‘The Breakfast Club’: Any

24-year-old in high school

is bound to get into trouble

The chief accomplishment of John Hughes’ “The Breakfast Club” — other than its enormous return on investment — is illustrating how much our schools are like prisons. Maybe that should be troubling. Even those with 1,600 SAT scores are treated like inmates. You have to be there. You can’t leave (until they tell you to go). There’s a warden. There’s virtually no due process. You must ask permission to speak. There’s little to no TV. For entertainment, you get a library. You might clash with fellow inmates in the mess hall. The showers are a risky place. You don’t get a vote. And everyone has to know what everyone else did to get in here.

Welcome to conformity.

“The Breakfast Club” isn’t here to question formal education. It’s here to get something off teenagers’ chests. That can work at the box office. In a departure from the likes of “Mean Girls,” “My Bodyguard,” “Heathers” and others, the grievances of “Club” are not directed at fellow students, but grownups. At least any grownup in position of authority. Three of the students featured in “Club” are what society considers high achievers. No matter. Their parents are ruining their lives!

OK, the purists will say it’s much more than that. It’s showing young people tearing down those artificial walls that separate us into cliques and outcasts. If the movie were really doing that, it would be quite the public service.

It never seems to occur to the sadistic vice principal/warden/NurseRatched, Mr. Richard Vernon, that he would extract far more punishment, and get far better results from his assignment, simply by ordering the students to separate rooms. In fact, it’s kind of curious that none of the students points this out to him. If that’s not doable, at least Vernon could actually sit in the same room that the students are in to prevent things from getting out of hand. He doesn’t want to. See, he’s a prisoner here too.

“The Breakfast Club” is making far less of a statement about cliques than about boredom, maybe the most curious of life’s perils. Most people dread it even worse than getting a disease. And that’s a big risk for Hughes. If the characters are getting bored here, maybe the audience will too? Gene Siskel bluntly questions whether “today’s young audience” will “sit still for a film that’s virtually all talk?” (Well, it’s not all talk. Each student, like something out of “Fame,” gets his/her own dance. There’s a lot of jumping over railings, counters and bookcases. Forget wrestling — it’s practically a gymnastics meet.) Siskel’s probably right that it’s a tougher sell for teens. But strangers conversing is still happening today, such as in “Daddio.”

Perhaps we’re aware that boredom, like alcohol and obnoxious acquaintances, brings out the worst in us. Human beings came of age constantly foraging for food and shelter. Now that we’ve got those things in spades, we need other interests to pass the time. Entertainment. Trophies. Cool friends. Great hair. Good grades. When we’re interrupted from those pursuits, that’s when we’re inclined to do something stupid.

None of the characters expresses any alarm about missing something important on this day — work, practice or a family event. They seem to think that by doing about seven hours of time, they’re getting screwed. It seems like they’re getting off lightly for their transgressions, at least some of them. Sit in a room and write 1,000 words, and this won’t hover over graduation.

The John Hughes canon is either the answer to, or bookend of, the biggest teen-movie sensation of the early 1980s — raunch. “Porky’s,” a massive and unexpected box office hit that spawned a subgenre, dismayed critics with its perceived misogyny and peeping toms and maybe mostly with the amount of people who bought a ticket to see it. “The Breakfast Club” takes a different approach, not immediately, but four years later. In a group interview (there were several of those) published in the Chicago Tribune on Feb. 17, “Breakfast Club” cast members are unanimous in denouncing the “Porky’s”-like treatment. “Mindless garbage,” Estevez says, with “nothing to offer.” Sheedy says “They’re very exploitive,” and Nelson observes, “A lot of them treat teenagers as if they’re animals.” But “The Breakfast Club” isn’t fully immune from dubious sight gags — there’s a scene where Bender finds himself under a table.

Anyone watching “The Breakfast Club” now for the first time is bound to notice that this particular film couldn’t be made today. The three-letter word beginning with “F” is shown in the opening scenes, and the longer version of that word is shouted early in the film. It’s not just that word. One student mentions bringing a firearm to school. There is casual bullying and casual references to bullying. When Andrew does a dance, we even see a partial Confederate flag in the library. (It’s evidently the 1980s Georgia state flag.) It’s “a very white movie,” writes Pauline Kael.

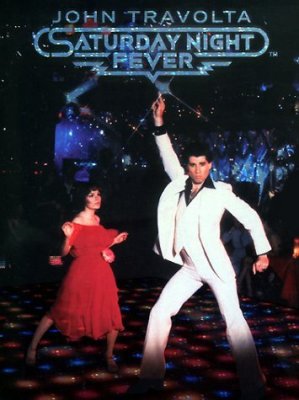

All of that is important to pop culture historians. But none of it is a deal-breaker. It would be difficult for a movie to offend as much as “Saturday Night Fever”; it’s still rightly regarded as a classic.

Hughes introduces the movie with the famous Simple Minds song — really, because of that song, it must be among the top 10 or so greatest movie openings. That hint of a great soundtrack isn’t realized. Hughes adds a voiceover from a student that is, like Serpico being wheeled into the hospital, a flash of the ending of the movie. In “Serpico,” it works mightily well. It brings a jolt of high drama to the opening scenes. Were the story beginning chronologically, it would take a while to get that kind of impact as we first learn about the idealistic young Frank. In “The Breakfast Club,” this approach is a misfire. It only successfully foreshadows that we’re going to be told, and not shown, everything. The timeline is one day at school, not a career on the police force. We get a description of five people we haven’t met yet: “A brain, an athlete, a basket case, a princess, a criminal.” We don’t need hints about how it will end. We haven’t even met these characters yet and have no idea whom this statement is addressed to. It is forcing instant homework upon the viewer, too many details that the viewer will quickly learn anyway.

Another part of the opening works very well, when the kids drive up to the school. We see the cars and the heavies — er, the parents — and get an introduction to the students’ insecurities. Claire’s dad assures that skipping school to go shopping isn’t a career-ender; she might be a bit spoiled. Anthony is ordered by his mother to find a way to study on this day. Dad blames Andrew for getting caught and potentially losing a scholarship as a “discipline case.” Allison is given the cold-shoulder by her ride. Depicting high school students with parents in real time is a far stronger approach than, say, in “Broadcast News,” where the movie opens with portrayals of what the three stars were like as children. In “Club,” the behavior of three parents in the cars will reinforce the testimony provided throughout the movie that it’s the grownups who are ruining these kids’ lives and are responsible for any kind of acting out. Might a psychologist argue that each of the kids has broken rules to garner attention? Several of them, yes, but not all.

As the students take their seats, Hughes provides some delicious fodder for arthouse directors, who would be less keen on the endless dialogue of Bender and far more interested in the visuals of the seating chart. None of these students are friends with each other, and there is ample space for everyone to have their own table. Yet the first four students attempt to sit close to each other. We first see the room with Claire in the front row; presumably she took her seat first. Brian is directly behind her. Andrew approaches and asks Claire if he can sit at the same desk; she agrees. Bender approaches and bullies Brian out of the second desk. The last person, Allison, sits as far from the others as possible. There is undoubtedly a parallel here to the typical school cafeteria — the ultimate seating battleground.

By the 16th minute, the movie is virtually complete. That’s when the crucial decision is made by the other students to side with Bender over Vernon. It’s not unlike “American Graffiti,” in which Curt has to decide whether to cover for his thug acquaintances or report them to the adults. Why do the “Club” kids protect Bender? He has only belittled or bullied them thus far. They do think, evidenced by snickers over his Barry Manilow comment, that Bender is funny. Perhaps the intensity of Vernon’s reaction alarms them. They do not seem afraid of Bender, but they could be afraid of being seen “tattling.” Or they may wish they had done what Bender did. Or they may be amused as to how this whodunit plays out. Whatever the reason, at this point, we have all we need. We know who are the bullies, the cynics, the rebels.

But not totally rebellious. Everyone shows up on time. Hughes’ biggest mistake is not having Bender walk in late. For a few minutes, we’d see the others silently accepting their boredom and beginning to write their assignment. Then Bender would stroll in, receive another detention for being late, and also sit down quietly. Eventually, one of the curious other students would ask him a question, and then the rest of the movie can get underway.

Were the adult in the room just a normal adult, the rest of the students probably would’ve turned on Bender immediately. Mr. Vernon is every bit the bully as Bender and only slightly more likable than notorious movie villains Brad Wesley and Hans Gruber. He orders the kids not to talk and not to move, and he tells them to “Shut up.” Hughes resorts to a cheap movie line, giving Vernon the first name of Richard, so his antagonists can call him “Dick,” something that really fascinates people born after 1970.

Bender is asked by Vernon if the instructions are clear; Bender replies, “Crystal,” years before Jack Nicholson will famously say the same word in “A Few Good Men.” That’s one of the good lines. But the movie isn’t funny enough. In his review, Gene Siskel writes that “you’ll still wince once or twice when the actors seem to be reciting set speeches rather than overlapping dialogue.” Claire tells Bender at one point, “Only burners like you get high,” a statement no one in this setting possibly believes.

It’s March, we’re told by voiceover (another needless detail to clog the mind), and all the students, as their ordeal begins, are still wearing their jackets in the library. Maybe they plan to leave soon? The movie was shot at the old Maine North High School in Des Plaines, Ill., and the actual school library was too small for the movie’s needs, so the filmmakers created a bigger one in the gymnasium. But the one we see is too big for a school — as if the delinquents are at the New York Public Library — and it makes the school appear far more lavish than one would think from the brutalist-style exterior and hallways.

Normally, people like Andrew and Claire wouldn’t be conversing with people like Bender. “The Breakfast Club” is a warning about engaging verbally with fellow human beings who may be hostile. You might receive questions in front of other people that you’d rather not answer. Seriously rather not answer. “You couldn’t ignore me if you tried,” Bender informs the group. Why is he so adept at embarrassing people? He’s happy to get in trouble. He has, at least according to this picture, nothing to lose. You might think you can handle anything he’s got. There would be, actually, in real life, ways to fire back and get under his skin, for anyone so inclined. But he’s a pro at this. He’s got an answer for everything and has deflected the kinds of admonitions he receives here countless times. Bender wants to probe these people for the same reason Andrew would love to wrestle them — it’s probably an easy win.

The students in “Club” have widely different scorecards, but the one that seems most important to all, like in many teen movies, is sex. Hughes quickly has his characters indulge in these uncomfortable questions. That’s despite the fact that Hughes insisted to Gene Siskel that his film plays it down; “a lot of kids are very conservative about sex.” The boasting in this film and others has everything to do with quantity and nothing to do with quality. It’s either the amount or the variety. To “win” one of these conversations, you either have to mention the amount of times, or the unusual locations, or successful techniques. What people in these conversations want to hear from others is not tips and insight but a lack of activity. An experience with the prom queen may feel great, but not if someone else tells of three such experiences. Underlying the drama is the strong chance that any or all of the speakers might be lying, or at least exaggerating. It’s like a poker pot. You generally don’t want to go all-in. The “Club” characters could not care less if someone else in this group is a better student or can run faster, but boy, if the way the others talk makes me feel like I’m behind on sexual progress, there is no hope for me. However it may heal teen relationships in other ways, “The Breakfast Club” has no cure for this kind of stigma.

Because it is a caustic examination of stereotypes, “The Breakfast Club” does not include a staple of the teen ensemble, the Archie Andrews/Richie Cunningham/Brandon Walsh centrist, the kid who’s maybe not the coolest or funniest or most talented of the group but is its most respected and de facto leader. Without such a character in “Club,” it’s Judd Nelson’s movie.

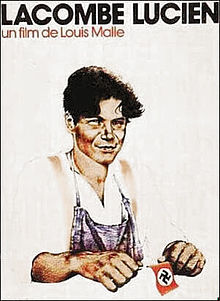

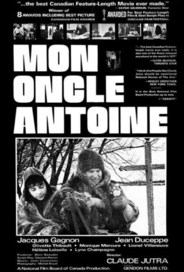

Nelson is too old for this film — he was apparently 24 during filming and, upon its release, 25. So was Richard Dreyfuss in “Graffiti.” Using older actors to play teens is common. Gabrielle Carteris was pushing 30 in “90210.” Hughes has a tough choice here between authenticity and the star system. Sometimes, unknown young people who seem in the moment get plucked off the street for landmark roles (“Zabriskie Point,” “Lacombe, Lucien,” “Mon Oncle Antoine”). But casting calls for movies like “The Breakfast Club” or “Fast Times” or “Taps” or “The Outsiders” can be like the NFL Draft — some of these young people are bound to be superstars, but no one knows yet exactly who (think Paul LeMat getting a bigger part than Harrison Ford) — and none of them have any leverage; all will happily take the job. For a director, playing God in this world of pop culture has to be mighty appealing. Hughes went this route, as most would, rather than observing non-Hollywood kids at a school and offering them jobs. His cast is talented and experienced but collectively too old for this assignment.

The “Club” actors, at least two of them, are associated with the “Brat Pack,” a term that probably deserves its own essay and is used here only grudgingly. It was coined by New York magazine writer David Blum after the release of “The Breakfast Club.” It refers to at least some of the actors in “Club” as well as some in “St. Elmo’s Fire.” Why their agents thought it was a good idea to invite a writer to join them at the Hard Rock Cafe in 1985 is a head-scratcher. The article indicates a little bit — a little bit — of preferential treatment that was indulged. It seems pretty innocuous, such as skipping the line at a nightclub or being let in for free to see a movie that probably cost about $3. The biggest stretch is the article’s justification that any of these actors in the mid-1980s had anything remotely like the presence of the Rat Pack a couple of decades earlier.

It’s not appealing to be called a “brat,” especially when undeserved, and the actors denounced the article and, apparently, stopped hanging out together. Were they really any different than young stars of the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s? Probably not. But the early-to-mid-1980s is probably the most famous era in the category of Young Movie Star Discoveries and Famous Teenage Movies. These 20somethings probably shouldn’t have been inviting writers to go clubbing while their movie about conscientious teenagers was still playing in theaters. There is some irony that the actors in “Club,” and not those of “Porky’s” or “The Hollywood Knights,” are called “brats.” The name has stuck to this day. (If you wonder why movie stars don’t trust writers.)

Rather than coming across as a north suburban Chicago teenage “burner” (a term used in the film), Nelson looks and sounds like a trained grownup actor. He is far too articulate for this character and never shuts up; he’s more gossip girl than brooding malcontent. He is nearly eight years older than Anthony Michael Hall, which makes the bullying easy. Notice how much more Dreyfuss accomplishes in “Graffiti” — he’s funny and conflicted and has a goal. (He’s also, unlike Nelson, an oftentimes Oscar nominee.)

“Club” does have the jock, a character not as common as it may seem in teen movies. There isn’t one in “American Graffiti,” “Risky Business,” and “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” (unless you count a few scenes with Forest Whitaker). Emilio Estevez was 22 at the film’s release. He looks athletic but perhaps not state-champion athletic, and he carries himself with probably a bit more confidence than a real person would in these confrontations with Bender. Ideally he should come across as able to handle Bender if needed but not really wanting to mix with him; Bender is bigger. Because Estevez is not called upon to set the tone as Nelson is, he anchors the production and keeps the ludicrousness from being even more ludicrous.

John Hughes on the set of “The Breakfast Club.”

In a group interview (there were several of those) published in the Chicago Tribune on Feb. 17, 1985, Nelson says the movie “has a lot to do with the fact that nothing is what it seems ... they have a lot more in common than they’d anticipated ... by the end of the day, they’ve gotten a lot of new information.” Estevez says, “Everyone grows and everyone comes to terms with the problems that’re inside of them.” Ally Sheedy offers, “It's about five kids being completely honest with each other. And there’s no superficiality about them.” Estevez says “Club” is “more like health food” in an era of movies such as “Tough Turf” and “Hot Moves.” Gene Siskel calls it a “thoroughly serious teenage version of ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’ ”

In real life, a generation is about 15-20 years. For high school, it’s maybe barely five. You enter as a freshman, and five years later, no students who were at that school when you were a freshman will still be there.

But many of the grownups will be. They’ve seen it all. Again and again. To them, movies like “The Breakfast Club” might be their own “American Graffiti” or even “Rebel Without a Cause.” Which all brings to mind whether, at the time of its release, anyone over 20 cared about “The Breakfast Club.” With an R rating, it’s probably cutting off a large potential audience. On the other hand, those 13-and-up who were interested likely saw it anyway. (Roger Ebert writes that PG-13 “would have been more reasonable.”) The movie struck a chord with a select young demographic that idolizes it as well as its close relative “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.” That fandom is vocal enough to make you think “The Breakfast Club” maybe had more presence than it actually did. It finished 13th in the year’s box office with a $48 million gross. It did beat “St. Elmo’s Fire” that year. But it lagged “The Goonies” and got thumped by “Cocoon,” a movie about old people.

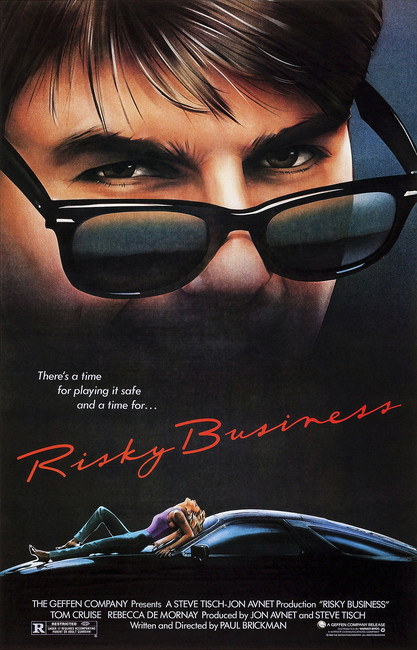

Against other early-’80s teen hits, “Club” did beat the 1982 gross of “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,“ according to Box Office Mojo. But it’s not close to “Risky Business” or “Ferris” and was virtually doubled by “Footloose.” And blown away by “Porky’s.”

Hold on. Those other films all had budgets of $5 million or more. “The Breakfast Club” merely spent $1 million. As a work of art, it is a moderate success. As a business opportunity, it’s a Hall of Famer.

An interview with the cast of “The Breakfast Club” in Los Angeles,

published in the Feb. 17, 1985, Chicago Tribune

The price of Hollywood production is very much in the news today. Filming his movie in a shuttered suburban Chicago high school, Hughes may have been simply resourceful, or he may have been way ahead of his time, in the category of Cost Controls. “Club,” like “Graffiti” and “Risky Business,” was not filmed on more expensive Hollywood sets, and all three featured young actors who hadn’t yet hit the big payday. If you’re avoiding huge star salaries and numerous expensive locations, you probably have a good chance of getting your film made (and making money — for somebody).

In a February 1985 Chicago Tribune interview by Gene Siskel, Hughes credited producer Ned Tanen for reading the script and getting it made as a film. Hughes said that “a lot of people” thought “Club” would be a “wonderful play but not a movie.” The bottom line shows Hughes and Tanen were enormously correct, but not necessarily for artistic reasons. Teenagers go to movies. They don’t go to plays.

Siskel writes that Hughes “lives and works” in the northern Chicago suburb of Northbrook. Hughes spoke negatively of Hollywood, though much of his later “Ferris Bueller” is filmed there. For “Club,” Hughes may have admired the old Maine North High School and its brutalist architecture as capturing the mood he wanted, or it may have just been his best and easiest offer, an actual high school building closed three years earlier not far from his Northbrook base. Hughes attended high school during the height of Vietnam. “Club” does blame adults for everything. But otherwise, it is completely detached from the Vietnam era and is solidly ’80s with yuppie references, sushi for lunch, a makeover for a girl, a little unlike the sitcom “Family Ties” in which the Keaton parents regularly contrasted their ’60s sentiments with Alex’s materialism in hopes of drawing a young and old audience. “Club” needs no grownups.

Hughes told Gene Siskel that the name “The Breakfast Club” came from the son of a friend. It was supposedly the nickname for morning detention at New Trier High School, which, like Hughes’ own Glenbrook North, is a wealthy high school in Chicago’s northern suburbs. Claire is portrayed as wealthy, but the other four students are far more middle class than, say, those in “Ordinary People.” What is Hughes’ end game? He might be sending dual messages: 1) Don’t judge a book by its cover, and 2) Your actions may have bigger consequences than you think.

The movie’s signature moment is not Bender’s closing fist-pump but brilliant Brian’s observation-question that they’re all friends right at the moment and would they still be friends on Monday in the school hallways. Claire unnecessarily tries to answer. Let Brian and everyone else, for one day, indulge in a little fantasy. They already graduated in Reality.

3 stars

(May 2025)

“The Breakfast Club” (1985)

Starring

Emilio Estevez as

Andrew Clark ♦

Paul Gleason as

Richard Vernon ♦

Anthony Michael Hall as

Brian Johnson ♦

John Kapelos as

Carl ♦

Judd Nelson as

John Bender ♦

Molly Ringwald as

Claire Standish ♦

Ally Sheedy as

Allison Reynolds ♦

Perry Crawford as

Allison’s Father ♦

Mary Christian as

Brian’s Sister ♦

Ron Dean as

Andy’s Father ♦

Tim Gamble as

Claire’s Father ♦

Fran Gargano as

Allison’s Mom ♦

Mercedes Hall as

Brian’s Mom ♦

John Hughes as

Brian’s Father (uncredited)

Directed by: John Hughes

Written by: John Hughes

Producer: John Hughes

Producer: Ned Tanen

Co-producer: Michelle Manning

Executive producer: Gil Friesen

Executive producer: Andrew Meyer

Music: Keith Forsey

Cinematography: Thomas Del Ruth

Editor: Dede Allen

Casting: Jackie Burch

Production design: John W. Corso

Set decoration: Jennifer Polito

Costumes: Marilyn Vance

Makeup and hair: Linle White, Robyn Goldman, Ron Walters

Executive in charge of production: Adam Fields

Production supervisor: Richard Hashimoto

Unit production manager: John C. Chulay

Thanks: Marlene Alexander

Thanks: Bobby Richter

Thanks: Don Stillwell

Special thanks: David Bowie