‘Mon Oncle Antoine’ — When a Merry Christmas in Quebec was wishful thinking

Life sure is grim in “Mon Oncle Antoine.”

Mining jobs bring early deaths and desecrate the environment. Funeral arrangements are tacky to the point of insulting. Your boss might be a drunkard. Your co-workers may be incompetent. Transportation is no better than 100 years ago. A spouse might leave home for months because he’s fed up — not with his wife, but his job. A dad might see his daughter as nothing more than a stream of income. Healthy teenagers can get sick and die at a moment’s notice. And, in general, it looks like it tends to be cold up here.

Yet, “Mon Oncle Antoine” boasts a pioneer spirit that elevates it from black comedy to the short list of Canada’s most beloved films. There’s something to believe in, even if the unmistakable message to the young protagonist is Get out of here.

“Antoine,” the work of Canadian auteur Claude Jutra, was made in 1970, a time in Canada that Roger Ebert called “the height of Quebec separatism.” It suggests in its opening scene that there is labor tension. What are the issues? Apparently something to do with the motor vehicle pool and a lack of respect from “The English” who run the place. And that working in an asbestos mine (yes, the concept alone is horrifying) is too dangerous for anyone, at least under this kind of management, although only one character seems to believe this.

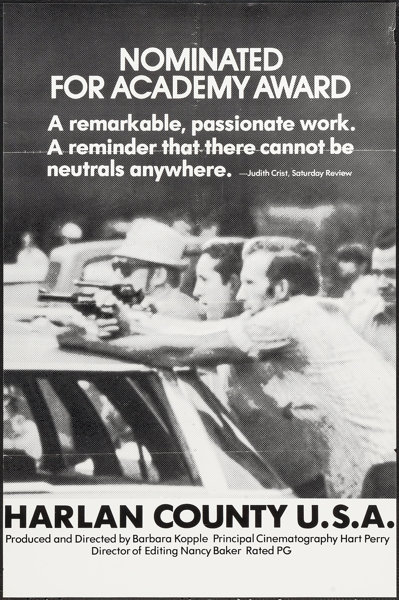

But before that “Harlan County U.S.A.” approach goes anywhere, “Antoine” pivots abruptly into a typical coming-of-age story. Here, the boy, Benoit, a teenager, is so young, and the time frame is so condensed, that the payoff of his revelation is minimal. It’s hard to believe that everything he witnesses in the two days before Christmas hasn’t already been experienced by him, maybe more than once. The villain, which is basically “The English” or anyone who owns a mine, is far beyond the scope of the boy’s maturity.

“Antoine” is probably an early effort in a genre now freely called “dramedy.” Visually, it’s a cousin to “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” which was released the same year. People from the past in a snowy area, small remote town, in which specialties are almost nonexistent; when there’s a job to do, everyone kind of pitches in. There may be rivalries and feuds and infidelity, but everyone pulls together in the face of the outsiders coming to confiscate the natural resources.

Could “Antoine” be labeled a “Western”? Something about the term doesn’t fit. The script sidesteps a standard device that is often powerful and often cliché — the outsider coming to town and shaking things up. Everyone central to this film is already here. Benoit will instigate nothing, but react.

Robert Mitchum liked to dismiss acting, pointing out that if Rin Tin Tin is considered one of the biggest movie stars, “It can’t be too much of a trick.” “Antoine” demonstrates, as does “Lacombe, Lucien” and certain other films, that filmmakers can virtually literally hire someone off the street to carry a landmark film. (Or a non-landmark film, such as “Zabriskie Point.”)

In a feature about the making of “Antoine” provided by The Criterion Collection, Jutra says the boy playing Benoit, Jacques Gagnon, was picked up as a hitchhiker. Jutra thought that was the perfect background for the lead role because “I wanted him to be a natural,” he says. Jutra said he met Lyne Champagne, the actress playing the teen girl Carmen, at a restaurant in town. But, in an example of the film’s divided priorities and/or box-office necessities, Jutra gave adult roles to veteran Canadian actors including the married Lionel Villenueve and Hélène Loiselle and himself.

This mix reflects how Jutra likely saw his endeavor as a documentary-like work of fiction with detached elements of cinema verite, the idea being that the local actors and setting would provide the authenticity and the veterans would provide the acting chops and box-office assurances. Jutra recruited residents for the town scenes, though according to commentary from The Criterion Collection, they were “hostile” or “suspicious” of Jutra’s crew because they were apparently featured in an earlier film and didn’t like the result. The production of “Antoine” was a tough sell — it needed Canada’s National Film Board to fund the full $450,000.

No question, the politics of this film involve serious inside baseball, at least for non-Canadians. There is a Wikipedia page for the 1949 Quebec Asbestos strike, another for “The Quiet Revolution” and another for the “October Crisis,” a stark 1970 political kidnapping event that took place during the filming of “Antoine.” But cinematically, this is a typical coming-of-age story. And one with disheartening revelations. Canadians surely appreciate the times and the setting, but for non-Canadians, there’s too much backstory here to feel the full effect.

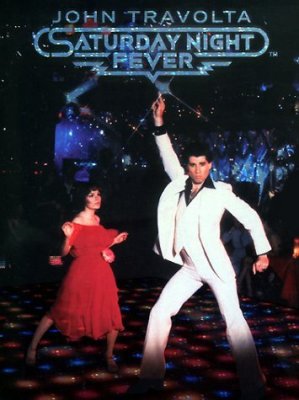

Geography is a major weapon of filmmakers. In “Saturday Night Fever,” Tony’s troubles are practically chalked up to the difference between Bay Ridge and Manhattan; the sooner he gets to the latter, the better off he is. “Antoine” suggests ambiguous, dueling sentiments for Benoit’s future — that the adults in his life offer nothing but reasons to leave, but with such a camaraderie that he can’t help but stay.

Snow often provides a robust man vs. nature story. It also attracts filmmakers in search of quirky people. It is notable that the characters of “Antoine” are right in the middle. They have a certain resilience, but they’re not Paul Bunyon; they’re capable of pranks, but they’re not the idiots of “Fargo.”

Visually, “Antoine” is enhanced by some beautiful scenes of the landscape and rank and file. We see asbestos spewing into the air, we see miners at a bar, we see people punching the clock.

However, some of the direction is uninspired, for example, an attractive woman who appears to be a semi-regular walks into the store, and everything stops as though she’s Rita Hayworth. Then two boys peek in on her trying on a corset; not only is it absurd to think she wouldn’t notice, but the scene is so predictable, it’s laborious. A fairly well developed character, Antoine, is reduced to airing his life’s grievances, which viewers should’ve come to have known by that point, through a dubiously timed speech when just some simple effort could easily fix their problem. Is it odd that a mother is calling this store for this service, rather than involving a doctor first, and then amid this moment serving the morticians dinner, on Christmas Eve?

It is probably unfortunate that “Mon Oncle Antoine” shares a similar title to a classic, Jacques Tati’s “Mon Oncle,” a 1950s work that won the Oscar for foreign film in the third year of the category’s existence as a competitive award. But that’s not the end of the name-dropping. There also is Alain Resnais’ “Mon oncle d’Amerique” of 1980. Both of those are France productions. All three “Oncle” titles landed on Ebert’s Great Movie portal.

Yet they have nothing else in common. “Mon Oncle” is a Monsieur Hulot comedy that warily looks forward, not backward. “Mon oncle d’Amerique” features a real, narrating philosopher, Henri Laborit, explaining with the help of lab rats why the characters in the melodrama are doing what they’re doing. Laborit would likely tell Benoit that the teen has the greatest cinematic attribute — youth — and to make a run for it while he still can.

3 stars

(June 2019)

“Mon Oncle Antoine” (1971)

Starring Jacques Gagnon

as Benoit ♦

Lyne Champagne

as Carmen ♦

Jean Duceppe

as Uncle Antoine ♦

Olivette Thibault

as Aunt Cécile ♦

Claude Jutra

as Fernand, Clerk ♦

Lionel Villeneuve

as Jos Poulin ♦

Hélène Loiselle

as Madame Poulin ♦

Mario Dubuc

as Poulin’s son ♦

Lise Brunelle

as Poulin’s daughter ♦

Alain Legendre

as Poulin’s son ♦

Robin Marcoux

as Poulin’s son ♦

Serge Evers

as Poulin’s son ♦

Monique Mercure

as Alexandrine ♦

Georges Alexander

as The Big Boss ♦

Rene Salvatore Catta

as The Vicar ♦

Jean Dubost

as The Foreman ♦

Benoît Marcoux

as Carmen’s Father ♦

Dominique Joly

as Maurice ♦

Lise Talbot

as The Fiancée ♦

Michel Talbot

as The Fiancé ♦

Siméon Dallaire

as A Customer ♦

Sidney Harris

as The Helper ♦

Roger Garand

as Euclide

Directed by: Claude Jutra

Written by: Claude Jutra (adaptation)

Written by: Clément Perron (story, adaptation)

Producer: Marc Beaudet

Cinematography: Michel Brault

Editing: Claire Boyer, Claude Jutra

Music: Jean Cousineau

Set decoration: Denis Boucher, Lawrence O’Brien

Makeup: Rene Demers, Suzanne Garand