly. At times, he tells gun-wielding, 20-something gangster thugs what to do, and they are compelled to obey. That is entertaining drama. Carefully, since the days of “The Godfather,” the arts world has sketched out the boundaries for drug drama. If the characters 1) are not beating people up or robbing them of their money, and 2) if they give to the less fortunate, and 3) if they only fight in self-defense, and 4) if they ever served in the armed forces, then they are acceptable protagonists, even able to garner sympathy from the authorities chasing them.

This standard allows “The Mule” to come across as “comedy.” Perhaps some scenes are funnier than Eastwood and screenwriter Nick Schenk (who also wrote “Gran Torino”) expected, creating a witch’s brew of danger, laughs and redemption in the lengthy life of Earl Stone. Yes, it’s possible someone might get shot, but this is hardly “Scarface,” and we’re more likely to see the gringo driver asking about the supplier’s son and being thanked for doing so. But if we’re not laughing, we have to dig in with a halfhearted story of a character who doesn’t spend enough time with his family. (See, in “Dirty Harry,” Clint actually thought that the family lifestyle was only right for certain people.) Too many scenes feel like parts on order. Financial failure, a crutch in so many films that must be spoken because it’s so hard to show, is a major catalyst here. And it makes almost no sense. Earl is a gardener, not a newspaper publisher. The Internet should not be sinking his business. He should have ample funds for retirement. But for there to be a movie, he has to be introduced to the dark side at a vulnerable moment, and this happens in an unbelievably thin exchange. (If his granddaughter is friends with people like this, that’s definitely not a good sign, but the movie conveniently forgets that this might be an issue.) A certain number of confrontations must occur with females who recite for viewers Earl’s ledger of fatherhood and spousal failures for each generation. These scenes are instantly too long, but just when we need someone who has no reason to forgive to actually forgive and deliver us an ending, bingo.

Of course, Earl will have to get out of a few jams, and these scenes work, sometimes beautifully. What doesn’t work is the notion of Earl as a ladies man. Why is he alone in life? His compliments to older women are worthy of chuckles, but his bikini exploits in Mexico are so bad, they’re kinda funny. Eastwood clearly likes these images, and in a way, he’s right: Isn’t the poolside partying the best part about being in the drug business? Surely that’s more fun than target shooting. This is what Earl’s activity enables and why so many pursue it, even if that’s not his own murky rationale. (By the way, um, “The Mule” is a little bit over the top.)

Does Earl know what he’s doing? He’s too good at it for the answer to be “no.” The closing statements suggest an argument that the elderly, even without dementia, may not possess the best judgment. While not suggested in the movie, it does seem the elderly are disproportionately targeted by phone-call scammers. But diminished judgment is at odds not only with many scenes in “The Mule” but so many famous films, such as “The Godfather,” “Star Wars,” “The Paper Chase,” even “Chinatown.” One critic convincingly implies that Earl can’t really be a patsy and can’t really have dementia. Another reviewer seems to think Earl might not actually know what he is hauling until he takes a peek and expresses “shock.” That seems farfetched, given that upon accepting the job, Earl is greeted with guns and threats and very specific orders of a clandestine nature. If we believe Earl really is mixed up, we’ve got a movie that seriously does not work.

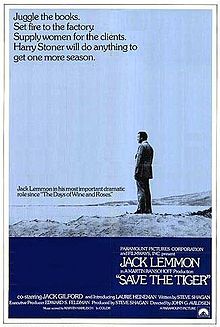

In fact, other than a curiosity, Earl’s age seems mostly irrelevant to this story. The real-life Earl, whose name was Leo Sharp, indeed drove drugs in his 80s (if you think wanding grandmas at airports is silly, this story will make you rethink that) and was profiled in 2014 by Sam Dolnick in The New York Times magazine (the fact the movie is inspired by the story but uses different names suggests a middle level of compensation for the source). But Eastwood’s film would be the same story whether Earl was 50 or was a laid-off accountant. There are some strains here of the real-life Bernie Madoff story and considerable parallels to 1973’s “Save the Tiger,” in which Jack Lemmon’s Harry Stoner has seen business dry up and resorts to illegality. The catch is that Harry is a war veteran who more than paid his dues but has been cursed by fate. When you’ve had to bury your band of brothers and seen youngsters grow up not appreciating it, flaunting the law to stay afloat is not a deal-breaker.

Its uninspired, obligatory scenes aside, “The Mule” could soar if it had the signature scene of “Gran Torino,” which shows Walt taking a bath, having reached the conclusion of what his life is worth. Earl’s demise is remarkably boring and tedious, as though the director realized as much and decided more sirens and police cars and even a helicopter would help.

A figure of Eastwood’s presence can get virtually anyone to do a film with him. Beefing up “The Mule” are Bradley Cooper, Laurence Fishburne, Dianne Wiest and Andy Garcia. Cooper, easily in his prime, acted the hell out of “A Star is Born” with Lady Gaga, but “The Mule” doesn’t take him or his story even remotely seriously enough for his stature; this role and those of the other supporting characters should’ve been given to up-and-comers who could use a break.

The beautiful presence here is Eastwood, easily on the short list of Greatest Film Actor. It might be Bogart, Brando, Gable, Grant, Nicholson or Pacino. Eastwood is more polarizing than all those others but incredibly resilient. Those who never cared for his Western or Dirty Harry motif can’t deny the prodigious list of exceptional thrillers that includes “Escape from Alcatraz,” “In the Line of Fire,” “Where Eagles Dare,” “Firefox,” “The Eiger Sanction,” and the powerful “The Bridges of Madison County.” Though far from his best work, “Every Which Way but Loose” and “Any Which Way You Can” (those are difficult titles to remember precisely) were massive box-office hits.

Easing through old age, Eastwood knows he thrives now as a curmudgeon who still has a flame in the belly. In “The Mule,” he is not just mirroring his portrayal of “Gran Torino” but Peter Fonda’s turn in “Ulee’s Gold.” All three movies depict an angular, lumbering veteran who has fought family issues for far longer than he fought communists, but during wartime, he realized something about himself, that he’s a little lucky. When each grudgingly takes a stand, he fills the screen, and the younger antagonists with their weapons seem no match. Eastwood is a skilled director but off the charts as a film actor, and it is actually disappointing that in this century, he has only 6 acting credits compared with 16 films directed. Now 88, may he not retire anytime soon.

“The Mule” cements notions of “Gran Torino” that, while the body declines, age gives us something important, a type of savvy and fearlessness. And a certain latitude. Critics have denounced perceived racist sentiments in “The Mule” though America laughed when Archie Bunker was saying it. There’s John Huston’s famous “Chinatown” line, “Of course, I’m respectable. I’m old.”

“The Mule” is not just what Earl Stone does, it’s what he is. He may be right. He may be wrong. He’s here to prove that whether fate smiles or frowns on us, our decisions are our own, and we should live with them. Earl’s victory is not in delivering drugs or visiting his ex-wife. It’s volunteering the judgment, “Guilty.” Earl does not carry a gun, but Eastwood blows away victimhood.

3 stars

(December 2018)

“The Mule” (2018)

Starring

Clint Eastwood

as Earl Stone

♦

Bradley Cooper

as Colin Bates

♦

Taissa Farmiga

as Ginny

♦

Michael Peña

as DEA Agent

♦

Alison Eastwood

as Iris

♦

Andy Garcia

as Laton

♦

Laurence Fishburne

as DEA Special Agent

♦

Dianne Wiest

as Mary

♦

Jill Flint

as Pam

♦

Clifton Collins Jr.

♦

Manny Montana

as Axl

♦

Robert LaSardo

as Emilio

♦

Katie Gill

as Sarah

♦

Noel Gugliemi

as Bald Rob

♦

Ignacio Serricchio

as Julio

♦

Loren Dean

as DEA Agent Brown

♦

Lobo Sebastian

♦

Diego Cataño

♦

Eugene Cordero

as Luis Rocha

♦

Daniel Moncada

as Eduardo

♦

Victor Rasuk

as Rico

♦

Devon Ogden

as Pretty Woman

♦

Lee Coc

as Assault Rifle Guy

♦

Monica Mathis

as Pedestrian

♦

Ashani Roberts

as Pretty Nurse

♦

Kaitlin Hodson

as Bridesmaid

♦

Derek Russo

as Big Dude

♦

Sparrow Nicole

as Ashlyn Bates

♦

Shaun McMillan

as DEA Agent

♦

James William Ballard

as State Trooper

♦

Casey Corley

as Bridesmaid

♦

Rey Hernandez

as Illinois State Trooper

♦

Cesar De León

as Jose

♦

Austin Freeman

as Mike

♦

Timothy Carr

as Prisoner

♦

Javier Vazquez Jr.

as Mexican-American Guy

♦

Michael H. Cole

as Banker

♦

Kenny Barr

as Swat Captain

♦

Joe Knezevich

as Dave

♦

Caroline Avery Granger

as Hot 45 Year Old Woman

♦

Tess Malis Kincaid

as Attorney

♦

Felicia Dee

as Biker 1

♦

Sandy Givelber

as Attorney

♦

Pete Burris

as DEA Regional Manager

♦

Almendra Fuentes

as Chola

♦

Mia Rio

as Chola Girlfriend

♦

Charles Lawlor

as Phil

♦

Dayna Beilenson

as Judge

♦

Keith Flippen

as MC

♦

Paul Alayo

as Sal

♦

Travina Springer

as Cute Wife

♦

Chris Goad

as Restaurant patron

♦

Grant Roberts

as DEA Agent

♦

Adam Drescher

as Daylily Computer Guy

♦

Cecil M. Henry

as DEA Agent

♦

Jay Gutierrez

as Cartel Enforcer

♦

Marco Schittone

as LJ Bates

♦

Saul Huezo

as Andres

♦

Jan Hartsell

as Beauty School Administrator

♦

Patti Schellhaas

as Driver

♦

Scott Dale

as The Clown

♦

James Tilley

as Chicano Gangster #1

♦

Jaylon Gordon

as Kid #2

♦

Rene Herrera

as Bodyguard to Laton

♦

Mallory Kidwell

as Bikini Girl

♦

Rashaan Matthews

as Prisoner

♦

Jim Kirsch

as Federal Agent

♦

Angel Luis

as Cartel Member #1

♦

Wes Weems

as Doctor

♦

Milton Saul

as U.S. Marshal

♦

Jeffrey S Smith

as Wedding Guest

♦

Jackie Prucha

as Helen

♦

Andrea Antonio Canal

as DEA Special Agent

♦

Patrick L. Reyes

as Mexican Farm hand #3

♦

Jessica B. Wellington

as Biker #2

♦

Becky Altringer

as Driver

♦

Billy Richards

as Helicopter Pilot

♦

Gustavo Muñoz

as Farmhand

♦

Christi McClintock

as Day Lily Fan

♦

Donovan Elmore

as Kid#1

♦

Megan Mieduch

as 24 Hour Waitress

♦

Alexandra Erickson

as Cheerleader

♦

Leonard Hennessy

as Pastor

♦

Ester Menendez

as Chola

Directed by: Clint Eastwood

Written by: Nick Schenk

Inspired by: New York Times Magazine article by Sam Dolnick

Producer: Clint Eastwood

Producer: Dan Friedkin

Producer: Tim Moore

Producer: Bradley Thomas

Producer: Jessica Meier

Producer: Kristina Rivera

Co-producer: Jillian Apfelbaum

Executive producer: Aaron L. Gilbert

Executive producer: David Bernad

Executive producer: Ruben Fleischer

Executive producer: Todd Hoffman

Music: Arturo Sandoval

Cinematography: Yves Bélanger

Editing: Joel Cox

Casting: Tara Feldstein, Chase Paris, Geoffrey Miclat

Production design: Kevin Ishioka

Art direction: Rory Bruen, Julien Pougnier

Set decoration: Ronald R. Reiss

Costumes: Deborah Hopper

Makeup and hair: Patricia DeHaney, Jay Wejebe, Lori McCoy-Bell, Chawana Jones, Devin Shayla Morales, Jennifer Nieman, Mollie Siegel, Jordan Venetis, Heather Beauvais

Executive in charge of production: Mark Scoon

Stunts: Doug Coleman, Allen Robinson, Paul Chappell, Dean Grimes, Bobby Hernandez, Derek Russo, David Alessi, Jenny Jerman, Warren Jones, Trent Brya, Eliza Coleman, Scott Dale, Alexander Hashioka Oatfield, C.C. Ice, Aaron Matthews