‘50/50’ — when the

Worst Therapist Of All Time

has a phone number

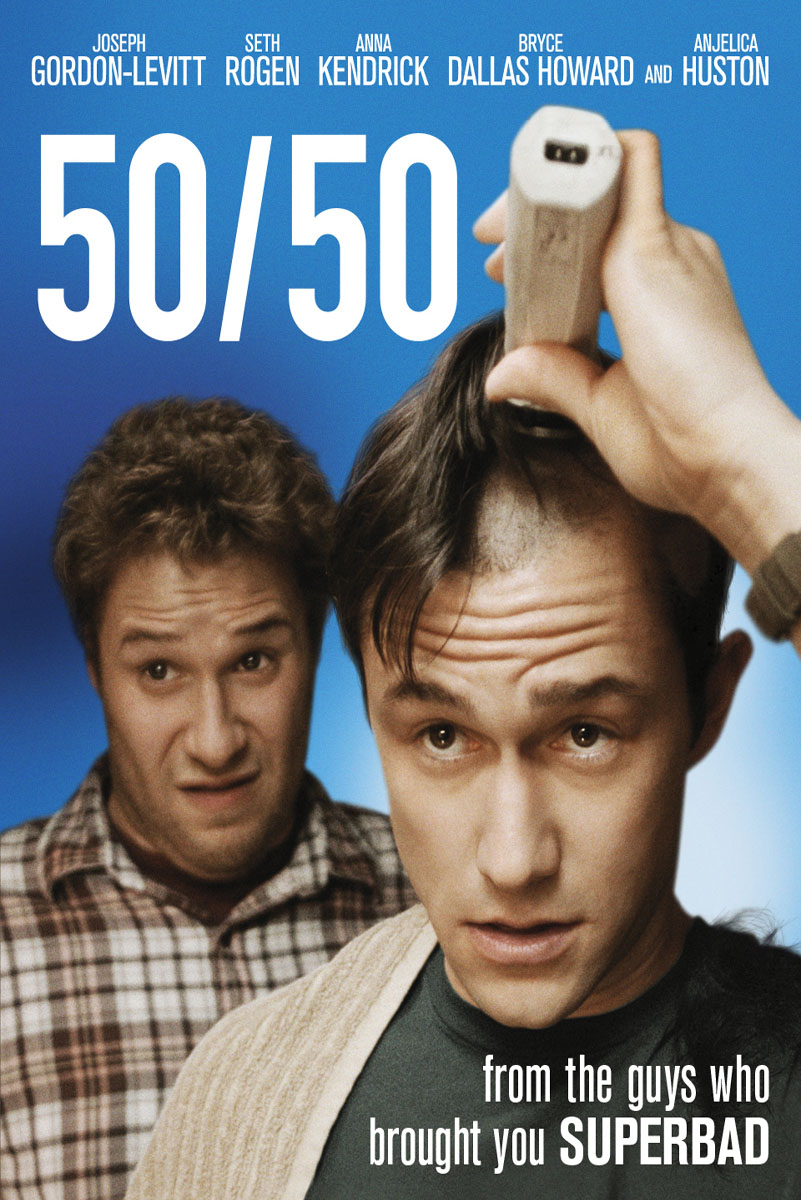

“50/50” is a movie about reacting to things beyond our control. Disappointingly, the cancer-stricken protagonist, played by the extremely capable Joseph Gordon-Levitt, has learned nothing by the end of the film except that he is damn lucky.

“50/50,” as those numbers imply, has a heart, but no brain. Actually that’s the best way to describe its most important character, Katherine, the psychologist/social worker/therapist-in-training who’s available and not much more.

There just isn’t enough here for a memorable movie; one wonders how it would’ve even been deemed makeable without the punch lines of Seth Rogen, who saves a dysfunctional cast. The climactic statement is delivered by a colorless surgeon, who seems the real difference-maker in this picture even if she’s only given probably less than a minute of screen time.

Medical drama, evidenced by countless powerful TV shows and films, is reliable material. Writer Will Reiser takes a risk opting for laughs. But that’s his specialty. Reiser, encouraged by his friend Rogen, wrote the story from his own cancer experience. It’s a sincere effort. The fiction he added is as ineffective as Rachael’s painting.

Reiser’s script suffers from the same real-life, binary-outcome expectation of James Franco’s Aron Ralston in “127 Hours.” We know there will be a few scars. In each film, after about a half hour, we’re just waiting to know, is he gonna make it. “50/50” gives itself a greater challenge than “127 Hours” because Adam’s problem is rightly deemed beyond his control; he does not have the option of resourcefulness, only hope.

Reiser settles on a strangely watered-down compromise between “Brian’s Song” and “Scrubs.” There are enough gags to assure early on what we will ultimately hear from Adam’s surgeon. It’s hard to find Adam in a seriously grim moment. Or in serious discomfort. His pain stems more from exasperating acquaintances than a frightening disease. The possible onset of a tear is too much for this film. Adam’s able to get high during chemotherapy and see the humor in old people being wheeled in gurneys and barely able to walk. If you weren’t sure whether to laugh or cringe, you’re not alone.

Oddly enough, in a movie that needs a jolt of invented drama, it’s the woeful therapist, Katherine, who is fictional, something professionals will be relieved to know. She is an upgrade only to Rachael, Adam’s abominable girlfriend at the beginning of the film. Reiser said his actual therapist was a woman in her 50s. Here we’ve got legitimate artistic license converting lemonade into a lemon.

Therapy movies thrive on the resistance between professional and patient, reluctant protagonists being dragged into sessions. This creates healthy drama, the therapist fighting through a wall. “50/50” is weak in that Adam’s visit to Katherine seems perfunctory. He only appears to be attending because of the suggestion, and conversational shortcomings, of his physician. Adam is not distraught, nor is he opposed to counseling. The script needs to pick one or the other.

It’s possible Adam could actually create effective drama here by vigorously seeking therapy after finding his friends and relatives difficult to deal with. But that’s a tall order for Reiser, whose script puts Adam in Katherine’s office at the 18-minute mark. (Will Hunting meets Sean Maguire after 37 minutes, in a longer film.) In general people are in therapy because of bad things. You don’t really want to be there. It’s a last resort. The resistance angle makes the most sense. But Adam’s an enlightened guy willing to take advantages of all the resources the hospital can offer. He’s so enlightened as to make these sessions drama-free.

Katherine, played by charming but overbooked Anna Kendrick, is so inept, it’s troubling that a sharp guy like Adam would fall for her. Her interest in him seems little more than pity. If Kendrick, already an Oscar nominee in her 20s, had more stature, she would’ve rejected this preposterous role or demanded changes. That’s what the great ones sometimes do. This script hinges on her character. At best Katherine represents not a powerful love story but incompetence in the health-care system, the notion that counseling is ineffective or useless. Adam, a seriously ailing man, is first given an ominous physician, then assigned to this professional-in-training who crosses the ethical boundaries before her dissertation is even started. If the cancer isn’t going to kill Adam, depression might.

Probably the strongest angle for the “50/50” premise would be a statement about bad breaks. There is unrealized potential here. You have a character who is doing everything right, living a low-risk lifestyle, even describing driving as “incredibly dangerous,” only to be hit with a massive problem. In accepting this situation beyond his control, he could begin to realize how to improve the things within his control. There is an open-ended question about the merits of playing by the rules. Should we all chuck our emphasis on values when realizing that they can’t protect us from a crisis such as Adam’s? Notice Adam’s approach to sex is constant throughout the film. He wants something meaningful and mostly doesn’t succumb to Kyle’s temptations. “50/50” barely shows us, almost in a grudging way, that our outlook, the things that make us tick, don’t change when we’re ill; the human personality is somehow impervious to some of the mightiest uncontrollable forces.

Opening scenes show us exactly what a risk-free person Adam is. He jogs the streets of Seattle, healthy and vigorous. He actually stops at a stoplight with no cars present as another jogger breezes by. Then he grabs his back.

Maybe it’s just a typical backache. After all, he’s a healthy jogger.

Denial is supposed to be the first of the 5 stages of grief. Adam’s disbelief, to the extent there is any, is condensed into maybe a couple sentences in his doctor’s office. “I don’t smoke, I don’t drink, I, you know, recycle,” he says, before fully grasping the gravity of the situation.

Rarely would more denial be recommended. Yet Adam seeks no second opinions or information about alternative treatments. He has been told by an absurdly cold doctor that he has an extremely rare disease. He is even compelled to turn to the Internet to find out his purported survival chances. There is a necessary fine line we all must find between disbelief and needing more information. Adam is surely in the latter camp but doesn’t know it.

One thing Adam discovers is that when you have a complicated illness, you deal with doctors of varying degrees of likability. His primary physician is so lacking in empathy that he can’t even speak directly to Adam, but into a microphone, explaining, “MRI suggests a massive intradural malignant schwannoma neurofibrosarcoma,” or as we learn, after the request for clarity, “It’s a malignant tumor.” Yet we’re not going to exit this place without warmest regards for Adam’s surgeon, Dr. Walderson, who takes her time to reveal the most important news.

Depicting a cancer patient, it’s hard to ignore the hospital, and visuals-challenged director Jonathan Levine surely doesn’t. Hospitals are very important places. However, they are not places anyone wants to go, at least generally not for laughs. If we’re not worried about grim death, we’re bored. The “50/50” hospital scenes often feel like a stint in the waiting room. Nothing to do here but sit for a while, crack a few jokes, pass the time.

Ideally in this film, given that Katherine is only a graduate student, Adam could be the big success that puts her over the top. But Katherine just needs a boyfriend. She is so incompetent that, despite having just 2 other patients, she doesn’t know that she has an appointment with Adam. He walks in while she is eating on her couch, completely unprepared, and he tells her, “you seem a little young to be a doctor.” She concedes she is not there yet, but assures that her handling of him “will be part of my dissertation.” Yes, young health professionals do need to receive training; patients don’t have to be lab rats.

The scenes in Katherine’s office are neither funny nor touching nor powerful. “Silly” is an apt description. “This must be incredibly difficult ... How do you feel,” she says, describing Adam’s sense of calm as a “really common symptom” of his cancer she knows nothing about; a “kind of numbness.”

“Maybe today we just start with some simple relaxation exercises,” is her opening; “just humor me.”

Yet she’s the one on the defensive throughout their sessions. “I’m not trying to make you freak out,” she will tell him. “I don’t need you to take care of me. I’m trying to take care of you ... I’m trying to make you feel more at ease.”

At one point she will concede, “This job is really hard.”

The turning point comes when Katherine finally learns what viewers have long grown weary of, that Rachael is out of the picture. “Adam, do you wanna talk about this,” Katherine asks, before telling Adam the most important thing she will ever tell him: “I just broke up with somebody recently myself ... we actually shouldn’t be talking about it.”

And then in one of those self-fulfilling prophecies, there’s the phone-number offer.

The best Katherine can do is recognize that Adam’s mother, Diane (Anjelica Huston), has no one to talk to. Diane is just one of the film’s half-dozen or so scattershot, unharnessed supporting characters. This is not unnatural. All of us deal closely with people who have no connection to each other. Some are more comfortable to deal with in certain situations than others. Most of the characters in “50/50” deal exclusively with Adam and aren’t the least bit interested in hanging out with each other.

“Ordinary People,” a superior, albeit semi-grim, film, also throws a variety of characters at a young, suffering person, but in a most impressive way. They represent layers of difficulties in returning to society. Adam by contrast is dealing in small potatoes from his acquaintances. A girlfriend he should’ve dumped long ago can’t deal with his situation. (She frankly admits, “We had problems long before you got sick.”) Mom just wants to help and really is no trouble at all. Kyle is perhaps overcompensating in the We-Should-Still-Have-Fun Department. Adam’s boss seems oblivious. The other chemotherapy patients succeed only in introducing Adam to marijuana (there is a curious Rogen-esque message here that poses the question of whether chemotherapy patients at a hospital can harm themselves during treatment if stoned) and (only briefly) illustrating how true love knows no medical bounds. One of those patients, Lombardo, is oddly gruff, calling out Adam’s girlfriend in absentia and somehow scolding him for asking how their friend died; “What does it matter, his heart stopped.” (Contemplating whether Lombardo enhances Adam’s appreciation of life, or diminishes it, is quite an exercise.)

Health problems tend to be one of the 2 major sources of life’s stress. The other, perhaps even worse, is money. Somehow, financial considerations never surface in the slightest in “50/50.” Will Adam be spared large out-of-pocket expenses for his extensive treatment? Apparently yes. Is Katherine a bonus of the health plan? There is nothing about an hourly rate. Can he keep working? No sign of a problem there.

Money is just one reason “50/50” feels sanitized. Adam’s condition is high-risk but not highly stomach-churning. Real-life cancer is far messier. One scene depicts a late-night vomit; otherwise there appear to be no changes to his diet, no unusual difficulties in the bathroom. He can date and meet girls. There is no agony here, unlike the recent and much different take on illness-coping, “Amour.”

The movie is far more of a star vehicle for Rogen than Gordon-Levitt, described in interviews as a replacement for James McAvoy, who had to give up the role over personal matters. Gordon-Levitt is unable to paint Adam with any kind of edge; this film will be most memorable for his co-star. Since “The 40 Year Old Virgin,” Rogen has carved a highly effective niche as a raunchy stoner who may be uncouth but always has his buddy’s back. The shtick is that sex and drugs are desired; everything beyond that is traditional values. Without much else in this plot, Reiser and Rogen are forced to kick this routine into overdrive, so that Kyle is discussing yeast infections at a coffee shop, shaving pubic hair, taking down cheating girlfriends. A meltdown in a car seems phony, and a desperate reach. It’s unclear in “50/50” how anything Kyle does could be considered therapeutic. He encourages Adam’s pot-smoking (but is not the one who instigates it), and helps set him up with sex. And yes, he finishes off the bad girlfriend — who shouldn’t be along this far in the movie anyway — in one of the film’s most creative moments, a knife-throwing demonstration. It only takes an hour of the movie to get rid of her, after a bizarre porch kiss that utterly no one wants, least of all the viewer.

But while Kyle is able to give Rachael the boot, he’s strangely irrelevant in bringing Adam and Katherine together. In “Virgin,” Rogen admirably sees through his own priorities to recognize that Andy needs Trish. In “50/50” he is barely given a chance to know Katherine, who hopefully wouldn’t have impressed him with her credentials anyway.

Making people such as Kyle and Katherine and perhaps Diane as worthy of discovery is something Reiser likely could’ve accomplished. Mostly failing that, he’s utterly behind the 8-ball demonstrating — in a feel-good approach — anything of value from a cancer diagnosis. Ideally, Adam would discover in this process truths that non-stricken people would have yet to appreciate. It is presumptuous to speculate as to what those truths might be. A powerful script would be one that has begun to figure them out.

Fairly enough, “50/50” assigns cancer as a random curse. Certain forms are of course attributed to certain activities, such as smoking and tanning, but in this film we are presented with spinal cancer, lymphoma, prostate. There is rightly a “why me” element to “50/50” that is briefly presented without pity and without answers, and then chucked aside like the trash in Katherine’s car. We know certain behaviors are risky. We don’t usually know why some people get breast cancer or prostate cancer and others don’t. There is much we can do to improve our general fitness, but nothing — sadly — that will ward off what happened to Adam. At least that we know of.

There is a notion that human beings are all on borrowed time, so just take what you can get and try to make the most of it. “50/50” occasionally hints at this. In fact that is Rogen’s character. But this sentiment is routinely rejected by Adam. At one point he tells Katherine that he is “starting to realize I’m probably gonna die.” Yet he is uninterested in celebrating the present unless/until he knows he will clear this staggering hurdle.

A strongly implicit statement is made here about religion. Adam has none, nor do his acquaintances. This is a completely secular struggle. In the hands of a faith-driven filmmaker, there would be immense prayer, probably some form of repentance. Very implicitly, “50/50” perhaps makes viewers wonder about the differences between hope and prayer.

The most cynical view of the film, which might be valid, is that it recommends the most retail of solutions to even life’s most pressing problems. If you’re sick, you go to a hospital and let them deal with it. If you need a girl, you go to a bar or a bookstore or an art exhibition. If you need comfort, you call Mom. If you need a friend, get a dog.

In one of the film’s stronger messages, Adam ultimately realizes that others are more concerned about his condition than he previously thought. However, these scenes are punchless. In one he finds a cancer-support book Kyle has been reading, and in the other, he hears his mother tell a doctor that the “highlight of my week is this cancer support group,” which would be far more powerful if she were actually shown attending.

It’s worth suggesting that “50/50” is a movie about the difficulties of young men finding the right woman. On this score, Kyle is no better off in the end. Adam is sort of getting there ... maybe ... after a very slow start.

“I’ve never been to f-----’ Canada,” Adam reveals, before acknowledging what can be one of life’s most powerful aspirations. “I’ve never ... told a girl I loved her.”

That’s within the realm of possibility now, though he ultimately will tell Katherine at a moment of despair, “I wish you were my girlfriend.” Adam’s not quite ready for the “L” word yet. Like the title, he is halfway there.

2.5 stars

(May 2013)

“50/50” (2011)

Starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Adam ♦

Seth Rogen as Kyle ♦

Anna Kendrick as Katherine ♦

Bryce Dallas Howard as Rachael ♦

Anjelica Huston as Diane ♦

Serge Houde as Richard ♦

Andrew Airlie as Dr. Ross ♦

Matt Frewer as Mitch ♦

Philip Baker Hall as Alan ♦

Donna Yamamoto as Dr. Walderson ♦

Sugar Lyn Beard as Susan ♦

Yee Jee Tso as Dr. Lee ♦

Sarah Smyth as Jenny ♦

Peter Kelamis as Phil ♦

Jessica Parker Kennedy as Jackie ♦

Daniel Bacon as Dr. Phillips ♦

P. Lynn Johnson as Bernie ♦

Laura Bertram as Claire ♦

Matty Finochio as Ted ♦

Luisa D’Oliveira as Agabelle Loogenburgen ♦

Veena Sood as Nurse Stewart ♦

Jason Vaisvila as Cute Guy with Dreads ♦

Brent Sheppard as Minister ♦

Marie Avgeropoulos as Allison ♦

Adrian McMorran as Bartender ♦

Stephanie Belding as Friendly Nurse ♦

Andrea Brooks as Attractive Woman #2 ♦

Ryan W. Smith as Joe ♦

Karen van Blankenstein as Nurse Scott ♦

William ‘Bigsleeps’ Stewart as George ♦

Bonnie Bollivar as Elderly Female Chemo Patient ♦

Beatrice Ilg as Pretty Girl ♦

Chilton Crane as Mother on the Bus ♦

Amitai Marmorstein as Young Person on the Bus ♦

Lauren A. Miller as Bodie ♦

Will Reiser as Greg ♦

Richard C. Burton as Thom the Patient ♦

Neil Corbett as Hospital Tech ♦

Karolina Sabat as Art Gallery Patron ♦

Christopher De Schuster as Art Gallery Patron ♦

Susan McLellan as Bar Girl ♦

Marlow the Wonderdog as Himself ♦

Denver as Skeletor ♦

William as Skeletor ♦

Stephen Colbert as Himself (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

D.C. Douglas as Live Volcano Reporter (voice) (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

Tom MacNeill as Office Staff (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

Kiwi O’Gorman as Barista #2 (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

Cameron K. Smith as Chemo Patient (uncredited per IMDB)

Directed by: Jonathan Levine

Written by: Will Reiser

Co-producer: Nicole Brown

Co-producer: Kelli Konop

Co-producer: Tendo Nagenda

Line producer: Shawn Williamson

Executive producer: Nathan Kahane

Executive producer: Will Reiser

Producer: Evan Goldberg

Producer: Ben Karlin

Producer: Seth Rogen

Associate producer: James Weaver

Associate producer: Ariel Shaffir

Associate producer: Kyle Hunter

Casting: Francine Maisler

Original music: Michael Giacchino

Cinematography: Terry Stacey

Editing: Zene Baker

Production design: Annie Spitz

Art direction: Ross Dempster

Set decoration: Shane Vieau

Costume design: Carla Hetland

Makeup and hair: Monica Huppert, Sanna Seppanen, Debra Wiebe, Michelle Hrescak, Tanya Hudson, Andrea Simpson, Marine Wong, Céline Godeau

Post-production supervisor: Nancy Kirhoffer

Unit production manager: Paul Lukaitis

Stunts: Scott Ateah, Ed Anders, Brett Armstrong, Dan Redford, Owen Walstrom

Special thanks: Uwe Boll, James L. Brooks, Dr. Todd Carpenter, Kayla Cox, Laura Kittrell, Ira Levine, Judi Levine, Laura Mattingly, James McAvoy, Jacob Nathan, Jen Zaborowski