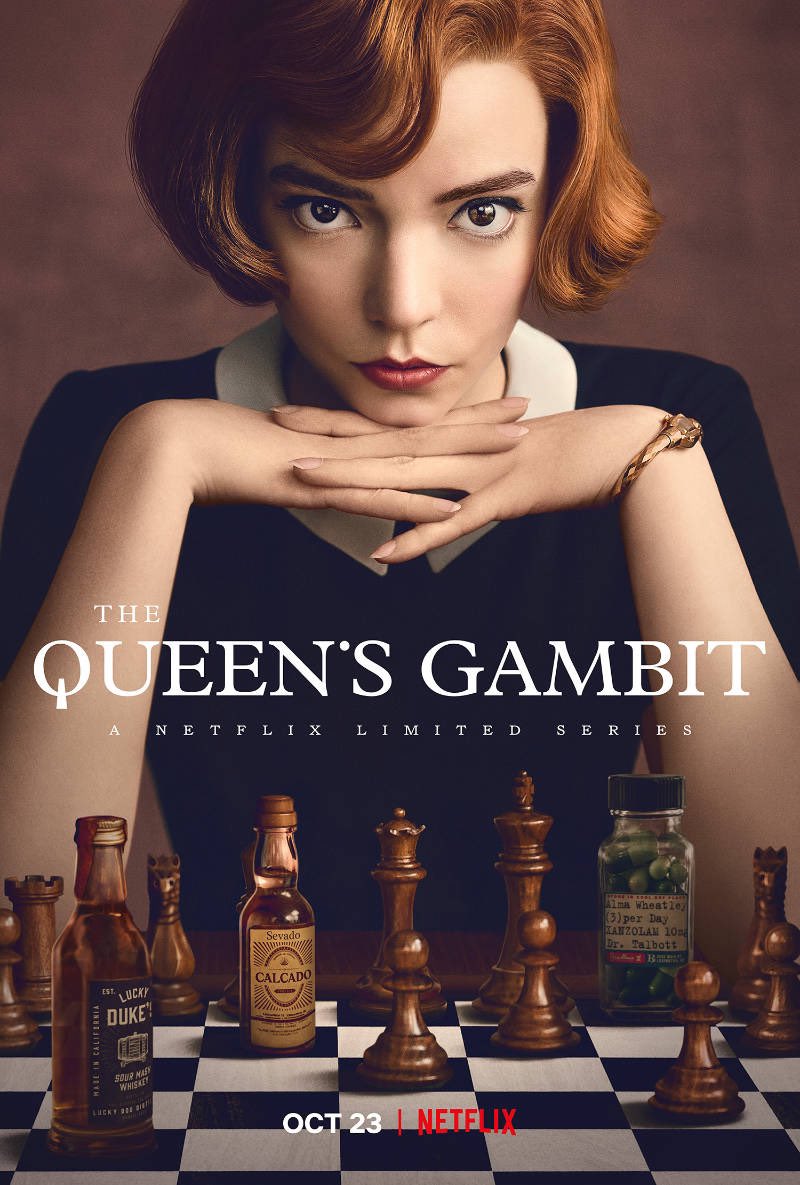

‘Queen’s Gambit’ is another successful slap at the ’60s

“The Queen’s Gambit,” a 2020 Netflix miniseries, loves the cars of the 1960s.

And a lot of the clothes.

Aside from that, not much else.

“Gambit,” a creative, fictional alternative to the Bobby Fischer story based on the 1983 novel by Walter Tevis, is less interested in rook-knight revenge than in settling some social scores. Viewers could bring a checklist of Subjects Ignored in 1950s/1960s Television and Film and pretty much mark an X in every box. Mental health, feminism, race, substance abuse, LGBTQ. All provide a curious contrast with the stately, traditional, white-male-dominated field of chess, in which the greatest off-board drama historically is about possible defections (think 1984 Oscar winner “Dangerous Moves”).

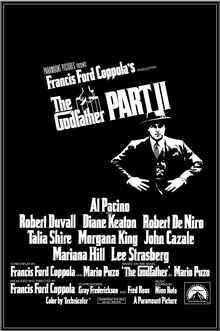

To its credit, “Gambit” does not dwell on typical cliches of young people listening to Elvis or attending Vietnam rallies. It also realizes that directing its cameras at chessboards long enough to absorb the last move will appeal to only chess players. To fill the visual gaps, its choice is to depict a couple of characters chugging booze and pills as though they were having popcorn and Coke at “Dr. No.” Not only are these scenes cartoonish, they flip on and off like a light switch. Beth and her adoptive mother are little more than party pals. In reviewing the 1991 film “The Doors,” Roger Ebert wrote, “Watching the movie is like being stuck in a bar with an obnoxious drunk, when you’re not drinking.” Beth at times must be more drunk than Nicolas Cage in “Leaving Las Vegas” and more serious than Al Pacino in “The Godfather: Part II,” in which, curiously and coincidentally, Michael Corleone also knows something about a Sicilian defense.

It’s not an overstatement to say that the success of such a character-driven drama as “Gambit” comes down to the actor. Anya Taylor-Joy, who bears a tiny resemblance to a young Shelley Duvall and whose specialty has been horror films, has a great look. Beautiful and charming on the outside, with a hint that there might be something dangerous within. Too often, she is as robotic as her chess moves, almost a human-like Alexa in the other characters’ worlds. Whether it’s a win or loss, her demeanor is the same. Others seem to be more emotionally invested in her winning than she is. Why does she play chess at this level, forgoing sleep and other elements of a “normal” life to review her old games? The obvious answer is, “She’s so good at it.” That explains why she joins tournaments. It does not explain how she might beat Borgov, who feels he is the guardian of the soul of his country with every move. Is she playing to prove a point, settle a score, make a living, or to enjoy the attention? We’re told several times, “She wants to win.” Who doesn’t?

Many high-level chess matches don’t end in people knocking over their kings, but in draws. “Gambit” is not interested in draws. Nevertheless, the chess community approved of the show’s depictions. It’s doubtful the substance-abuse community would have the same reaction. Whether Beth even qualifies as “addicted” to anything is debatable. Her behavior is virtually always impeccable. “Gambit” suggests that tranquilizers and alcohol offer Beth a rare insight into the game (sort of like what the Beatles said in the mid-’60s about mind-altering drugs) and are less dangerous to her than a few candy bars ... they might prevent her from waking up in time for a scheduled appearance. She beats this indulgence not from intensive therapy but from a few bits of encouragement from her friends. That’s maybe a major reach, but at least it’s not quite as bad as John Nash in “A Beautiful Mind” simply ignoring his schizophrenia.

Scott Frank, the production’s writer-director, says, “It’s not about a game, it’s about the cost of genius.” His adaptation indicates that whatever’s going on in Beth’s mind that reads chessboards like no others also craves unhealthy doses of tranquilizers and alcohol. While there may be evidence that Beth would spiral out of control if her matches were canceled, “Gambit” never demonstrates why attempting to play chess at a high level is “costing” Beth her mental health.

Brilliant film characters struggling with psychological trauma have a strange way of attracting no attention. Beth, like Will Hunting, despite a 1-in-a-billion intellectual gift, attracts no attention from high school teachers or counselors. What are her grades? It would figure that someone of higher academic credential than Mr. Schaibel would notice this person’s brain. Yet taking a physics class in high school would only cause more work for the screenwriters, who are more interested in skipping school than their protagonist is.

In a telling comment, Taylor-Joy says in Netflix’s “Creating the Queen’s Gambit” that “It’s not a physical loneliness that she’s suffering from, it’s an emotional and intellectual one.” But Beth’s got two problems that a therapist would likely be far more interested in — she might be genetically inclined to have the same troubles as her mother, and she has experienced significant abandonment at young ages. Evidently, playing chess is even more therapeutic than John Nash’s code-breaking, and the ghost images that Beth sees (the impressively visual chess pieces in the ceiling) are only 100% helpful to the big picture.

“I do think that she’s juggling a very fine line of like, Am I insane, or am I a genius,” Taylor-Joy says. But there’s nothing in these 7 parts to suggest Beth is crazy.

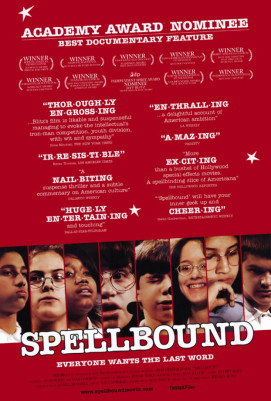

One idea strongly implied in “The Queen’s Gambit” is that, as in “Spellbound (2002),” there is no such thing as too much studying. “Spellbound,” a documentary about diligent, by-the-book preparation, differs with typical competition dramas in which the hero is usually someone with an unorthodox style whose best moments come from winging it. But maybe knowing too much about Borgov is a serious liability, that he expects others to study his games and then reinvents his play to outmaneuver them. There are a finite amount of combinations for a chess board. Mastering them all, to the extent it’s possible, should be the goal, though “Gambit” suggests the psychology is equally important, that guessing what your opponent will do in a situation is the only way to achieve more than a draw.

Beth enjoys the money she makes but isn’t financially motivated. “Gambit” says that the chess scene of the 1960s (outside of the Soviet Union) was basically no-income, a hobby in which the prizes tend to be financed by the entry fees of other players and the only spending comes from peripheral groups with no connection to the game. Yet here is Beth on the cover of national magazines and newspapers. She appears to be, with the possible exception of Benny, the only person in the United States able to make a (lackluster) living playing chess. And where in the world is the leadership of the national chess system, which must be nonexistent. Beth apparently has to schedule all of her own tournaments and wait for invitations from around the world.

Financial matters in “Gambit” are a fail. Whatever Beth needs, she gets from her chess friends. An obstacle emerges when Beth declines much-needed funding for a trip abroad; a statement that she must’ve expected to be part of the deal suddenly is enough to derail her dream of playing Borgov and the other Soviets in Moscow. That wrinkle was invented to deliver a message against church influence of the 1950s and ’60s and provide a re-entry point for Beth’s reliable childhood friend, Jolene, whose life actually sounds possibly better than Beth’s. Jolene’s got a good job and enough money for law school and a bright future. Would Beth make the same financial sacrifice for Jolene? There’s enough there to say yes.

“Gambit” may have viewers believing that any chess player over 20 is past his prime, but the collection of characters sends a healthy message of not judging a book by its cover. A dubious figure in Beth’s orbit is Bill Camp’s Mr. Shaibel. He could be Beth’s safety valve within the institution or her biggest nemesis. But he’s nothing but a way station. He accepts Beth not because he wants to enlighten a child, but because she forces him to. He is not the driver of the institution but perhaps a victim of it. He expresses little joy in her success, mostly astonishment. The location of his chessboard suggests a number of things, not all of which mesh with the story. Is he playing chess on company time? Is this game so dubious that people should be afraid to play it out in the open? Does he have reason to be skeptical of every girl in this facility? Mostly, “Gambit” installs Mr. Shaibel to demonstrate the sexism of a “boy’s game.” He doesn’t think she belongs at his table because she’s a girl. Beth’s other male opponents all quickly figure out and respect that she is good; it’s Mr. Shaibel who takes the longest to come around.

But the disaster of a character is Millie Brady’s Cleo, however charming. Cleo is the correct version of the sorority girls that Beth spurned earlier, a beautiful person who understands and testifies that real beauty is within. Except that in her limited time, she can’t demonstrate it, only say it, and it’s necessary to wonder for a while if she’s a KGB plant.

The series’ most uplifting moments occur in a conference call. The strength and permanence of this association is tested by the question, Did this group do the same thing for Benny’s foreign matches? Beth’s field of potential partners is at two, who may be realizing that they’ll only be able to share her, on an intellectual level.

Chess, though still widely played, is surely an old-school activity in an era of Digital Everything. Its peak in pop culture had to be the 1970s, when Bobby Fischer briefly dented the Russian fortress that commandeered the pastime, at least at the highest international levels. Nowadays, it would be shocking if a person on the street could name the current world champion. “Gambit” will begin to rally when it steps over its ludicrous depictions of substance abuse and into the Cold War. The series takes place before Fischer’s emergence, probably to avoid contrasting his career with Beth’s and also to take the juiciest possible bite of 1950s stereotypes. But “Gambit” in 2020 recognizes a huge part of Fischer’s appeal and fans the remaining embers of it: Hey, we can beat the Russians at their own game!

Unpredictability is usually a requirement for successful drama. “Gambit” is highly predictable, and hints at more complex storylines seem to be dropped just in case this series got picked up for an entire “season,” if that’s even the correct term now. She has two fathers somewhere out in the world, each apparently oblivious to her fame. There are rumors of a possible defection. A 13-year-old vows to be world champion in a few years, then is never heard from again.

“The Queen’s Gambit” is not a deep dive into chess or mental illness. It’s a body-slam of the 1950s and ’60s, for not being fair to women or race relations or mental illness and hiding addiction problems and forcing young people to conform to religious orthodoxy and silencing with mind-altering drugs the upstarts who might question the corrupt system. Compared with that, Borgov is a piece of cake. Mate.

3 stars

(March 2021)

“The Queen’s Gambit” (2020)

Starring:

Anya Taylor-Joy

as Beth Harmon ♦

Chloe Pirrie

as Alice Harmon ♦

Bill Camp

as Mr. Shaibel ♦

Marcin Dorocinski

as Vasily Borgov ♦

Marielle Heller

as Alma Wheatley ♦

Thomas Brodie-Sangster

as Benny Watts ♦

Moses Ingram

as Jolene ♦

Harry Melling

as Harry Beltik ♦

Isla Johnston

as Young Beth Harmon ♦

Janina Elkin

as Borgov’s Wife ♦

Matthew Dennis Lewis

as Matt ♦

Russell Dennis Lewis

as Mike ♦

Patrick Kennedy

as Allston Wheatley ♦

Christiane Seidel

as Helen Deardorff ♦

Jacob Fortune-Lloyd

as D.L. Townes ♦

Akemnji Ndifornyen

as Mr. Fergusson ♦

Annabeth Kelly

as Five-Year-Old Beth ♦

Dolores Carbonari

as Margaret ♦

Zoé Höche

as Girl #1 ♦

Andruscha Hilscher

as Russian / ... ♦

Iskander Madjitov

as Another Russian ♦

Rebecca Root

as Miss Lonsdale ♦

Clement Guyot

as Tournament Director ♦

Frederic Stromenger

as Man In Elevator / ... ♦

Sophie McShera

as Miss Graham ♦

Katherine Towe

as Girl #2 ♦

Mia-Luisa Schrader

as Girl in Elevator ♦

Laura Danne

as Jolene’s Friend ♦

Nina Herzberg

as Margaret’s Friend ♦

Richard Waugh

as Mr. Bradley ♦

Marian Meder

as Mr. Espero ♦

Frieda Raab

as Apple Pi Girl #1 ♦

Sergio Di Zio

as Beth’s Father ♦

Emma Henker

as Giggling Girl #1 ♦

William Horberg

as Toby ♦

Alva Schäfer

as Apple Pi Girl #3 ♦

Marlene Leinemann

as Apple Pi Girl #4 ♦

Matteo Vinogradov

as Borgov’s Child ♦

Max Krause

as Levertov ♦

Ryan Wichert

as Hilton Wexler ♦

Eloise Webb

as Annette Packer ♦

Millie Brady

as Cleo ♦

Rebecca Dyson-Smith

as Stewardess ♦

Lucy Ella von Scheele

as Apple Pi Girl #2 ♦

Felice

as Marceno / ... ♦

Philipp Droste

as Tournament Director

Nikolai Jegorow

as Russian Teacher ♦

Daniel Brunet

as Man at Sign in Table ♦

Maximilian Frisch

as Young Borgov ♦

Sam Gilroy

as Tim ♦

Sophia Frank

as Barbara ♦

Raphael Keric

as Someone ♦

Adrian Hagenguth

as Middle Aged Man ♦

Salber Lee Williams

as Eileen ♦

Alexander Albrecht

as Manfredi ♦

Ilja Roßbander

as Rudolph ♦

Simon Jensen

as Alec Bergland ♦

Jeremy Mockridge

as Friedman ♦

Frederik Funke

as Third Opponent ♦

Alec Dahmer

as Teenage Reporter ♦

Simon Jansen

as Alec Berglund ♦

Samantha Soule

as Miss Jean Blake ♦

Uke Bosse

as Another Reporter ♦

Ben Gageik

as Weiss ♦

Pia Schlipphak

as Mrs. Macarthur ♦

Pablo Scola

as Manuel ♦

Drew Doyle

as Cop #1 ♦

Dmitri Ford

as Russian Reporter ♦

David Gorelik

as Boy ♦

Peter Gilbert Cotton

as Lutheran Minister ♦

Paul Johnston

as Cop #2 ♦

Frédéric Vonhof

as Paris Waiter ♦

Rahul Chakraborty

as Vendor ♦

Jenny Galloway

as Matron ♦

Lily Lesser

as Girl in Lunchroom ♦

Charlotte Lucas

as Mrs. Dodge ♦

Nicky Goldie

as Mrs. Blocker ♦

Paul Walther

as Vendor #2 ♦

Maximilian Diehle

as French Guy #1 ♦

Maria Heinsch

as Giggling Girl #1 ♦

John Schwab

as Mr. Booth ♦

Lukas Huber

as French Guy #2 ♦

Juri Padel

as Russian Limo Driver ♦

Evgenij Verenin

as Russian Radio Announcer ♦

Konstantin Frank

as Tournament Director ♦

Jennifer Haas

as Mary-Sue ♦

Marja Haensch

as Giggling Girl #2 ♦

Marcus Loges

as Luchenko ♦

Alberto Ruano

as Director ♦

Rosalie Craig

as Librarian ♦

Jan Nahuel Häfliger

as Alberto Diaz ♦

Tim Kalkhof

as Roger ♦

Ben Moor

as Mr. Hume ♦

Frederick Schmid

as Laev ♦

Colin Stinton

as Chennault ♦

Michel Diercks

as Duhamel ♦

Elvis Nowatzki

as Margaret’s Boyfriend ♦

Ben Posener

as Guy ♦

Matthew Rowsell

as Mowing Boy ♦

Adrian Zwicker

as Diedrich ♦

Dora Zygouri

as Girl in Line ♦

Louis Ashbourne Serkis

as Girev ♦

Hugo Grimm

as Hellstrom ♦

William von Tagen

as Other Player ♦

Vlad Chiriac

as Shapkin ♦

Anna Hauss

as Singer at Piano ♦

Jonjo O’Neill

as Mr. Ganz ♦

Till Trenkel

as Flento ♦

Josepha Walter

as Local Makeout Girl ♦

Ricky Watson

as Paul Tix / as ♦

Marc Bergemann

as Local Makeout Boy ♦

Juozas Budraitis

as Old Man ♦

Tatsu Carvalho

as Doctor ♦

Maddie Holliday

as Shirley Munson ♦

Tiit Lilleorg

as Second Old Man ♦

Andreas Muñoz

as Manager ♦

Bruce Pandolfini

as Ed Spencer ♦

Alexander Berdichevsky

as Charles Levy ♦

Ivan Gallardo

as Farmacia Man ♦

Steffen Mennekes

as Cullen ♦

John Hollingworth

as Randall Foster ♦

Daniel Holzberg

as Cooke ♦

Nelly Russakowa

as Samantha ♦

Johannes Franke

as Sizemore ♦

Anton Krymskiy

as Russian Waiter ♦

Ben Brener

as Young Russian Boy ♦

Jérémie Galiana

as Klein ♦

Jonathan Failla

as Reporter In Lobby #1 ♦

Marc Zwinz

as Reporter In Lobby #2 ♦

Frank Streffing

as Reporter In Lobby #3 ♦

Daniel Montoya

as Reporter In Lobby #4 ♦

Dmitriy Frid

as Russian reporter ♦

David Masterson

as Newsreel Reporter

Directed by: Scott Frank

Created by: Scott Frank

Created by: Allan Scott

Teleplay by: Scott Frank

Based on the novel by: Walter Tevis

Producer/executive producer: Scott Frank

Producer: Mick Aniceto

Producer: Marcus Loges

Executive producer: Allan Scott

Executive producer: William Horberg

Co-producer: Uwe Schott

Associate producer: Susan Hsu

Producer’s assistant: Pia Schlipphak

Creative executive: Laura Delahaye

Creative executive: Blair Fetter

Music: Carlos Rafael Rivera

Cinematography: Steven Meizler

Editing: Michelle Tesoro

Production design: Uli Hanisch

Art direction: Kai Koch, Brendan Smith, Daniel Chour, Thorsten Klein

Set decoration: Sabine Schaaf, Ingeborg Heinemann

Costume design: Gabriele Binder

Makeup and hair: Daniel Parker, Jenna Smith, SJ Teasdale, Abra Kennedy, Silvia Platsis

Unit manager: Timo Dobbert

Move manager: Em Hipp

Unit production manager: Marc Grewe

In memory of: Iepe Rubingh