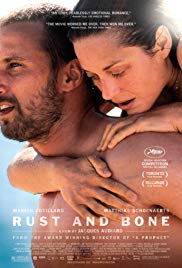

‘Rust and Bone’ heals a meaningless life, one step at a time

The important decision in “Rust and Bone” takes place outside an apartment. Stéphanie is about to chalk up this evening as another forgettable night. Ali asks to extend it. First, she says no. There’s someone else in the apartment, she says, and that’s maybe not that hard to believe but sounds like an obvious excuse. Ali persists.

Many movies put a man outside a woman’s door. Usually one of the two characters wants him to come in; the other is not so sure. In “Rust and Bone,” this is one of two essential sequences treated as cliché. Stéphanie is motivated to say yes. Is she interested in him, is she merely thanking him for the ride, or does she want to see how her boyfriend reacts? And if her boyfriend does love her, how should he react to this event? Her decision sets up a very creative scene in which Ali, a bouncer, encounters Stéphanie’s boyfriend, a disagreeable fellow. Had the boyfriend simply said “How are you doing, anything we can do for you,” then Ali probably quietly leaves. What emerges is a psychological duel in which the winner will be the one to get the call from Stéphanie. Ali has told Stéphanie she dresses like a prostitute. Why is she still interested? Perhaps because he noticed, and her boyfriend never did.

“Rust and Bone” is about physicality, but even more, it’s a story of offers. We take the best ones we get, and it doesn’t always occur to us that with a little effort, we might be able to get something better.

Disability is a popular movie theme. That it clutches our emotions and comes up big at the Academy Awards are at least two powerful reasons why elite filmmakers might explore it. “Rust” can count among its cousins “The Best Years of Our Lives,” “Coming Home” and “Million Dollar Baby.” And even “Notting Hill.” Notice that it tends to be robust, physical elites experiencing the disability.

Pity. It’s an extremely powerful emotion but not a desirable one. Bernie Madoff supposedly committed his massive fraud because he was once pitied and vowed it would never happen again. The bad guys in movies are not supposed to evoke sympathy. But the heroes aren’t either; if they’re going to be heroes, then we admire them, not pity them.

“Pitiful” is a common term but typically used in conversation as a slur, at odds with its primary meaning. “Rust and Bone” quietly reminds us that there are in fact very few people we actually pity in the world, and most of them are people who have suffered traumatic accidents. All kinds of people have lost close family members, or their job, or their lover, through no fault of their own, but emotional loss happens often enough that observers’ patience for it is limited, we presume eventually people can recover, and we become frustrated when they don’t. On the other hand, if you’ve lost a body part or some of your brain function, many would say that’s something different.

It would be interesting if “Rust and Bone” and its magnificent star, Marion Cotillard, had more to tell us about this topic, and surely they do, but as with the apartment invite, the obvious scene is treated only as an obligatory cliché, almost schlock. A man hits on Stéphanie at a bar, she’s flattered, then he notices her lack of legs and makes the mistake of apologizing, and a violent scrape ensues.

Entertain this analogy: Nearly all women gush when told by a stranger that they’re beautiful. A tiny handful, including Cotillard, have surely heard it so often, it can’t be more than an annoyance, from someone they now have to thank for something they’ve already got too much of. Cary Grant used to lament that in real life, he’s not Cary Grant either.

Perhaps “Rust” is implying that pity, like complimenting a stranger’s beauty, is indeed helpful in small doses. Stéphanie could use more support from her colleagues, family members and others in the amputee community than she receives. Has she resisted them? Perhaps. Ali assists her, but he never judges her on her disability, only availability.

“Rust” aims to measure the impact of physicality on our lives. We see two people who can handle beasts because of their physical strength and skill, a pair who have failed to connect with other human beings on a much more emotional, practical level. One of them will begin to do so; the other will take a longer learning curve.

Cotillard’s co-star, Matthias Schoenaerts, is the brute who should have to convince everyone that he is not a pathologically violent person but doesn’t. He is raising a boy but more often acts the child. Curiously, Cotillard is the star, but this is Ali’s story. She’s here, as is Jo in “A Few Good Men,” to get the man to a better place, a place that has something to do with quality parenting. Ali is amiable. People prone to his level of violence who would either be jailed or heavily sued in real life are easily cured in movies, whether it’s “Good Will Hunting,” “Road House,” even 2018’s genteel “Green Book.” Ali, formally Alain, can be rough or negligent with his son, busy with work or sex, summoned to an “OP,” and there’s still always someone available to take care of the boy. On the plus side, “Rust” resists the temptation to have Ali scammed at the fight club.

The director, Jacques Audiard, wants skin and blood. He lets his camera hover and jiggle as close to the action as possible. That stark approach is common, but what “Rust” seems to be missing is pain. Characters get maimed yet never scream out for Vicodin or even alcohol. Roger Ebert, in a 4-star review that is one of the last he ever filed, writes that acknowledgment of what has happened is perhaps the most traumatic part of the ordeal. Ebert says Audiard “is interested in what remains of people after something has been lost.” The French title is the same as the English version, “De rouille et d’os.” The meaning is said to refer to the feeling in the mouth of taking a hard punch.

Audiard, apparently coincidentally, created a film in the crosshairs of social controversy. A year before filming began, an American SeaWorld trainer, Dawn Brancheau, was killed by an orca. SeaWorld has been under siege ever since. The use of whales as marine-park attractions had long been a target of animal-rights groups. “Rust” passes no judgment on Stéphanie’s profession. Apparently the nature of the whale accident was changed by filmmakers to avoid similarities to Brancheau’s tragedy, but it’s very much the same concept. Stéphanie seems to view her profession as similar to driving a forklift. She appears to derive no joy or comfort from animals in her private life, nor do her colleagues rally around her. It would seem she could easily resume a career dealing with animals if she so chooses; by the ending, she somehow appears happier as a “Fight Club” accountant.

“Rust” introduces us to characters in need of a bottom. It gets off the mat implying that the end game is sex, that as long as you’re getting some, life is functional. Stéphanie and Ali are not the most likable people. It will take considerable discomfort for them to realize how much they have going for themselves, and that’s “have,” in present tense.

3 stars

(January 2019)

“Rust and Bone” (2012)

Starring Marion Cotillard

as Stéphanie

♦

Matthias Schoenaerts

as Alain van Versch

♦

Armand Verdure

as Sam

♦

Céline Sallette

as Louise ♦

Corinne Masiero

as Anna ♦

Bouli Lanners

as Martial ♦

Jean-Michel Correia

as Richard ♦

Yannick Choirat

as Simon ♦

Mourad Frarema

as Foued ♦

Fred Menut

as Le patron d’ELP Sécurité ♦

Duncan Versteegh

as Soigneur d’orques ♦

Katia Chaperon

as Soigneuse d’orques ♦

Catherine Fa

as Soigneuse d’orques ♦

Andès Lopez Jabois

as Soigneur d’orques ♦

Océane Cartia

as La baby-sitter ♦

Françoise Michaud

as La mère de Stéphanie ♦

Irina Coito

as La prof d’aérobic ♦

David Billaud

as Le maître-chien ♦

Yvon L’Allain

as Le prothésiste ♦

Fabien Baïardi

as Le dragueur dans la boîte ♦

Laetitia Malbranque

as La femme du supermarché ♦

Soulyane Rajraji

as Le délégué syndical du supermarché ♦

Pascal Rozand

as Le concessionnaire ♦

Hedi Touihri

as Le chef sécurité du supermarché ♦

Martine Millar

as La collègue d’Anna ♦

Anne-Marie Tomat

as L’infirmière de l’hôpital près du lac

Directed by: Jacques Audiard

Written by: Jacques Audiard (screenplay)

Written by: Thomas Bidegain (screenplay)

Written by: Craig Davidson (story)

Producer: Jacques Audiard

Producer: Martine Cassinelli

Producer: Pascal Caucheteux

Line producer: Antonin Dedet

Co-producer: Jean-Pierre Dardenne

Co-producer: Luc Dardenne

Co-producer: Annemie Degryse

Co-producer: Alix Raynaud

Music: Alexandre Desplat

Cinematography: Stéphane Fontaine

Editing: Juliette Welfling

Casting: Mohamed Belhamar, Richard Rousseau

Production design: Michel Barthélémy

Art direction: Yann Megard

Set decoration: Boris Piot

Costume design: Virginie Montel

Makeup and hair: Myriam Roger, Frédérique Ney, Pascal Larue, Emmanuel Pitois, Alice Robert, Catherine Ichou

Stunts: Olivier Schneider, Yves Girard, Patrick Vo, Eddy Benguedih, Serge Crozon-Cazin, Mathieu Dubois, Clément Huet, Ibrahima Keita,

Jean-François Lenogue, Gregory Loffredo, Alex Martin, Ilya Nikitenko, Louis-Marie Nyee, Eric Tatin, Sébastien Vandenberghe, Jean-Jacques Domingues, Laurent Mulot, Santi Sudaros