Warren Beatty and Julie Christie are an early ’80s match made in ‘Heaven Can Wait’

Pauline Kael championed classic screwball comedies. Curious, then, that she wasn’t terribly impressed by Warren Beatty’s football romance “Heaven Can Wait,” calling it a “little smudge of a movie.”

“It wasn’t bad,” Kael admits in a September 1978 assessment of the summer’s box office winners, of which this film was one. But she openly wonders, “Why, then, does it offend me when I think about it?”

Whoa. Another accomplishment for Beatty, this one not widely noted: He has made a film so good and so experimental, it offends the toughest critics.

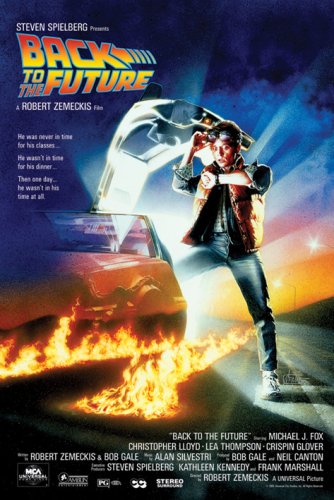

You heard that right. “Experimental.” The best movie Warren Beatty ever made. No, not “Bonnie and Clyde.” That was a great movie, albeit rightly controversial, for other, more straightforward reasons. “Heaven Can Wait,” a rom-com remake of a film released three decades earlier (actually, “remake” is slightly debatable), is somehow one of the pioneers of that “Back to the Future” tree, splendid entertainment that makes us wonder about time and space and destiny, afterlife and God.

“What makes you feel good about the movie is that it says you’re not going to die,” Beatty explained to Frank Rich for his Time magazine “Mr. Hollywood” cover story in 1978. Interesting, because several more serious films have quietly made the same implication. Death, the strongest human drama, is generally the most powerful cinematic drama. A movie that takes death off the table is a curiosity.

Well, wait a second — “Heaven Can Wait” doesn’t exactly nix the concept of dying. It tells us we keep going, but separate from the world we know, like a team eliminated from the NCAA basketball tournament. “Heaven” joins other movies of this curious genre in allowing limited earthly interaction, although “Heaven” declares that the interaction is only because of a technicality. Beyond that, it throws up its hands and freely admits, “Have no clue.”

Neither Kael nor Roger Ebert nor Gene Siskel mention the crucial decision made by the “Heaven Can Wait” filmmakers: That when Beatty’s character inhabits two other bodies, viewers will see Warren Beatty (the soul), while the other characters will be seeing some other person.

That is a potentially huge misfire. Other movies such as “Freaky Friday” have done the out-of-body switch, but generally, the audience and the other characters are seeing the same faces. In “Heaven,” we’re not. When Joe-as-Leo is trying to convince his coach Max Corkle that Leo really is Joe, it’s totally obvious to the audience, but the Jack Warden character is seeing something totally different. Julie Christie’s Betty Logan is being admired by two totally different men who look nothing like Warren Beatty. Those are risks, even for screwball comedy. Once the filming starts, it’s a done deal. If rethought, there would be too many scenes to reshoot.

What are the other ways this concept could’ve been done? A lesser-known actor could play average-looking Joe Pendleton, and once Joe inhabits the body of Leo Farnsworth, we would see Warren Beatty as Leo talking and acting like the Joe actor, and Joe the character would be intrigued by suddenly finding himself no longer a quarterback but a handsome business mogul. That is probably doable, except the original Joe character — in gray sweatsuit — appears effectively throughout the movie, and Beatty would be the supporting character, and audience loyalties (particularly over the romance) would be divided.

So the best bet is showing Warren Beatty all the time. Make the script do it. Indeed, that’s probably why Kael scoffs that Beatty isn’t really acting here or pushing himself, it’s just “image-conscious celebrity moviemaking.”

Conscious of image, and a whole lot more. It’s nearly impossible to reign over a picture as much as Beatty in “Heaven Can Wait.” He’s the producer, the director, the writer, star, the publicist. And while a few of those distinctions technically have “co-” in front of them, those are legit descriptions for Beatty, this is hardly outsourcing. When it doesn’t work, it’s a massive overreach. When it works? Give the credit where credit is due. Beatty not only delivered a big hit, he picked up four Oscar nominations of his own. Nine other people in the production received Oscar nominations. This is a screwball comedy, not an Oscar-bait film. Not bad for what Kael calls “pifflemaking.”

Kael’s skepticism is hardly fair to the superb supporting cast that Beatty and his co- (or main) screenwriter, Elaine May, impressively allowed to shine. “Heaven Can Wait,” whose credited cinematographer is the legendary William A. Fraker, cleverly and subtly maintains a little bit of heavenly glow over not only Beatty’s characters, but even the bad guys. It’s hardly just Warren’s performance that’s divine.

The original 1941 movie, titled “Here Comes Mr. Jordan,” was about a boxer. And Beatty apparently had the same idea. “I wanted to do it with Muhammad Ali,” Beatty told Turner Classic Movies in 2022, which is also what he told Rich for Time in 1978. He said Ali wanted to do the film but had been putting off retirement and couldn’t do it. So Beatty, who had played football in high school — “I was not bad” — changed the Joe Pendleton character to a football player and starred.

“Heaven Can Wait” uses mostly the same character names as the “Jordan” film, although the “Heaven” credits indicate it is based, like “Jordan,” on Harry Segall’s 1938 play, which actually was called “Heaven Can Wait.” The 1943 “Heaven Can Wait” film starring Gene Tierney is about a different story. Afterlife movies are popular, so it’s surprising there haven’t been more of them.

There have been “Field of Dreams,” “Ghost,” Michael Powell’s “Stairway to Heaven,” Albert Brooks’ 1991 “Defending Your Life,” which didn’t include Beatty but at least three people associated with him (Buck Henry, Shirley MacLaine and Lee Grant), and maybe the biggest afterlife movie of all, “Star Wars” (or its sequels).

What Beatty and May shrewdly realized is that, as long as the film pushes the right buttons, logic need not interfere. If he has the same body of someone else, shouldn’t he have the same brain? And how does a likely senior citizen who has never played pro football win a starting quarterback job. And why are all of the deceased people except Joe wearing suits? How did the soprano sax get to heaven? And how could neither quarterback on an NFL team have a “significant other.” You won’t even think about those things. “Heaven Can Wait” flirts seriously with shattering that fourth wall, as though Beatty’s characters are speaking directly to the camera (visually, they are not) and simply narrating the other characters’ stories.

Kael says May’s humor tends to be like “wobbly cannonballs,” sometimes they hit; other times they don’t. Most of the time, they hit. And May even spreads the gags around to the most obscure characters. Butlers hilariously try to assist Leo Farnsworth with underwear. One of the best lines is from two characters who aren’t even really part of the rest of the movie, the Rams’ previous owner, who is having instant buyer’s remorse for selling the team, and an associate, as the previous owner describes how the sale went down. “Well I asked for 67 million. And he said, ‘OK.’ ” “Ruthless bastard,” the associate agrees.

Moviemakers are fascinated by “second” characters. Peter Sellers often did several in a single movie. Tony Randall did the “7 Faces of Dr. Lao.” Superhero movies allow for the regular human being with regular problems who functions differently with a mask on. Few films though are as ambitious in this regard as “Tootsie,” in which one actor plays a struggling actor and a surprisingly successful woman. Beatty in “Heaven Can Wait” has a unique assignment: Playing the same character in three bodies, and two characters in the same body.

Beatty and May decided that, rather than having Beatty act or move like Leo Farnsworth would act or move, they will keep Joe on his one-note approach to life. This is the fish-out-of-water concept that provides the laughs until Joe can find the right body. It’s actually a 15-year forerunner of the 1993 hit “Dave,” when Kevin Kline sort of takes over the White House and is mystified by the problems he is presented. Beatty, who campaigned for George McGovern in 1972, excels here at delivering what are surely his own thoughts on right and wrong while not belaboring Joe with dogma that may turn audiences off.

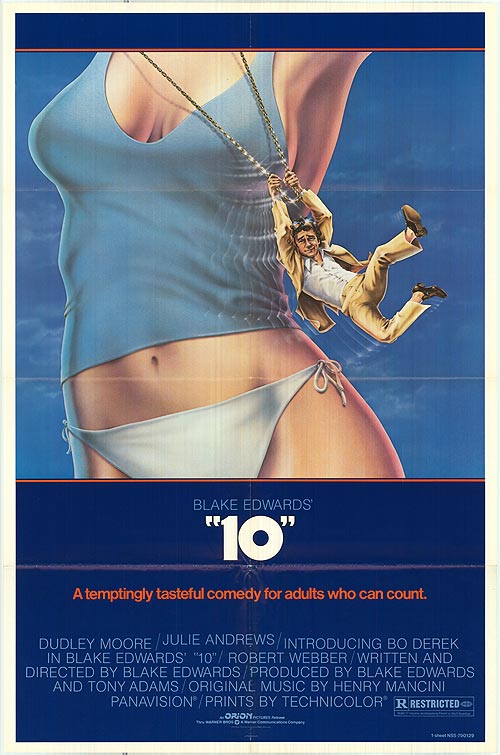

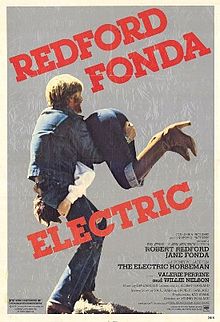

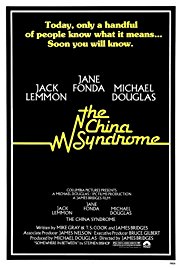

And those issues, plus Fraker’s photographic view of the Farnsworth estate, quietly make “Heaven Can Wait,” released in summer 1978, one of the first movies of the 1980s. Vietnam and Watergate aren’t factors here. Beatty just a few years earlier unleashed biting 1968 satire in “Shampoo,” but this time, he nails the future. There’s a pro-environment message, an anti-nukes jab a year before “The China Syndrome,” and a shout-out for animal rights. Other movies a year later such as “10” and “The Electric Horseman” would further cement the ’80s. Joe realizes, this inhabitation of Leo Farnsworth is a free pass. It’s a very temporary gig for Joe, whose vote is the only one that matters and who won’t have to live with the ramifications of any of his decisions. It’s the same way people can refreshingly opine on others’ problems. Beatty has fun with the nonchalance of calling out others’ faults. “Don’t you think you can do something legal and still be wrong?” he asks, not expecting an answer.

Early on, we are shown how Joe is the ultimate health nut. He eats liver-and-whey shakes and dislikes sugar and apparently most forms of frivolous entertainment. One of the team’s brass observes that “I never saw a knee like that heal without surgery, coach.” Maybe that’s a simple message about healthy eating. More likely, it’s support for a very questionable plot point — when Joe will attempt to get an obviously older body in good enough shape to be an NFL quarterback.

Logically of course, there’s a flaw in the football action — Joe as Farnsworth looks just as comfortable throwing the deep ball as does Joe as Joe. (Also, pro teams don’t practice at their stadiums.) But Beatty’s football instinct is flawless here. Playing QB in a movie (he was 41 upon release), his athletic skills are passable, like Mac Davis in “North Dallas Forty.” Beatty got permission to use the Rams’ and Pittsburgh Steelers’ name and logos, two perennial contenders of the time who, coincidentally, would actually meet a year and a half later in a real Super Bowl in Los Angeles, a matchup that prompted many — even real Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw — to wonder if the underdog Rams really were a team of destiny. “They played this movie over and over again in our hotel,” Bradshaw writes in his book Looking Deep, “and, of course, I watched it, and I am saying, ‘This is an omen! We are going to lose this game. This is an omen!’ ” (Fortunately for Bradshaw and the Steelers, life did not imitate art that day in January 1980.)

Beatty also landed a few then-recently retired Rams stars (Deacon Jones, Jack Snow, Jim Boeke, who worked for Ozzie/Harriet/Ricky Nelson and appeared on their show and later in “Forrest Gump,” and Les Josephson, an advisor to “Heaven Can Wait,” plus Super Bowl veteran Marv Fleming) to take part, and he was allowed to film his Super Bowl scenes during halftime of a real Rams game — he told TCM he had about 17 minutes to put together footage of about a half-dozen plays. He did so, accomplishing great-looking real crowd shots without resorting to special effects, although he doesn’t get real NFL game footage like “Black Sunday.”

May and Beatty smartly give Joe and his heavenly handlers a deadline — he wants to play in the Super Bowl, and the Rams are going to make it within days. A body search is conducted, starting with elite athletes, but Joe deems neither capable of quarterbacking the Rams. He is about to dismiss the prospect of occupying wealthy industrialist Leo Farnsworth except when he meets a woman and is hit by the thunderbolt.

Good movie romances may seem simple, but they still have to be earned to make us care. And “Heaven” earns it. And just when it is earned, it is lost, and the film borders on tragedy — and even sort of ends that way. Julie Christie, with a perm in “Heaven,” is not the glamourous beauty who teamed with Beatty in “Shampoo.” Like Joe, Betty Logan is a scrappy underdog overachiever who won’t be denied. Somehow, they meet in the form of Leo Farnsworth. In the sweetest approach and a steep departure from “Shampoo,” Beatty and Christie essentially never kiss — they apparently do, but their faces aren’t clearly shown. She caught his eye, but it’s as much for her determination as her appearance. There is a profound message here, that relationships are about who we are, not what we look like.

Still, it is a flaw of “Heaven Can Wait” that there are no magical moments that flip Leo and Betty from rivals into a couple. They just don’t spend enough time together. We see the way Beatty looks at Betty, but we can’t see the actual face that she is seeing. There’s material for the cynics. Does she like him because he’s wealthy, or because she made him roll over like a puppy dog?

In a film full of legendary stars, the best acting might well be from Charles Grodin, who sadly passed away in 2021 and coincidentally was in “Dave.” His scheming killer in “Heaven Can Wait,” Tony Abbott, whenever in Leo’s presence, rattles off a rare combination of lapdog sucking up and impressive business-speak. He is better than just about any real corporate flack. He is so obedient, his sins are almost forgivable. (And his main sin actually creates the situation in which Joe can meet Betty.) May has him deliver a line about race to Deacon Jones that is probably the most questionable inclusion in the movie. When Leo’s not around, Tony delivers the sight gags with Dyan Cannon, who probably felt a bit underused but screamed a lot and went with the flow and still managed an Oscar nomination.

As Max Corkle, Joe’s trusted coach and apparent only friend, Jack Warden dials down his frequent bluster of other films to serve as sensitive listener and conduit to the friend he thought he had lost. Max does not have the same gift as Whoopi Goldberg’s character in “Ghost” — he can’t see the decedent and, at first, visually believes he’s talking to Leo Farnsworth. There is a slightly frustrating and of course predictable exchange in which viewers have to wait moments for Max to stop insisting that Farnsworth has gone crazy. Once that’s past, Warden beautifully shifts to the sympathetic friend who knows, however wild and cool this whole situation seems, that Joe is still fighting a very uphill battle to regain any semblance of the life he knows and loves. Then once Max starts to believe it has happened (at the expense, curiously, of a fellow player), Joe fades away, and Max realizes the friend he knew is truly gone. People may not die in “Heaven Can Wait,” but there is loss.

The Oscars are hardly perfect. They handed Warden a best supporting actor nomination over Grodin. Warden lost to Christopher Walken of “The Deer Hunter” (Grodin wouldn’t have beaten Walken either), while Cannon lost to Maggie Smith of “California Suite.” Fraker lost to Néstor Almendros of the landmark “Days of Heaven.” In the Oscars, “Heaven Can Wait” and other films were facing formidable competition from a couple of Vietnam heavyweights, “The Deer Hunter” and “Coming Home.” Even without much hardware, a rom-com farce seriously competing with that type of material is no disappointment. Those two Vietnam films were haunted by the recent past; Beatty’ work foreshadowed a different American focus to come in the ’80s. Beatty may have lost the Academy Awards battle, but he won the pop culture war.

Beatty the actor lost to Jon Voight in “Coming Home.” Beatty and Buck Henry lost out for best director Oscar to Michael Cimino of “The Deer Hunter,” while Oliver Stone (“Midnight Express”) topped Beatty and May for adapted screenplay. “The Deer Hunter” prevailed as best picture. The lone “Heaven Can Wait” Oscar was won by the team of Paul Sylbert, Edwin O’Donovan and George Gaines for art direction/set decoration. “Here Comes Mr. Jordan,” by the way, got nominations for best picture/director/actor/supporting actor/writing/screenplay/cinematography and won two.

Of course, the physics can’t all add quite up. Did Tom Jarrett enter heaven for a few moments after his injury, then recombine with Joe Pendleton in Jarrett’s earthly body? Does Jarrett now like the same food and music as Joe as well as the same type of women? It seems that all Joe’s untimely death did was preserve life for Jarrett, who has no idea why he’s alive. As Roger Ebert points out, “What good is it living another half century, if it’s as someone else?”

Whichever body he ends up in, Joe, according to the movie, is still not done. We’re told early on that he was actually due to arrive in heaven at 10:17 a.m., March 20, 2025. So Tom Jarrett should be grateful for his extra 47 years — but as we’ve seen, mistakes and complications can happen.

Though his movie is very much about what happens in the afterlife, there doesn’t seem to be any indication that Beatty had screenings and discussions with religious leaders. Maybe the movie’s most important figure is the venerable Mr. Jordan. Beatty told Turner Classic Movies that legends were considered. “I think I did talk to Cary, and, uh, he did not want to do it,” Beatty said. James Mason, of the heavenly voice, appeared in far more bad or obscure movies than good ones. His Mr. Jordan is described as some sort of middle manager, but his command of destiny suggests he is playing God and that this is what God may be like: a firm plan but a willingness to help us out along the way.

4 stars

(March 2024)

“Heaven Can Wait” (1978)

Starring

Warren Beatty

as Joe Pendleton

♦

Julie Christie

as Betty Logan

♦

James Mason

as Mr. Jordan

♦

Jack Warden

as Max Corkle

♦

Charles Grodin

as Tony Abbott

♦

Dyan Cannon

as Julia Farnsworth

♦

Buck Henry

as The Escort

♦

Vincent Gardenia

as Krim

♦

Joseph Maher

as Sisk

♦

Hamilton Camp

as Bentley

♦

Arthur Malet

as Everett

♦

Stephanie Faracy

as Corinne

♦

Jeannie Linero

as Lavinia

♦

Harry D.K. Wong

as Gardener

♦

George J. Manos

as Security Guard

♦

Larry Block

as Peters

♦

Frank Campanella

as Conway

♦

Bill Sorrells

as Tomarken

♦

Dick Enberg

as TV Interviewer

♦

Dolph Sweet

as Head Coach

♦

R.G. Armstrong

as General Manager

♦

Ed V. Peck

as Trainer

♦

John Randolph

as Former Owner

♦

Richard O’Brien

as Advisor to Former Owner

♦

Joseph F. Makel

as Haitian Ambassador

♦

Will Hare

as Team Doctor

♦

Lee Weaver

as Way Station Attendant

♦

Roger Bowen

as Newspaperman

♦

Keene Curtis

as Oppenheim

♦

William Larsen

as Renfield

♦

Morgan Farley

as Middleton

♦

William Bogert

as Lawson

♦

Robert E. Leonard

as Board Member

♦

Joel Marston

as Board Member

♦

Earl Montgomery

as Board Member

♦

Robert C. Stevens

as Board Member

♦

Bernie Massa

as Coliseum Security Guard

♦

Peter Tomarken

as Reporter

♦

William Sylvester

as Nuclear Reporter

♦

Lisa Blake Richards

as Woman Reporter

♦

Charlie Charles

as Highwire Performer

♦

Nick Outin

as Chauffeur

♦

Jerry Scanlan

as Hodges

♦

Jim Boeke

as Kowalsky

♦

Marvin Fleming

as Gudnitz

♦

Deacon Jones

as Gorman

♦

Les Josephson

as Owens

♦

Jack T. Snow

as Cassidy

♦

Curt Gowdy

as TV Commentator

♦

Al DeRogatis

as TV Color Analyst

Directed by: Warren Beatty

Directed by: Buck Henry

Written by: Elaine May (screenplay)

Written by: Warren Beatty (screenplay)

Written by: Harry Segall (based upon a play by)

Producer: Warren Beatty

Executive producer: Howard W. Koch Jr.

Executive producer: Charles H. Maguire

Music: Dave Grusin

Cinematography: William A. Fraker

Editing: Robert C. Jones, Don Zimmerman

Casting: Pat Mock

Production design: Paul Sylbert

Art direction: Edwin O’Donovan

Set decoration: George Gaines

Costumes: Richard Bruno

Makeup and hair: Lynda Gurasich, Lee Harmon

Unit production manager: Charles H. Maguire